Lone pair

Lone pairs (shown as pairs of dots) in the Lewis structure of hydroxide

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom[1] and is sometimes called a non-bonding pair. Lone pairs are found in the outermost electron shell of atoms. They can be identified by using a Lewis structure. Electron pairs are therefore considered lone pairs if two electrons are paired but are not used in chemical bonding. Thus, the number of lone pair electrons plus the number of bonding electrons equals the total number of valence electrons around an atom.

Lone pair is a concept used in valence shell electron pair repulsion theory (VSEPR theory) which explains the shapes of molecules. They are also referred to in the chemistry of Lewis acids and bases. However, not all non-bonding pairs of electrons are considered by chemists to be lone pairs. Examples are the transition metals where the non-bonding pairs do not influence molecular geometry and are said to be stereochemically inactive. In molecular orbital theory (fully delocalized or otherwise), the concept of a lone pair is less distinct, but orbitals that are occupied but nonbonding (or mostly nonbonding) in character are frequently regarded as "lone pairs" as well.

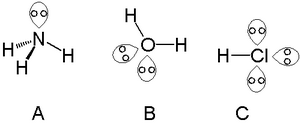

Lone pairs in ammonia (A), water (B), and hydrogen chloride (C)

A single lone pair can be found with atoms in the nitrogen group such as nitrogen in ammonia, two lone pairs can be found with atoms in the chalcogen group such as oxygen in water and the halogens can carry three lone pairs such as in hydrogen chloride.

In VSEPR theory the electron pairs on the oxygen atom in water form the vertices of a tetrahedron with the lone pairs on two of the four vertices. The H–O–H bond angle is with 104.5°, less than the 109° predicted for a tetrahedral angle, and this can be explained by a repulsive interaction between the lone pairs.[2][3][4]

Various computational criteria for the presence of lone pairs have been proposed. While electron density ρ(r) itself generally does not provide useful guidance in this regard, the laplacian of the electron density is revealing, and one criterion for the location of the lone pair is where L(r) = –∇2ρ(r) is a local maximum. The minima of the electrostatic potential V(r) is another proposed criterion. Yet another considers the electron localization function (ELF).[5]

Contents

1 Different descriptions of the lone pairs of water

2 Angle changes

3 Dipole moments

4 Unusual lone pairs

5 Stereogenic lone pairs

6 See also

7 References

Different descriptions of the lone pairs of water

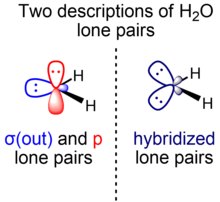

The symmetry-adapted and hybridized lone pairs of H2O

In elementary chemistry courses, the lone pairs of water are described as "rabbit ears": two equivalent electron pairs of approximately sp3 hybridization, while the HOH bond angle is 104.5°, slightly smaller than the ideal tetrahedral angle of arccos(–1/3) ≈ 109.47°. The smaller bond angle is rationalized by VSEPR theory by ascribing a larger space requirement for the two identical lone pairs compared to the two bonding pairs. At a higher degree of sophistication, this basic picture is modified using the theory of isovalent hybridization, in which spx hybrids with nonintegral values of x are allowed. In this picture, the O–H bonds are considered to be constructed from O bonding orbitals of ~sp4.0 hybridization (~80% p character, ~20% s character), which leaves behind O lone pairs orbitals of ~sp2.3 hybridization (~70% p character, ~30% s character). These deviations from idealized sp3 hybridization are consistent with Bent's rule.

However, an alternative description of water treats the lone pairs of water as energetically and geometrically distinct and possessing different symmetry (σ and π). In this model, one lone pair is represented by a lower energy σ-symmetry in-plane hybrid orbital that mixes s and p character (σ(out)), while the other lone pair is represented by a higher energy π-symmetry orbital perpendicular to the plane of the molecule of pure 2p character (p). In the fully delocalized canonical molecular orbital picture, these orbitals are given the Mulliken labels a1 and b1, in which the "nonbonding" a1 orbital actually consists of σ(out) mixed with the in-phase symmetry-adapted linear combination of the H(1s) orbitals (the small back lobe of σ(out) is able to interact). Thus, a1 is actually weakly bonding in character while b1 is truly nonbonding.

Both models are of value, but one must be careful of their applicability. Since only the canonical MOs (as opposed to any variety of localized MOs) are eigenfunctions of the effective Hamiltonian,[6] one must look at inequivalent, fully delocalized lone pair orbitals when interpreting the photoelectron spectrum of water (Koopmans' theorem), which does indeed show two signals corresponding to different energy levels for the lone pairs. However, any set of orbitals obtained by taking linear combination of symmetry-adapted orbitals via unitary transformations, as the equivalent lone pair hybrid orbitals are, result in the same electron density as the original set of orbitals. In this case, we can construct the two equivalent lone pair hybrid orbitals h and h' by taking linear combinations h = c1σ(out) + c2p and h' = c1σ(out) – c2p for an appropriate choice of coefficients c1 and c2. For chemical and physical properties of water that depend on the overall electron distribution of the molecule, the use of h and h' is just as valid as the use of σ(out) and p. In some cases, such a view is intuitively useful. For example, the hydrogen bonds of water form along the directions of the "rabbit ears" lone pairs, as a reflection of the increased availability of electrons in these regions. This view is supported computationally.[5]

Because of the popularity of VSEPR theory, the treatment of the water lone pairs as equivalent is prevalent in introductory chemistry courses, and many practicing chemists continue to regard it as a useful model. A similar situation arises when describing the two lone pairs on the carbonyl oxygen of a ketone.[7] However, the question of whether it is physically sound and conceptually useful to derive equivalent orbitals from symmetry-correct ones, from the standpoint of bonding theory and pedagogy and in light of modern experimental and computational data, is still a controversial one, with recent (2014 and 2015) articles opposing[8] and supporting[9] the practice.

Angle changes

The pairs often exhibit a negative polar character with their high charge density and are located closer to the atomic nucleus on average compared to the bonding pair of electrons. The presence of a lone pair decreases the bond angle between the bonding pair of electrons, due to their high electric charge which causes great repulsion between the electrons. They are also used in the formation of a dative bond. For example, the creation of the hydronium (H3O+) ion occurs when acids are dissolved in water and is due to the oxygen atom donating a lone pair to the hydrogen ion.

This can be seen more clearly when looked at it in two more common molecules. For example, in carbon dioxide (CO2), the oxygen atoms are on opposite sides of the carbon, whereas in water (H2O) there is an angle between the hydrogen atoms of 104.5º. Due to the repulsive force of the oxygen atom's lone pairs, the hydrogens are pushed further away, to a point where the forces of all electrons on the hydrogen atom are in equilibrium. This is an illustration of the VSEPR theory.

Dipole moments

Lone pairs can make a contribution to a molecule's dipole moment. NH3 has a dipole moment of 1.47 D. As the electronegativity of nitrogen (3.04) is greater than that of hydrogen (2.2) the result is that the N-H bonds are polar with a net negative charge on the nitrogen atom and a smaller net positive charge on the hydrogen atoms. There is also a dipole associated with the lone pair and this reinforces the contribution made by the polar covalent N-H bonds to ammonia's dipole moment. In contrast to NH3, NF3 has a much lower dipole moment of 0.24 D. Fluorine is more electronegative than nitrogen and the polarity of the N-F bonds is opposite to that of the N-H bonds in ammonia, so that the dipole due to the lone pair opposes the N-F bond dipoles, resulting in a low molecular dipole moment.[10]

Unusual lone pairs

A stereochemically active lone pair is also expected for divalent lead and tin ions due to their formal electronic configuration of ns2. In the solid state this results in the distorted metal coordination observed in the litharge structure adopted by both PbO and SnO.

The formation of these heavy metal ns2 lone pairs which was previously attributed to intra-atomic hybridization of the metal s and p states[11] has recently been shown to have a strong anion dependence.[12] This dependence on the electronic states of the anion can explain why some divalent lead and tin materials such as PbS and SnTe show no stereochemical evidence of the lone pair and adopt the symmetric rocksalt crystal structure.[13][14]

In molecular systems the lone pair can also result in a distortion in the coordination of ligands around the metal ion. The lead lone pair effect can be observed in supramolecular complexes of lead(II) nitrate, and in 2007 a study linked the lone pair to lead poisoning.[15] Lead ions can replace the native metal ions in several key enzymes, such as zinc cations in the ALAD enzyme, which is also known as porphobilinogen synthase, and is important in the synthesis of heme, a key component of the oxygen-carrying molecule hemoglobin. This inhibition of heme synthesis appears to be the molecular basis of lead poisoning (also called "saturnism" or "plumbism").[16][17][18]

Computational experiments reveal that although the coordination number does not change upon substitution in calcium-binding proteins, the introduction of lead distorts the way the ligands organize themselves to accommodate such an emerging lone pair: consequently, these proteins are perturbed. This lone-pair effect becomes dramatic for zinc-binding proteins, such as the above-mentioned porphobilinogen synthase, as the natural substrate cannot bind anymore - in those cases the protein is inhibited.

In Group 14 elements (the carbon group), lone pairs can manifest themselves by shortening or lengthening single (bond order 1) bond lengths,[19] as well as in the effective order of triple bonds as well.[20][21] The familiar alkynes have a carbon-carbon triple bond (bond order 3) and a linear geometry of 180° bond angles (figure A in reference [22]). However, further down in the group (silicon, germanium, and tin), formal triple bonds have an effective bond order 2 with one lone pair (figure B[22]) and trans-bent geometries. In lead, the effective bond order is reduced even further to a single bond, with two lone pairs for each lead atom (figure C[22]). In the organogermanium compound (Scheme 1 in the reference), the effective bond order is also 1, with complexation of the acidic isonitrile (or isocyanide) C-N groups, based on interaction with germanium's empty 4p orbital.[22][23]

Stereogenic lone pairs

| ⇌ |  |

| Inversion of a generic organic amine molecule at nitrogen | ||

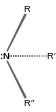

A lone pair can contribute to the existence of chirality in a molecule, when three other groups attached to an atom all differ. The effect is seen in certain amines, phosphines,[24]sulfonium and oxonium ions, sulfoxides, and even carbanions.

The resolution of enantiomers where the stereogenic center is an amine is usually precluded because the energy barrier for nitrogen inversion at the stereo center is low, which allow the two stereoisomers to rapidly interconvert at room temperature. As a result, such chiral amines cannot be resolved, unless the amine's groups are constrained in a cyclic structure (such as in Tröger's base).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lone pair. |

- Coordination complex

- Highest occupied molecular orbital

- Inert pair effect

- Ligand

- Shared pair

References

^ IUPAC Gold Book definition: lone (electron) pair

^ Organic Chemistry Marye Anne Fox, James K. Whitesell 2nd Edition 2001

^ Organic chemistry John McMurry 5th edition 2000

^ Concise Inorganic Chemistry J.D. Lee 4th Edition 1991

^ ab Kumar, Anmol; Gadre, Shridhar R.; Mohan, Neetha; Suresh, Cherumuttathu H. (2014-01-06). "Lone Pairs: An Electrostatic Viewpoint". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 118 (2): 526–532. doi:10.1021/jp4117003. ISSN 1089-5639..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Albright, T. A.; Burdett, J. K.; Whangbo, M.-H. (1985). Orbital Interactions in Chemistry. New York: Wiley. p. 102. ISBN 0471873934.

^ Ansyln, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

^ Clauss, Allen D.; Nelsen, Stephen F.; Ayoub, Mohamed; Moore, John W.; Landis, Clark R.; Weinhold, Frank (2014-10-08). "Rabbit-ears hybrids, VSEPR sterics, and other orbital anachronisms". Chemistry Education Research and Practice. 15 (4). doi:10.1039/C4RP00057A. ISSN 1756-1108.

^ Hiberty, Philippe C.; Danovich, David; Shaik, Sason (2015-07-07). "Comment on "Rabbit-ears hybrids, VSEPR sterics, and other orbital anachronisms". A reply to a criticism". 16 (3). doi:10.1039/C4RP00245H.

^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 40. ISBN 978-0130399137.

^ Stereochemistry of Ionic Solids J.D.Dunitz and L.E.Orgel, Advan. Inorg. and Radiochem. 1960, 2, 1–60

^ Electronic origins of structural distortions in post-transition metal oxides: experimental and theoretical evidence for a revision of the lone pair model D.J.Payne, R.G.Egdell, A.Walsh, G.W.Watson, J.Guo, P.-A.Glans, T.Learmonth and K.E.Smith, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 157403 doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.157403

^ The origin of the stereochemically active Pb(II) lone pair: DFT calculations on PbO and PbS A.Walsh and G.W.Watson, J. Sol. Stat. Chem. 2005, 178, 5 doi:10.1016/j.jssc.2005.01.030

^ Influence of the Anion on Lone Pair Formation in Sn(II) Monochalcogenides: A DFT Study A.Walsh and G.W.Watson, J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 18868 doi:10.1021/jp051822r

^ Gourlaouen, Christophe; Parisel, Olivier (15 January 2007). "Is an Electronic Shield at the Molecular Origin of Lead Poisoning? A Computational Modeling Experiment". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (4): 553–556. doi:10.1002/anie.200603037. PMID 17152108.

^ Jaffe, E. K.; Martins, J.; et al. (13 October 2000). "The Molecular Mechanism of Lead Inhibition of Human Porphobilinogen Synthase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (2): 1531–1537. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007663200. PMID 11032836.

^ Scinicariello, Franco; Murray, H. Edward; et al. (15 September 2006). "Lead and δ-Aminolevulinic Acid Dehydratase Polymorphism: Where Does It Lead? A Meta-Analysis". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1289/ehp.9448. PMC 1797830. PMID 17366816.

^ Chhabra, Namrata (November 15, 2015). "Effect of Lead poisoning on heme biosynthetic pathway". Clinical Cases: Biochemistry For Medics. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

^ Richards, Anne F.; Brynda, Marcin; Power, Philip P. (2004). "Effects of the alkali metal counter ions on the germanium–germanium double bond length in a heavier group 14 element ethenide salt". Chem. Commun. (14): 1592–1593. doi:10.1039/B401507J.

^ Power, Philip P. (December 1999). "π-Bonding and the Lone Pair Effect in Multiple Bonds between Heavier Main Group Elements". Chemical Reviews. 99 (12): 3463–3504. doi:10.1021/cr9408989. PMID 11849028.

^ Vladimir Ya. Lee; Akira Sekiguchi (22 July 2011). Organometallic Compounds of Low-Coordinate Si, Ge, Sn and Pb: From Phantom Species to Stable Compounds. John Wiley & Sons. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-119-95626-6.

^ abcd Spikes, Geoffrey H.; Power, Philip P. (2007). "Lewis base induced tuning of the Ge–Ge bond order in a "digermyne"". Chem. Commun. (1): 85–87. doi:10.1039/b612202g. PMID 17279269.

^ Power, Philip P. (2003). "Silicon, germanium, tin and lead analogues of acetylenes". Chemical Communications (17): 2091–101. doi:10.1039/B212224C. PMID 13678155.

^ Quin, L. D. (2000). A Guide to Organophosphorus Chemistry, LOCATION: John Wiley & Sons.

ISBN 0471318248.