List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East

It has been suggested that Patriarchs of the Church of the East be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2018. |

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

Main communions

|

Eastern liturgical rites

|

Major controversies

|

Other topics

|

|

The Patriarch of the Church of the East (Patriarch of Babylon or Patriarch of the East)[1] is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop (sometimes referred to as Catholicos or universal leader) of the Assyrian Church of the East. The position dates to the early centuries of Christianity within the Sassanid Empire, and the church has been known by a variety of names, including the Church of the East, Nestorian Church, the Persian Church, the Sassanid Church, or East Syrian.[2] In the 16th and 17th century the Church, by now restricted to its original Assyrian homeland in Upper Mesopotamia, experienced a series of splits, resulting in a series of competing patriarchs and lineages. Today, the three principal churches that emerged from these splits, the Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church, each have their own patriarch, the Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, the Patriarch of the Ancient Church of the East and the Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans, respectively.

Contents

1 History

2 Language

3 List of Catholicoi of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and Patriarchs of the East until 1552

3.1 Edessa era

3.2 Metropolitan of Seleucia-Ctesiphon elevated as titular Catholicos

3.3 Catholicos of the East with jurisdiction over Eastern provinces

4 After the Schism of 1552

4.1 List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East from 1552 to 1830

5 See also

6 References

7 Sources

8 External links

History

The geographic location of the patriarchate was first in the Persian capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in central Mesopotamia. In the 9th century the patriarchate moved to Baghdad and then through various cities in what was then Assyria (Assuristan/Athura) and is now northern Iraq, south east Turkey and northwest Iran, including, Tabriz, Mosul, and Maragheh on Lake Urmia. Following the Chaldean Catholic Church split from the Assyrian Church, the respective patriarchs of these churches continued to move around northern Iraq. In the 19th century, the patriarchate of the Assyrian Church of the East was in the village of Qudshanis in southeastern Turkey.[3] In the 20th century, the Assyrian patriarch went into exile, relocating to Chicago, Illinois, United States. Another patriarchate, which split off in the 1960s as the Ancient Church of the East, is in Baghdad.

The patriarchate of the Church of the East evolved from the position of the leader of the Christian community in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian capital. While Christianity had been introduced into Assyria then largely under the rule of the Parthian Empire in the first centuries AD, during the earliest period, leadership was unorganized and there was no established succession. In 280, Papa bar Aggai was consecrated as Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon by two visiting bishops, Akha d'abuh' of Arbela and Hai-Beël of Susa, thereby establishing the generally recognized succession.[4] Seleucia-Ctesiphon thus became its own episcopal see, and exerted some de facto control over the wider Persian Christian community. Papa's successors began to use the title of Catholicos, a Roman designation probably adopted due to its use by the Catholicos of Armenia, though at first it carried no formal recognition.[5] In 409 the Church of the East received state recognition from the Sassanid Emperor Yazdegerd I, and the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon was called, at which the church's hierarchy was formalized. Bishop Mar Isaac was the first to be officially styled Catholicos over all of the Christians in Persia. Over the next decades, the Catholicoi adopted the additional title of Patriarch, which eventually became the better known designation.[6]

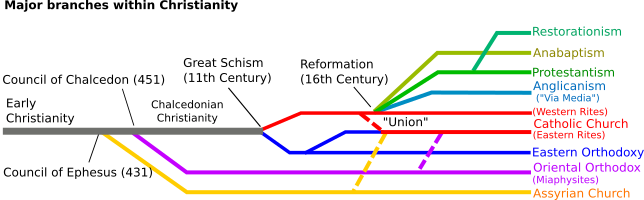

In the 16th century, another schism separated the church, with those following "Nestorianism" separating from a group which entered into communion with the Roman Catholic Church. This latter group, known initially as The Church of Assyria and Mosul, and latterly the Chaldean Catholics, continues also to maintain its own list of Chaldean Catholic patriarchs.[2]

Because of the complex history of Eastern Christianity, it is difficult to define one single lineage of patriarchs,[2] though some modern churches, such as the Assyrian Church of the East, claim all patriarchs through the centuries as the Assyrian Patriarch, even though the modern version of the church did not come into being until much more recently.

Language

Today, the ethnically Assyrian adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church celebrate the liturgy of Mar Addai and Mar Mari in Syriac, a dialect which (along with Eastern Aramaic) emerged in Assyria during the 5th century BC, as do Assyrian members of the Syriac Orthodox Church (largely centred in north east Syria and south east Turkey)), and Assyrian Protestant churches such as the Assyrian Evangelical Church and Assyrian Pentecostal Church.

At its peak, the Church of the East expanded from its Assyrian heartland, and it celebrated the liturgy in East Syriac in modern-day Syria, Israel, Palestine, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE, Cyprus, Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, India, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Indonesia, Mongolia, China and Japan. The church also uses Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Suryoyo which are the vernacular dialects of the Assyrian people as well as English, Arabic, Persian, Turkish and the languages of the countries of the Assyrian Diaspora.

List of Catholicoi of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and Patriarchs of the East until 1552

According to Church legend, the Apostleship of Edessa (Chaldea) is alleged to have been founded by Shimun Keepa (Saint Peter) (33–64),[7] Thoma Shlikha, (Saint Thomas), Tulmay (St. Bartholomew the Apostle) and of course Mar Addai, (St. Thaddeus) of the Seventy disciples. Saint Thaddeus was martyred c.66 AD.

Edessa era

- 1 Mar Aggai (c.66-81). First successor to the Apostleship of his spiritual director the Apostle Saint Thaddeus, one of the Seventy disciples. He in turn was the spiritual director of Mar Mari.

- 2 Palut of Edessa (c.81-87) renamed Mar Mari (c.87 – c.121) Second successor to the Apostleship of Mar Addai of the Seventy disciples.[8] During his days a bishopric was formally established at Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

- 3 Abris (Abres or Ahrasius) (121–148 AD) Judah Kyriakos relocates Jerusalem Church to Edessa in 136 AD. Reputedly a relative of Joseph[9]

- 4 Abraham (Abraham I of Kashker) (148–171 AD) Reputedly a relative of James the Just son of Joseph [10]

- 5 Yaʿqob I (Mar Yacob I) (c. 172–190 AD) son of his predecessor Abraham and therefore a relative of Joseph[11]

- 6 Ebid M’shikha (191–203)

- 7 Ahadabui (Ahha d'Aboui) (204–220 AD) First bishop of the East to get status as Catholic. Ordained in 231 AD in Jerusalem Council.

- 8 Shahaloopa of Kashker (Shahlufa) (220–266 AD)

Bar Aggai (267–c. 280)

Metropolitan of Seleucia-Ctesiphon elevated as titular Catholicos

Around 280, visiting bishops consecrated Papa bar Aggai as Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, thereby establishing the succession.[12] With him, heads of the church took the title Catholicos.

- 9 Papa bar Aggai (Mar Papa bar Gaggai) (c. 280–316 AD died 336)

- 10 Shemʿon bar Sabbaʿe (Simeon Barsabae) (coadjutor 317–336, Catholicos from 337–341 AD)

- 11 Shahdost (Shalidoste) (341–343 AD)[13]

- 12 Barbaʿshmin (Barbashmin) (343–346 AD). The apostolic see of Edessa is completely abandoned in 345 AD due to persecutions against the Church of the East.

- 13 Tomarsa (Toumarsa) (346–370 AD)

- 14 Qayyoma (Qaioma) (371–399 AD)

- 15 Isaac (399–410 AD)

Catholicos of the East with jurisdiction over Eastern provinces

Isaac was recognised as 'Grand Metropolitan' and Primate of the Church of the East at the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410. The acts of this Synod were later edited by the Patriarch Joseph (552–567) to grant him the title of Catholicos as well. This title for Patriarch Isaac in fact only came into use towards the end of the fifth century.

- 16 Ahha (Ahhi) (410–414 AD)

- 17 Yahballaha I (Yab-Alaha I) (415–420 AD)

- 18 Maʿna (Maana) (420 AD)

- 19 Farbokht (Frabokht) (421 AD)

- 20 Dadishoʿ (Dadishu I) 421–456 AD)

With Dadisho, the significant disagreement on the dates of the Catholicoi in the sources start to converge. In 424, under Mar Dadisho I, the Church of the East declared itself independent of all other churches; thereafter, its Catholicoi began to use the additional title of Patriarch.[12] During his reign, Nestorianism was subsequently denounced at the Council of Ephesus in 431.

- 21 Babowai (Babwahi) (457–484 AD)

- 22 Barsauma (484–485) opposed by

Acacius (Aqaq-Acace) (485–496/8 AD)

- 23 Babai (497–503)

- 24 Shila (503–523)

- 25 Elishaʿ (524–537)

Narsai intrusus (524–537)

- 26 Paul (539)

- 27 Aba I (540–552)

In 544 the Synod of Mar Aba I adopted the ordinances of the Council of Chalcedon.[14]

- 28 Joseph (552–556/567 AD)

- 29 Ezekiel (567–581)

- 30 Ishoʿyahb I (582–595)

- 31 Sabrishoʿ I (596–604)

- 32 Gregory (605–609)

vacant (609–628)

Babai the Great (coadjutor) 609–628; together with Abba (coadjutor) 609–628

From 628, the Maphrian also began to use the title Catholicos. See the List of Maphrians for details.

- 33 Ishoʿyahb II (628–645)

- 34 Maremmeh (646–649)

- 35 Ishoʿyahb III (649–659)

- 36 Giwargis I (661–680)

- 37 Yohannan I (680–683)

vacant (683–685)

- 38 Hnanishoʿ I (686–698)

Yohannan the Leper intrusus (691–693)

vacant (698–714)

- 39 Sliba-zkha (714–728)

vacant (728–731)

- 40 Pethion (731–740)

- 41 Aba II (741–751)

- 42 Surin (753)

- 43 Yaʿqob II (753–773)

- 44 Hnanishoʿ II (773–780)

In 775, the seat transferred from Seleucia-Ctesiphon to Baghdad, the recently established capital of the ʿAbbasid caliphs.[15]

- 45 Timothy I (780–823)

- 46 Ishoʿ Bar Nun (823–828)

- 47 Giwargis II (828–831)

- 48 Sabrishoʿ II (831–835)

- 49 Abraham II (837–850)

vacant (850–853)

- 50 Theodosius (853–858)

vacant (858–860)

- 51 Sargis (860–872)

vacant (872–877)

- 52 Israel of Kashkar intrusus (877)

- 53 Enosh (877–884)

- 54 Yohannan II bar Narsai (884–891)

- 55 Yohannan III (893–899)

- 56 Yohannan IV Bar Abgar (900–905)

- 57 Abraham III (906–937)

- 58 Emmanuel I (937–960)

- 59 Israel (961)

- 60 ʿAbdishoʿ I (963–986)

- 61 Mari (987–999)

- 62 Yohannan V (1000–1011)

- 63 Yohannan VI bar Nazuk (1012–1016)

vacant (1016–1020)

- 64 Ishoʿyahb IV bar Ezekiel (1020–1025)

vacant (1025–1028)

- 65 Eliya I (1028–1049)

- 66 Yohannan VII bar Targal (1049–1057)

vacant (1057–1064)

- 67 Sabrishoʿ III (1064–1072)

- 68 ʿAbdishoʿ II ibn al-ʿArid (1074–1090)

- 69 Makkikha I (1092–1110)

- 70 Eliya II Bar Moqli (1111–1132)

- 71 Bar Sawma (1134–1136)

vacant (1136–1139)

- 72 ʿAbdishoʿ III Bar Moqli (1139–1148)

- 73 Ishoʿyahb V (1149–1176)

- 74 Eliya III (1176–1190)

- 75 Yahballaha II (1190–1222)

- 76 Sabrishoʿ IV Bar Qayyoma (1222–1224)

- 77 Sabrishoʿ V ibn al-Masihi (1226–1256)

- 78 Makkikha II (1257–1265)

- 79 Denha I (1265–1281)

- 80 Yahballaha III (1281–1317) The Patriarchal Seat transferred to Maragha

- 81 Timothy II (1318–c. 1332)

- vacant (c. 1332–c. 1336)

- 82 Denha II (1336/7–1381/2)

- 83 Shemʿon II (c. 1365 – c. 1392) (dates uncertain)

- 83b Shemʿon III (c. 1403 – c. 1407) (existence uncertain)

- 84 Eliya IV (c. 1437)

- 85 Shemʿon IV Basidi (1437–1493, ob.1497)

- 86 Shemʿon V (1497–1501)

- 87 Eliya V (1502–1503)

- 88 Shemʿon VI (1504–1538)

- 89 Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–1558)

After the Schism of 1552

List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East from 1552 to 1830

By the Schism of 1552 the Church of the East was divided into many splinters but two main factions, of which one (the Church of Assyria and Mosul) entered into full communion with the Catholic Church and the other remained independent. A split in the former line in 1681 resulted in a third faction.

1. Eliya line in Alqosh:

In 1780, a group split from the Eliya line and elected:

| 2. Shemʿon line in Amid, Siirt, Urmia, Salmas, in communion with Rome until 1600:

Shemʿon line reintroduced hereditary succession; not recognised by Rome; moved to Qochanis

Shemʿon line in Qochanis formally broke communion with Rome, forming the Assyrian Church of the East in 1692:

| 3. In 1681, the Josephite line split from the Eliya line; with residence erected in Amid, in full communion with Rome:

|

The Eliya line (1) in Alqosh ended in 1804, and branch of Yohannan VIII Hormizd, that was in communion with Rome, merged with the Catholic Josephite line in Amid (3), with Yohannan VIII Hormizd recognised by the Holy See as Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans in 1830. This merged line, which relocated the see to Mosul, formed the contemporary unbroken patriarchal line of the Chaldean Catholic Church. For subsequent Chaldean Catholic Patriarchs, see List of Chaldean Catholic Patriarchs of Babylon.

The Shemʿon line (2) remained the only line not in full communion with the Catholic Church, which from the 19th-century continued to be known as the Assyrian Church of the East. For subsequent patriarchs in this line, see List of Patriarchs of the Assyrian Church of the East.

See also

Patriarchs of the East, of the Orthodox and Catholic churches of Eastern Christianity- List of Chaldean Catholic Patriarchs of Babylon

- Catholicos of the East

- Ancient Church of the East

- Province of the Patriarch

References

^ Walker 1985, p. 172: "this church had as its head a "catholicos" who came to be styled "Patriarch of the East" and had his seat originally at Seleucia-Ctesiphon (after 775 it was shifted to Baghdad)".

^ abc Wilmshurst 2000, p. 4.

^ Wigram 1910, p. 90.

^ Wigram 1910, p. 42-44.

^ Wigram 1910, p. 90-91.

^ Wigram 1910, p. 91.

^ I Peter, 1:1 and 5:13

^ Edwin Keith Broadhead, Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck, 2010 ) p 123.

^ Edwin Keith Broadhead, Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck, 2010 ) p 123.

^ Edwin Keith Broadhead, Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck, 2010 ) p 123.

^ Edwin Keith Broadhead, Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity (Mohr Siebeck, 2010 ) p 123.

^ ab Stewart 1928, p. 15.

^ St. Sadoth, Bishop of Seleucia and Ctesiphon, with 128 Companions, Martyrs.

^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 287-289.

^ Vine 1937, p. 104.

^ abcdefg Hage 2007, p. 473.

^ abcdefghijklmn Wilmshurst 2011, p. 477.

^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24.

^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 24-25.

^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 25.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian Patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon.

Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

Fiey, Jean Maurice (1979) [1963]. Communautés syriaques en Iran et Irak des origines à 1552. London: Variorum Reprints.

Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut.

Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer Verlag.

Jakob, Joachim (2014). Ostsyrische Christen und Kurden im Osmanischen Reich des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Münster: LIT Verlag.

Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

Murre van den Berg, Heleen H. L. (1999). "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 2 (2): 235–264.

Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian Missionary Enterprise: A Church on Fire. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W., eds. (2013). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Münster: LIT Verlag.

Tfinkdji, Joseph (1914). "L' église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui". Annuaire pontifical catholique. 17: 449–525.

Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. 11. pp. 157–323.

Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press.

Vosté, Jacques Marie (1930). "Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.-D. des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Le Muséon. 43: 263–316.

Vosté, Jacques Marie (1931). "Mar Iohannan Soulaqa, premier Patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l'union avec Rome (†1555)". Angelicum. 8: 187–234.

Wigram, William Ainger (1910). An Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church or The Church of the Sassanid Persian Empire 100-640 A.D. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers.

Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited.

Walker, Williston (1985) [1918]. A history of the Christian Church. New York: Scribner.

External links

- Nestorian Patriarchs