Impalement

Vertical impalement

Impalement, as a method of execution and also as a method of torture, is the penetration of a human by an object such as a stake, pole, spear, or hook, often by complete or partial perforation of the torso. It was used particularly in response to "crimes against the state" and was regarded across a number of cultures as a very harsh form of capital punishment and recorded in myth and art. Impalement was also used during wartime to suppress rebellions, punish traitors or collaborators, and as a punishment for breaches of military discipline.

Offenses where impalement was occasionally employed include: contempt for the state's responsibility for safe roads and trade routes by committing highway robbery or grave robbery, violating state policies or monopolies, or subverting standards for trade. Offenders have also been impaled for a variety of cultural, sexual and religious reasons.

References to impalement in Babylonia and the Neo-Assyrian Empire are found as early as the 18th century BC.

Contents

1 Methods

1.1 Longitudinal impalement

1.1.1 Survival time

1.2 Transversal impalement

1.3 Variations

1.3.1 Gaunching

1.3.2 Hooks in the city wall

1.3.3 Hanged by the ribs

1.3.4 Bamboo torture

2 History

2.1 Antiquity

2.1.1 Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East

2.1.2 Pharaonic Egypt

2.1.3 Neo-Assyrian Empire

2.1.4 Achaemenid Persia

2.1.5 Ambiguous Biblical evidence

2.1.6 Rome

2.2 Europe

2.2.1 Transversal impalement

2.2.2 Longitudinal impalement

2.2.3 Heinous murderers

2.2.4 Vlad the Impaler

2.3 Ottoman Empire

2.3.1 Siege of Constantinople

2.3.2 Civil crimes

2.3.3 Klephts and rebels in Greece

2.3.4 Rebels elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire

2.3.5 Occurrences in genocides

3 References and notes

4 Bibliography

Methods

Longitudinal impalement

Impaling an individual along the body length has been documented in several cases, and the merchant Jean de Thevenot provides an eyewitness account of this, from 17th century Egypt, in the case of a Jewish man condemned to death for the use of false weights:[1]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

They lay the malefactor upon his belly, with his hands tied behind his back, then they slit up his fundament with a razor, and throw into it a handful of paste that they have in readiness, which immediately stops the blood. After that, they thrust up into his body a very long stake as big as a mans arm, sharp at the point and tapered, which they grease a little before; when they have driven it in with a mallet, till it come out at his breast, or at his head or shoulders, they lift him up, and plant this stake very streight in the ground, upon which they leave him so exposed for a day. One day I saw a man upon the pale, who was sentenced to continue so for three hours alive and that he might not die too soon, the stake was not thrust up far enough to come out at any part of his body, and they also put a stay or rest upon the pale, to hinder the weight of his body from making him sink down upon it, or the point of it from piercing him through, which would have presently killed him: In this manner he was left for some hours, (during which time he spoke) and turning from one side to another, prayed those that passed by to kill him, making a thousand wry mouths and faces, because of the pain he suffered when he stirred himself, but after dinner, the Basha sent one to dispatch him; which was easily done, by making the point of the stake come out at his breast, and then he was left till next morning, when he was taken down, because he stunk horridly.

Survival time

Mural on the ceiling of Avudaiyarkoil at Pudukottai District, Tamil Nadu, India showing the impalement scene.

The length of time which one managed to survive upon the stake is reported as quite varied, from a few seconds or minutes[2] to a few hours[3] or 1 to 3 days.[4] The Dutch overlords at Batavia, present day Jakarta, seem to have been particularly proficient in prolonging the lifetime of the impaled, one witnessing a man surviving 6 days on the stake,[5] another hearing from local surgeons that some could survive 8 or more days.[6] A critical determinant for survival length seems to be precisely how the stake was inserted: If it went into the "interior" parts, vital organs could easily be damaged, leading to a swift death. However, by letting the stake follow the spine, the impalement procedure would not damage the vital organs, and the person could survive for several days.[7]

Transversal impalement

Alternatively, the impalement could be transversely performed, for example in the frontal-to-dorsal direction, that is, from front (through abdomen,[8]chest[9] or directly through the heart[10]) to back or vice versa.[11]

In the Holy Roman Empire (and elsewhere in Central/Eastern Europe), women who killed their newborn especially keeping in mind any implications of witchcraft could be liable to be placed in an open grave, and have a stake hammered into their heart. A detailed description of an execution in this manner comes from 17th century Košice (then in Hungary, now in eastern Slovakia). A woman to be executed for infanticide involved an executioner and two assistants to help him. First, a grave some one-and-a-half ell deep was dug. The woman was placed within it, her hands and feet secured by driving nails through them. The executioner placed a small thorn bush upon her face. He then placed, and held vertically, a wooden stave at her heart to mark its location, while his assistants piled earth on the woman, keeping her head free of earth at the behest of the clerics, however, as to do otherwise would have quickened the death process. Once the earth had been piled upon her, the executioner grabbed with a pair of tongs a rod made of iron, which had been made red hot. He positioned the glowing iron rod beside the wooden stave, and as one of his assistants hammered the rod in, the other assistant emptied a trough of earth upon the woman's head. It is said that a scream was heard, and that the earth actually moved upwards for a moment, before all was over.[12]

Variations

Gaunching

Original in-image text from 1741 edition of Tournefort: "The Gaunche, a sort of punishment in use among the Turks."

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, travelling on botanical research in the Levant 1700–1702, observed both ordinary longitudinal impalement, but also a method called "gaunching", in which the condemned is hoisted up by means of a rope over a bed of sharp metal hooks. He is then released, and depending on how the hooks enter his body, he may survive in impaled condition for a few days.[13]

Forty years earlier than de Tournefort, de Thévenot described much the same process, adding that it was seldom used because it was regarded as too cruel.[14] Some 80 years prior to de Thevenot, in 1579, Hans Jacob Breuning von Buchenbach[15] witnessed a variant of the gaunching ritual. A large iron hook was fixed on the horizontal cross-bar of the gallows and the individual was forced upon this hook, piercing him from the abdomen through his back, so that he hung from it, hands, feet and head downward. On top of the cross bar, the executioner situated himself and performed various torture on the impaled man below him.[16]

Hooks in the city wall

While gaunching as de Tournefort describes involves the erection of a scaffold, it seems that in the city of Algiers, hooks were embedded in the city walls, and on occasion, people were thrown upon them from the battlements.

Thomas Shaw,[17] who was chaplain for the Levant Company stationed at Algiers during the 1720s, describes the various forms of executions practiced as follows:[18]

... but the Moors and Arabs are either impaled for the same crime, or else they are hung up by the neck, over the battlements of the city walls, or else they are thrown upon the chingan or hooks that are fixed all over the walls below, where sometimes they break from one hook to another, and hang in the most exquisite torments, thirty or forty hours.

According to one source, these hooks in the wall as an execution method were introduced with the construction of the new city gate in 1573. Before that time, gaunching as described by de Tournefort was in use.[19] As for the actual frequency of throwing persons on hooks in Algiers, Capt. Henry Boyde notes[20] that in his own 20 years of captivity there, he knew of only one case where a Christian slave who had murdered his master had met that fate, and "not above" two or three Moors besides.[21] Taken captive in 1596, the barber-surgeon William Davies relates something of the heights involved when thrown upon hooks (although it is somewhat unclear if this relates specifically to the city of Algiers, or elsewhere in the Barbary States): "Their ganshing is after this manner: he sitteth upon a wall, being five fathoms high, within two fathoms of the top of the wall; right under the place where he sits, is a strong iron hook fastened, being very sharp; then he is thrust off the wall upon this hook, with some part of his body, and there he hangeth, sometimes two or three days, before he dieth." Davies adds that "these deaths are very seldom", but that he had personally witnessed it.[22]

Hanged by the ribs

"A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows," by William Blake. Originally published in Stedman's Narrative.

A slightly variant way of executing people by means of impalement was to force an iron meat hook beneath a person's ribs and hang him up to die slowly. This technique was in 18th century Ottoman-controlled Bosnia called the cengela,[23] but the practice is also attested, for example, in 1770s Dutch Suriname as a punishment meted out to rebellious slaves.[24]

Bamboo torture

A recurring horror story on many websites and popular media outlets is that Japanese soldiers during World War II inflicted bamboo torture upon prisoners of war.[25] The victim was supposedly tied securely in place above a young bamboo shoot. Over several days, the sharp, fast growing shoot would first puncture, then completely penetrate the victim's body, eventually emerging through the other side. However, no conclusive evidence exists that this form of impalement ever actually happened.[26]

History

Antiquity

Mesopotamia and the ancient Near East

The earliest known use of impalement as a form of execution occurred in civilizations of the ancient Near East. For example, the Code of Hammurabi, promulgated about 1772 BC[27] by the Babylonian king Hammurabi specifies impaling for a woman who killed her husband for the sake of another man.[28] In the late Isin/Larsa period, from about the same time, it seems that, in some city states, mere adultery on the wife's part (without murder of her husband mentioned) could be punished by impalement.[29] From the royal archives of the city of Mari (at the Syrian-Iraqi border by the western bank of Euphrates), most of it also roughly contemporary to Hammurabi, it is known that soldiers taken captive in war were on occasion impaled.[30] Roughly contemporary with Babylonia under Hammurabi, king Siwe-Palar-huhpak of Elam, a country lying directly east of Babylonia in present-day Iran, made official edicts in which he threatened the allies of his enemies with impalement, among other terrible fates.[31] For acts of perceived great sacrilege, some individuals, in diverse cultures, have been impaled for their effrontery. For example, roughly 1200 BC, merchants of Ugarit express deep concern to each other that a fellow citizen is to be impaled in the Phoenician town Sidon, due to some "great sin" committed against the patron deity of Sidon.[32]

Pharaonic Egypt

During Dynasty 19, Merneptah had Libu prisoners of war impaled ("caused to be set upon a stake") to the south of Memphis, following an attempted invasion of Egypt during his Regnal Year 5.[33] The relevant determinative for ḫt ("stake") depicts an individual transfixed through the abdomen.[34] Other Egyptian kings employing impalements include Sobekhotep II, Akhenaten, Seti, and Ramesses IX.[34]

Neo-Assyrian Empire

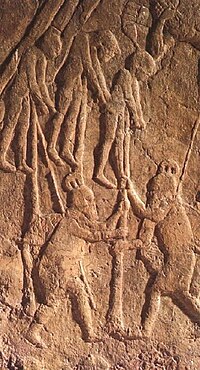

Impalement of Judeans in a Neo-Assyrian relief

Evidence by carvings and statues is found as well, for example from Neo-Assyrian empire (c. 934–609 BCE). The image of the impaled Judeans is a detail from the public commemoration of the Assyrian victory in 701 BC after the Siege of Lachish,[35] under King Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC), who proceeded similarly against the inhabitants of Ekron during the same campaign.[36] From Sennacherib's father Sargon II's time (r. 722–705 BCE), a relief from his palace at Khorsabad shows the impalement of 14 enemies during an attack on the city of Pazashi.[37] A peculiarity[38] about the "Neo-Assyrian" way of impaling was that the stake was "driven into the body immediately under the ribs",[39] rather than along the full body length. For the Neo-Assyrians, mass executions seem to have been not only designed to instill terror and to enforce obedience, but also, it can seem, as proofs of their might that they took pride in. For example, Neo-Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BC) was evidently proud enough of his bloody work that he committed it to monument and eternal memory as follows:[40]

I cut off their hands, I burned them with fire, a pile of the living men and of heads over against the city gate I set up, men I impaled on stakes, the city I destroyed and devastated, I turned it into mounds and ruin heaps, the young men and the maidens in the fire I burned

Paul Kern,[41] in his (1999) "Ancient Siege Warfare", provides some statistics on how different Neo-Assyrian kings from the times of Ashurnasirpal II commemorated their punishments of rebels.[42]

Although impalement of rebels and enemies is particularly well-attested from Neo-Assyrian times, the 14th century BCE Mitanni king Shattiwaza charges his predecessor, the usurper Shuttarna III for having delivered unto the (Middle) Assyrians[43] several nobles, who had them promptly impaled.[44] Some scholars have said, though, that it is only with king Ashur-bel-kala (r. 1074–1056) that we have solid evidence that punishments like flaying and impaling came into use.[45] From the Middle Assyrian period, we have evidence about impalement as a form of punishment relative to other types of perceived crimes as well. The law code discovered and deciphered by Dr. Otto Schroeder[46] contains in its paragraph 51 the following injunction against abortion:[47]

If a woman with her consent brings on a miscarriage, they seize her, and determine her guilt. On a stake they impale her, and do not bury her; and if through the miscarriage she dies, they likewise impale her and do not bury her.

Achaemenid Persia

The Greek historian Herodotus recounts that, when Darius I, king of Persia, conquered Babylon, he impaled 3000 Babylonians.[48] In the Behistun Inscription, Darius himself boasts of having impaled his enemies.[49]

Ambiguous Biblical evidence

Some controversy[citation needed] exists over different Bible translations concerning the actual fate of the 5th century BC Persian minister Haman and his ten sons, whether they were impaled or hanged[50] For example, the English Standard Version, Esther 5:14 opts for hanging,[51] whereas The New International Reader's version opts for impalement.[52]

The Assyriologist Paul Haupt opts for impalement in his 1908 essay "Critical notes on Esther",[53] while Benjamin Shaw has an extended discussion of the topic on the website ligonier.org from 2012.[54]

Other passages in the Bible may allude to the practice of impalement, such as II Samuel 21:9 concerning the fate of the sons of Saul, where some English translations use the verb "impale", but others use "hang".[55]

Although we lack conclusive evidence either way for whether Hebrew law allowed for impalement, or for hanging (whether as a mode of execution or for display of the corpse), the Neo-Assyrian method of impalement as seen in carvings could, perhaps, equally easily be seen as a form of hanging upon a pole, rather than focusing upon the stake's actual penetration of the body.

Rome

From John Granger Cook, 2014: "Stipes is Seneca's term for the object used for impalement. This narrative and his Ep. 14.5 are the only two textually explicit references to impalement in Latin texts:"

I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made differently by different [fabricators]; some individuals suspended their victims with heads inverted toward the ground; some drove a stake (stipes) through their excretory organs/genitals; others stretched out their [victims'] arms on a patibulum [cross bar]; I see racks, I see lashes ...

Video istic cruces ne unius quidem generis sed aliter ab aliis fabricatas; capite quidam conuersos in terram suspendere, alii per obscena stipitem egerunt, alii brachia patibulo explicuerunt; video fidiculas, video uerbera ... [56]

Europe

Transversal impalement

Within the Holy Roman Empire, in article 131 of the 1532 Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, the following punishment was stated for women found guilty of infanticide. Generally, they should be drowned, but the law code allowed for, in particularly severe cases, that the old punishment could be implemented. That is, the woman would be buried alive, and then a stake would be driven through her heart.[57] Similarly, burial alive, combined with transversal impalement is attested as an early execution method for people found guilty of adultery. For example, from the 1348 statutes of Zwickau, it seems that an adulterous couple could be punished in the following way: They were to be placed on top of each other in a grave, with a layer of thorns between them. Then, a single stake was to be hammered through them.[58] A similar punishment by impalement for a proven male adulterer is mentioned in a 13th-century ordinance for Bohemian mining town Jihlava (then and German Iglau),[59] whereas in a 1340 Vienna statute, the husband of a woman caught in flagrante in adultery could, if he wished to, demand that his wife and her lover be impaled, or alternatively demand a monetary restitution.[60] Occasionally, women found guilty of witchcraft have been condemned to be impaled. In 1587 Kiel, 101-year-old Sunde Bohlen was, on being condemned as a witch, buried alive, and afterwards had a stake driven through her heart.[61]

Rapists of virgins and children are also attested to have been buried alive, with a stake driven through them. In one such judicial tradition, the rapist was to be placed in an open grave, and the rape victim was ordered to make the three first strokes on the stake herself; the executioners then finishing the impalement procedure.[62] Serving as an example of the fate of a child molester, in August 1465 in Zurich, Switzerland, Ulrich Moser was condemned to be impaled, for having sexually violated six girls between the ages four and nine. His clothes were taken off, and he was placed on his back. His arms and legs were stretched out, each secured to a pole. Then a stake was driven through his navel down into the ground. Thereafter, people left him to die.[63]

Longitudinal impalement

Cases of longitudinal impalement typically occur in the context of war or as a punishment for robbery, the latter being attested to as the practice in Central and Eastern Europe.

Individuals accused of collaborating with the enemy have, on occasion, been impaled. For example, in 1632 during the Thirty Years' War, the German officer Fuchs was impaled on suspicion of defecting to the Swedes,[64] a Swedish corporal was likewise impaled for trying to defect to the Germans.[65] In 1654, under the Ottoman siege of the Venetian garrison at Crete, several peasants were impaled for supplying provisions to the besieged.[66] Likewise in 1685, some Christians were impaled by the Hungarians for having provided supplies to the Turks.[67]

In 1677, a particularly brutal German General Kops leading the forces of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I who wanted to keep Hungary dominated by the Germans, rather than allow it to become dominated by the Turks, began impaling and quartering his Hungarian subjects/opponents. An opposing general on the Hungarian side, Wesselényi, responded in kind, by flaying alive Imperial troops, and fixing sharp iron hooks in fortress walls, upon which he threw captured Germans to be impaled. Finally, Emperor Leopold I had had enough of the mutual bloodshed, and banished Kops in order to establish a needed cessation of hostilities.[68] After the Treaty of The Hague (1720), Sicily fell under Habsburg rule, but the locals deeply resented the German overlords. One parish priest (who exhorted his parishioners to kill the Germans) is said to have broken into joy when a German soldier arrived at his village, exclaiming that a whole eight days had gone by since he had last killed a German, and shot the soldier off his horse. The priest was later impaled.[69] In the short-lived 1784 Horea Revolt against the Austrians and Hungarians, the rebels gained hold of two officers, whom they promptly impaled. On their side, the imperial troops got hold of Horea's 13-year-old son, and impaled him. That seems to have merely inflamed the rebel leader's determination, although the revolt was quashed shortly afterwards.[70] After the revolt was crushed by early 1785, some 150 rebels are said to have been impaled.[71]

From 1748 onwards, German regiments organized manhunts on "robbers" in Hungary/Croatia, impaling those who were caught.[72]

Heinous murderers

Occasionally, individual murderers were perceived to have been so heinous that standard punishments like beheading or being broken on the wheel were regarded as incommensurate with their crimes, and extended rituals of execution that might include impalement were devised. An example is that of Pavel Vašanský (Paul Wasansky in German transcript), who was executed on 1 March 1570 in Ivančice in present-day Czech Republic, on account of 124 confessed murders (he was a roaming highwayman). He underwent a particularly gruelling execution procedure: first, his limbs were cut off and his nipples were ripped off with glowing pincers; he was then flayed, impaled and finally roasted alive. A pamphlet that purports to give Wasansky's verbatim confession, does not record how he was apprehended, nor what means of torture was used to extract his confessions.[73]

Other such accounts of "heinous murderers" in which impalement is a prominent element include cases in 1504 and 1519,[74] the murderer nicknamed Puschpeter executed in 1575 for killing thirty people, including six pregnant women whose unborn children he ate in the hope of thereby acquiring invisibility,[75] the head of the Pappenheimer family in 1600,[76] and an unnamed murderer executed in Breslau in 1615, who under torture had confessed to 96 acts of murder by arson.[77]

Vlad the Impaler

Woodblock print of Vlad III "Dracula" attending a mass impalement

During the 15th century, Vlad III ("Dracula"), Prince of Wallachia, is credited as the first notable figure to prefer this method of execution during the late medieval period,[78] and became so notorious for its liberal employment that among his several nicknames he was known as Vlad the Impaler.[79] After being orphaned, betrayed, forced into exile and pursued by his enemies, he retook control of Wallachia in 1456. He dealt harshly with his enemies, especially those who had betrayed his family in the past, or had profited from the misfortunes of Wallachia. Though a variety of methods were employed, he has been most associated with his use of impalement. The liberal use of capital punishment was eventually extended to Saxon settlers, members of a rival clan,[80] and criminals in his domain, whether they were members of the boyar nobility or peasants, and eventually to any among his subjects that displeased him. Following the multiple campaigns against the invading Ottoman Turks, Vlad would never show mercy to his prisoners of war. After The Night Attack of Vlad Ţepeş in mid-June 1462 failed to assassinate the Ottoman sultan, the road to Târgovişte, the capital of Vlad's principality of Wallachia, eventually became inundated in a "forest" of 20,000 impaled and decaying corpses, and it is reported that Mehmet II's invading army of Turks turned back to Constantinople in 1462 after encountering thousands of impaled corpses along the Danube River.[80]Woodblock prints from the era portray his victims impaled from either the frontal or the dorsal aspect, but not vertically.

As an example of how Vlad Țepeș soon became iconic for all horrors unimaginable, the following pamphlet from 1521 pours out putative incidents like this one:

He let children be roasted; those, their mothers were forced to eat. And (he) cut off the breasts of women; those, their husbands were forced to eat. After that, he had them all impaled

— .[81]

Ottoman Empire

Longitudinal impalement is an execution method often attested within the Ottoman Empire, for a variety of offenses, it was done mostly as a warning to others or to terrify.[82]

Siege of Constantinople

The Ottoman Empire used impalement during, and before, the last siege of Constantinople in 1453.[78] For example, during the buildup phase to the great siege the year before, in 1452, the sultan declared that all ships sailing up or down through the Bosphorus had to anchor at his fortress there, for inspection. One Venetian captain, Antonio Rizzo, sought to defy the ban, but his ship was hit by a cannonball. He and his crew were picked up from the waters, the crew members to be beheaded (or sawn asunder according to Niccolò Barbaro[83]), whereas Rizzo was impaled.[84] In the early days of the siege in May 1453, contingents of the Ottoman army made mop-up operations at minor fortifications like Therapia and Studium. The surrendered soldiers, some 40 individuals from each place, were impaled.[85]

Civil crimes

Within the Ottoman Empire, some civil crimes (rather than rebel activity/treasonous behavior), such as highway robbery, might be punished by impalement. For some periods at least, executions for civil crimes were claimed to have been rather rare in the Ottoman Empire. For example, Aubry de La Motraye, lived in the realm for 14 years from 1699 to 1713 and claimed that he hadn't heard of twenty thieves in Constantinople during that time. As for highway robbers, who sure enough had been impaled, Aubry heard of only 6 such cases during his residence there.[86] Staying at Aleppo from 1740–54, Alexander Russell notes that in the 20 years gone by, there were no more than "half a dozen" public executions there.[87] Jean de Thévenot, traveling in the Ottoman Empire and its territories like Egypt in the late 1650s, emphasizes the regional variations in impalement frequency. Of Constantinople and Turkey, de Thévenot writes that impalement was "not much practised" and "very rarely put in practice." An exception he highlighted was the situation of Christians in Constantinople. If a Christian spoke or acted out against the "Law of Mahomet", or consorted with a Turkish woman, or broke into a mosque, then he might face impalement unless he converted to Islam. In contrast, de Thévenot says that in Egypt impalement was a "very ordinary punishment" against the Arabs there, whereas Turks in Egypt were strangled in prison instead of being publicly executed like the natives.[88] Thus, the actual frequency of impalement within the Ottoman Empire varied greatly, not only from time to time, but also from place to place, and between different population groups in the empire.

Highway robbers were still impaled into the 1830s, but one source says the practice was rare by then.[89] Travelling to Smyrna and Constantinople in 1843, Stephen Massett[90] was told by a man who witnessed the event that "just a few years ago", a dozen or so robbers were impaled at Adrianople. All of them, however, had been strangled prior to impalement.[91] Writing around 1850, the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard mentions that the latest case he was acquainted with happened "about ten years ago" in Baghdad, on four rebel Arab sheikhs.[92]

Impalement of pirates, rather than highway robbers, is also occasionally recorded. In October 1767, for example, Hassan Bey, who had preyed on Turkish ships in the Euxine Sea for a number of years, was captured and impaled, even though he had offered 500,000 ducats for his pardon.[93]

Klephts and rebels in Greece

During the Ottoman rule of Greece, impalement became an important tool of psychological warfare, intended to put terror into the peasant population. By the 18th century, Greek bandits turned guerrilla insurgents (known as klephts) became an increasing annoyance to the Ottoman government. Captured klephts were often impaled, as were peasants that harbored or aided them. Victims were publicly impaled and placed at highly visible points, and had the intended effect on many villages who not only refused to help the klephts, but would even turn them in to the authorities.[94] The Ottomans engaged in active campaigns to capture these insurgents in 1805 and 1806, and were able to enlist Greek villagers, eager to avoid the stake, in the hunt for their outlaw countrymen.[95]

Impalement was, on occasion, aggravated with being set over a fire, the impaling stake acting as a spit, so that the impaled victim might be roasted alive.[96] Among other severities, Ali Pasha, an Albanian-born Ottoman noble who ruled Ioannina, had rebels, criminals, and even the descendants of those who had wronged him or his family in the past, impaled and roasted alive. For example, Thomas Smart Hughes, visiting Greece and Albania in 1812–13, says the following about his stay in Ioannina:[97]

Here criminals have been roasted alive over a slow fire, impaled, and skinned alive; others have had their extremities chopped off, and some have been left to perish with the skin of the face stripped over their necks. At first I doubted the truth of these assertions, but they were abundantly confirmed to me by persons of undoubted veracity. Some of the most respectable inhabitants of loannina assured me that they had sometimes conversed with these wretched victims on the very stake, being prevented from yielding to their torturing requests for water by fear of a similar fate themselves. Our own resident, as he was once going into the serai of Litaritza, saw a Greek priest, the leader of a gang of robbers, nailed alive to the outer wall of the palace, in sight of the whole city.

During the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832), Greek revolutionaries or civilians were tortured and executed by impalement. A German witness of the Constantinople massacre (April 1821) narrates the impalement of about 65 Greeks by Turkish mob.[98] In April 1821, thirty Greeks from the Ionian island of Zante (Zakynthos) had been impaled in Patras, in front of the British consulate. This was recorded in the diary of the French consul Hughes Pouqueville and published by his brother François Pouqueville.[99]Athanasios Diakos, a klepht and later a rebel military commander, was captured after the Battle of Alamana (1821), near Thermopylae, and after refusing to convert to Islam and join the Ottoman army, he was impaled.[100] Diakos became a martyr for a Greek independence and was later honored as a national hero.[101][102] Non-combatant Greeks (elders, monks, women etc.) were impaled around Athens during the first year of the revolution (1821).[103]

Rebels elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire

Impaling perceived rebels was an attested practice in other parts of the empire as well, such as the 1809 quelling of a Bosnian revolt,[104] and during the Serbian Revolution (1804–1835) against the Ottoman Empire, about 200 Serbs were impaled in Belgrade in 1814.[105] Historian James J. Reid,[106] in his Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839–1878, notes several instances of later use, in particular in times of crises, ordered by military commanders (if not, that is, directly ordered by the supreme authority possessed by the sultan). He notes late instances of impalement during rebellions (rather than cases of robbery) like the Bosnian revolt of 1852, during the Cretan insurrection of 1866–69, and during the insurrections in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1876–77.[107]

In the Nobel Prize-winning novel The Bridge on the Drina, by Ivo Andrić, in the third chapter is described impalement of a Bosnian Serb, who was trying to sabotage the bridge's construction.

Occurrences in genocides

Purported image of a Polish prisoner of war being tortured by Bolshevik soldiers, Polish–Soviet War, 1918 image by Frenchman telling his story to The New York Times, 1920 [108]

Impalement during the Assyrian and Armenian genocides has also been purported.

Aurora Mardiganian, a survivor of the Armenian genocide of 1915–1923, claimed sixteen young Armenian girls were "crucified" by Ottomans. The film Auction of Souls (1919), which was based on her book Ravished Armenia, showed the victims nailed to crosses. However, almost 70 years later Mardiganian claimed that the scene was inaccurate:[109]

"The Turks didn't make their crosses like that. The Turks made little pointed crosses. They took the clothes off the girls. They made them bend down, and after raping them, they made them sit on the pointed wood, through the vagina. That's the way they killed - the Turks. Americans have made it a more civilized way. They can't show such terrible things."

A Russian clergyman visiting ravaged Christian villages in northwestern Persia claimed to find the remains of several impaled people. He wrote: "The bodies were so firmly fixed, in some instances, that the stakes could not be withdrawn; it was necessary to saw them off and bury the victims as they were."[110]

References and notes

^ Thévenot (1687) p. 259 Other highly detailed accounts on methods are:

1. Extremely detailed description of the execution of Archbishop Serapheim in 1601. Vaporis (2000), pp. 101–102 2. Jean Coppin's account from 1640s Cairo, very similar to Thévenot's, Raymond (2000), p. 240 3. Stavorinus (1798) p. 288–291 4. von Taube (1777) footnote ** p. 70–71 5. The regrettably highly partisan "Aiolos (2004)", notes on methods partly from Guer, see for example, Guer (1747),p. 162 6. d'Arvieux (1755), p. 230–31 7. Recollection 20 years after second-hand narration, Massett (1863), p. 88–89 8. Ivo Andric's novel "The Bridge on the Drina", follows Serapheim execution (1.) closely. Excerpt: The Bridge on the Drina 9. A literary rendition in The Casket, from 1827, Purser (1827), p. 337 10. Koller (2004), p. 145–46

^ 2 died during impalement process, Blount (1636), p. 52 9 minutes, 1773 case, Hungary: Korabinsky (1786) p. 139

^ 1800 assassin of General Kleber a few hours Shepherd (1814)p. 255, six hours Hurd (1814),p. 308

^ fifteen hours Bond (1856) p. 172–73 24+ hours von Taube (1777), footnote ** p. 70–71, Hartmann (1799)p. 520, two to three days von Troilo (1676) p. 45, Hueber (1693) p. 480, Dampier (1729)p. 140, "Aiolos (2004)", d'Arvieux (1755), p. 230–31, Moryson, Hadfield (2001), pp. 170–171 two to three days in warm weather, dead by midnight in cold, Mentzel, Allemann (1919), p. 102

^ de Pages (1791) p. 284

^ Stavorinus (1798)p. 288–291

^ For following the spine: von Taube (1777), footnote ** p. 70–71, Stavorinus (1798)p. 288–291 Another description, using a 15 cm thick stake, let it pass between the liver and the rib cage, Koller (2004), p. 145

^ von Meyer von Knonau (1855)p. 176, column 2, Example of thrusting a roasting spit through the stomach on orders of 16th Central Asian ruler Mirza Abu Bakr Dughlat upon his own nephew, Elias, Ross (1898), p. 227

^ For extra-cardial chest impalement Döpler (1697) p. 371

^ Roch (1687)pp. 350–51

^ A possible case of 16th century dorsal-to-front impalement is given by di Varthema (1863) p. 147 See also wood block print in Dracula subsection. In addition, the alleged "bamboo torture" seems to presume a dorsal-to-front impalement, see specific sub-section

^ Wagner (1687), p. 55 NOTE: The German word "Pfahl" (with the associated verb "zu pfählen") refers to a wooden stake, and is the word used in influential law texts like the 1532 Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, so the reader should not assume that the use of a heated metal rod was the standard procedure. For 1532 law text, see for example, Koch (1824) p. 63

^ de Tournefort (1741) p. 98–100 A detailed description of the apparatus and procedure of gaunching can be found in Mundy (1907), pp. 55–56 and in Moryson, Hadfield (2001), pp. 170–171

^ Thévenot (1687)p. 68–69. For a fourth description plus drawing, see Schweigger (1613), p. 173 Schweigger adds that many times, people are allowed to shorten the gaunched individual's time of misery by cutting his throat or decapitating him. Alexander Russell, from 1740s Aleppo knew of instances of "gaunching", but said those were rare, compared with other types of capital punishment.Russell (1794)p. 334

^ Breuning von Buchenbach, Hans Jakob

^ Buchenbach (1612), pp. 86–87

^ Thomas Shaw

^ Shaw (1757) p. 253–254 Shaw's contemporary John Braithwaite reports impalement and throwing onto hooks for Morocco as well, Braithwaite (1729) p. 366 On Morocco and Fez, see also the travel account by Sieur Mouette, who was captive there from 1670 to 1682, Stevens (1711), p. 69

^ Morgan (1729) p. 392

^ in one of his acerbic comments and footnotes to translated accounts from Catholic priests' narratives of the redemption of slaves. Examples of other such acerbic notes: Boyde (1736) p. 3, p. 25, p. 35, p. 44 (compares French and Algerine slavery), p. 45, p. 51, p. 52

^ Boyde (1736) p. 75, footnote

^ Osborne (1745), p. 478

^ Koller (2004), p. 146

^ Stedman (1813) p. 116

^ As an example of popular promotion of this horror story, see for example:WW2 People's WarJAPANESE TORTURE TECHNIQUES

^ http://mentalfloss.com/article/23038/9-insane-torture-techniques

^ Middle chronology is used here

^ Article 153 in: Harper (1904), The Code of Hammurabi

^ Tetlow (2004) p. 34

^ Hamblin (2006), p. 208

^ Herrenschmidt, Bottéro (2000), p. 84

^ Mayer, ed. (2005), p. 141

^ Kitchen, Kenneth (2002). Ramesside inscriptions translated and annotated: Translations. Volume 4: Merenptah and the late Nineteenth Dynasty. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. p. 1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab http://ifpeakoilwerenoobject.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/impalements-in-antiquity-2.html

^ Ussishkin, Amit (2006), p. 346

^ Ekron incident from Sennacherib's own self-glorification, see Callaway (1995), p. 169

^ Relief and text in Ephʿal (2009), p. 51–52

^ Relative to later impalement practices, at least

^ Layard (1850) p. 374

^ Olmstead (1918), p. 66

^ Paul Kern

^ Kern (1999), p. 68–76, Relative to impalement, for example, Ashurnasirpal II is credited with 5 distinct incidents, Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BC). For a number of examples of impalement of rebels and subjugated people under Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, see Olmstead (1921), Battle at Sugania p. 348,Siege of Til Bashere p. 354, Battle of Arzashkun p. 360, Battle of Kulisi p. 368, Battle of Kinalua p. 378 For the last, see also Bryce (2012), p. 244 Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727), For some specifics on Tiglath-Pileser's policy, see for example, Crouch (2009), p. 39–41 and Ashurbanipal (r.668-627 BC), Ashurbanipal congratulates himself once over having impaled fleeing survivors from towns he has burnt down, Ehrlich (2004), p. 5

^ where Ashur-uballit I was king at that time

^ Kuhrt (1995), p. 292 and Gadd (1965), p. 9

^ Richardson, Laneri (2007), p. 197

^ Schroeder (1920), Keilschrifttexte aus Assur verschiedenen Inhalts

^ Jastrow (1921), p. 48–49

^ Herodotus: A New and Literal Version from the Text of Baehr by Henry Cary, page 236

^ Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, p. 123

^ Haman conspired to have all the Jews in the empire killed, the Book of Esther tells that story, and how Haman's plan was thwarted, and he was given the punishment he had thought to mete out to Mordecai.

^ Book of Esther, ESV Bible edition

^ Book of Esther, NIRV Bible edition

^ Haupt (1908), p. 122, 152, 154, 170

^ Shaw (2012), Was Haman Hanged or Impaled?

^ Compare Translations for 2 Samuel 21:9

^ Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World by John Granger Cook, 2014, published by Mohr Siebeck,

ISBN 9783161531248

^ For law text, Koch (1824) p. 63

^ Engel, Jacob (2006), p. 75 A similar punishment of the couple by impalement for adultery if caught in the act is mentioned in Bavarian sources as well, see His (1928), p. 150

^ Schwetschke (1789), col. 692

^ Ehrlich (2005), p. 42

^ Fick (1867), p. 14

^ Engelmann (1834)p. 158

^ Osenbrüggen (1868), p. 297

^ Schwab (1827), p. 256

^ Gottfried, van Hulsius (1633), p. 462

^ Han (1669), p. 203

^ Beer (1713), p. 127

^ von Loen (1751), p. 420–422

^ von Imhoff (1736), p. 1051

^ Mannheimer Zeitung (1784), p. 638

^ Vehse, Demmler (1856), p. 318

^ Woltersdorf (1812)p. 267

^ Daschitsky (1570), [https://books.google.com/books?id=h_xXAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA12 p. 1

^ Wiltenburg (2012), pp. 124–125

^ Bastian (1860), p. 105

^ Muir (1997), pp. 110–111

^ Roch (1687), p. 249

^ ab Reid, (2000), p. 440

^ Florescu (1999)

^ ab Axinte, Dracula: Between myth and reality

^ "er liess kinnder praten die musten ire mütter essen. Und schneyd den frawen den prüst ab den musten ire man essen. Darnach liess er sie all spissen.", Gutknecht (1521), p. 7

^ James J. Reid (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839-1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 440–. ISBN 978-3-515-07687-6.

^ Philippides, Hanak (2011), p. 587

^ Runciman (1965), p. 67

^ Pears, (2004), p. 253

^ de La Mottraye p. 188

^ Russell (1794) p. 331

^ See de Thévenot(1687), p. 68–69 and p. 259

^ Late Ottoman cases in 1830s Balkans, i) Some five case reported 1833, M***r (1833) p. 440–41 columns 2 ii) 1834, Two such corpses, close to the village Paracini in the vicinity of Jagodina, see: Burgess (1835) p. 275 iii) Rarity of such cases in the 1830s,Goodrich (1836)p. 308 1835, Retaliative cycle Turkish authorities relative Kurdish "robbers", Slade (1837) p. 191

^ Stephen Massett

^ Massett (1863), p. 88–89

^ Layard (1871), p. 307

^ Ranft (1769), p. 345

^ missing

^ "Aiolos (2004)"

^ Dumas (2008), volume 8, chapter 3

^ Hughes (1820) p. 454, see also, on roasting incident: Holland (1815) p. 194

^ J.W.A.Streit, Constantinopel im Jahr 1821, oder Darstellung der blutigen und höchst schauderhaften Begebenheiten ... Leipzig, 1822, pp. 30, 31, 42–45. Cited by Kyriakos Simopoulos, "How Foreigners saw the Greece of the 1821 Revolution", Athens, 2004 (5th edition), vol. 1, pp. 153, 154, in Greek language.

^ Pouqueville Fr., Histoire de la régénération de la Grèce, Paris, 1825, vol. 2, p. 580

^ Makrygiannis Yannis, Memoirs, p. 27. (In Greek language) Yannis Makrygiannis (1797–1864) was a general and politician, hero of the Greek Revolution.

^ Paroulakis (1984)

^ Turkish reprisals on Greek War of independence, i) 2.June 1821, 10 Greeks at Bucharest, Fick (1821) p. 254 ii) During the massacre at Crete around 24 June 1821, most are said to have been impaled: Siegman (1821) p. 988, column 1 iii) 36 Greek hostages, including 7 bishops at onset of Siege of Tripolitsa Colburn (1821) p. 56 iv) In conjunction with the Chios Massacre in 1822, several Chiote merchants were detained and executed at Constantinople, 6 of whom were impaled alive: Hughes (1822)p. 169 v) Omer Vrioni organizing in 1821 Greek hunts where civilians were, at least in one instance, impaled on his orders.Waddington (1825) p. 52–54 vi) In early 1822 Cassandreia, some 300 civilians massacred, several reported to have been impaled, Grund (1822) p. 4 vii) During the last Siege of Missolonghi, in 1826, the Ottoman besiegers offered opportunity for capitulation for the besieged, while they also sent a message of consequences for refusal by impaling alive a priest, two women and several children in front of the line. The offer of capitulation was declined by the besieged Greeks. Alison(1856), p. 206

^ George Waddington, "A visit to Greece in 1823 and 1824", 2nd ed., London, 1825, p. 52

^ 20-50 "daily" brought in, most impaled Urban (1810) p. 74

^ Sowards (2009) The Serbian Revolution and the Serbian State

^ Obituary James Reid

^ Reid (2000), p. 441

^ "Sees Bolshevism as Hideous Religion", The New York Times, August 2, 1920

^ Erish (2012) p. 212

^ Shahbaz (1918), p. 142

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Impalement. |

Bibliography

- Books

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Alison, Archibald (1856). History of Europe from the fall of Napoleon in MDCCCXV to the accession of Louis Napoleon in MDCCCLII, volume 3. Edinburgh and London: W.Blackwood and Sons.

Andric, Ivo (1977). The Bridge on the Drina. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-02045-2.

d'Arvieux, Laurent; Labat, Jean B. (1755). Des Herrn von Arvieux ... hinterlassene merkwürdige Nachrichten. 5–6. Copenhagen and Leipzig: J.B. Ackermann.

Bastian, Adolf (1860). Der Mensch in der Geschichte. 3. Leipzig: Otto Wigand.

Beer, Johann C. (1713). Der durchleuchtigsten Erzherzogen zu Oesterreich Leben, Regierung und Großthaten. Nuremberg: Martin Endter.

Blount, Henry (1636). A Voyage into the Levant. London: Andrew Crooke.

Bond, Edward A. (editor); Horsey, Jerome; Fletcher, Giles (1856). Russia at the close of the sixteenth century. New York: Hakluyt Society (Burt Franklin reprint).CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Boyde, Henry (1736). Several voyages to Barbary. London: O. Payne.

Braithwaite, John (1729). The history of the revolutions in the empire of Morocco. London: Knapton and Betterworth.

Bryce, Trevor (2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921872-1.

von Buchenbach, Hans J. B. (1612). Orientalische Reyß deß edlen unnd vesten, Hanß Jacob Breüning, von und zu Buochenbach. Strassburg: Johann Carolo.

Burgess, Richard (1835). Greece and the Levant. 2. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

Callaway, Joseph A. (1995). Faces of the Old Testament. Macon, Georgia: Smyth & Helwys Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-880837-56-6.

Clarke, Adam (1831). The Holy Bible.. with a Commentary and Critical Notes. J. Emory and B. Waugh.

Crouch, C.L. (2009). War and Ethics in the Ancient Near East. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022352-1.

Dampier, William (1729). A Collection Of Voyages. 2. London: Knapton.

Daschitsky, Georg (1570). Erschreckliche Zeytunge von zweyen Mördern, mit namen Merten Farkaß, und Paul Wasansky. Prague: Georg Daschitsky.

Döpler, Jacob (1697). Theatrum Poenarum. 2. Leipzig: Friedrich Lanckishen Erben.

Dumas, Alexandre (2008). Celebrated Crimes Ali Pacha. Arc Manor.

Ehrlich, Anna (2005). Auf den Spuren der Josefine Mutzenbacher. Amalthea. ISBN 9783850025263.

Ehrlich, Paul R.; Ehrlich, Anne H. (2004). One With Nineveh. Washington DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-879-1.

Elias, Ney (editor); Ross, Edward D. (translator) (2009 (1898)). The Tarikh-i-rashidi. Srinagar Kashmir: Karakorum Books. Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Engel, Evamaria; Jacob, Frank-Dietrich (2006). Städtisches Leben im Mittelalter. Köln, Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 978-3-412-20205-7.

Ephʿal, Israel (2009). Ke-ʻir Netsurah. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17410-8.

Erish, Andrew A. (2012). Col. William N. Selig, the Man Who Invented Hollywood. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292742697.

Fick, Conrad F. (1867). Kleine Mittheilungen aus Kiel's Vergangenheit. Kiel: Carl Schröder&Comp.

Florescu, Radu R. (1999). Essays on Romanian History. The Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 973-9432-03-4.

Gadd, C.J. (1965). The Cambridge Ancient History: Assyria and Babylon, c. 1370–1300 B.C. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-00-134579-6.

Goodrich, C.A. (1836). The universal traveller. Hartford: Canfield & Robins.

Gottfried, Johann L. (1633). Grundliche und warhaffte Beschreibung de Konigreichs Schweden und dessen incorporirten Provintzen. Frankfurt am Main: Friedrich van Hulsius.

Green, Philip J.; Green, R.L. (1827). Sketches of the war in Greece. London: Thomas Hurst and Co.

Guer, Jean-Antoine (1747). Moeurs et usages des Turcs. 2. Paris: Coustelier.

Gutknecht, Jobst (1521). Von dem Dracole Wayda, dem großen Tyrannen. Nuremberg: Jobst Gutknecht.

Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-96556-6.

Han, Paul C.B. (1669). Venediger Löwen-Muth Und Türckischer Ubermuth. Hoffmann.

Hartmann, Johann M.; Büsching, Anton F. (1799). Erdbeschreibung und Geschichte von Afrika. 1, 12. Hamburg: Bohn.

Herrenschmidt, Clarisse; Bottéro, Jean (2000). Ancestor of the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226067162.

His, Rudoulf (1967) [1928]. Geschichte des deutschen Strafrechts bis zur Karolina (Reprint ed.). Oldenbourg. ASIN B0000BRMK3.

Holland, Henry (1815). Travels in the Ionian Isles, Albania, Thessaly, Macedonia. 1. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Hueber, Fortunatus (1693). Stammenbuch... Munich: Joh. Jäcklin.

Hughes, Thomas S. (1820). Travels in Sicily, Greece & Albania. 1. London: J. Mawman.

von Imhoff, Andrea L. (1736). Neu-Eroffneter Historien-Saal. 4. Basel: Johann Brandmüller.

Kern, Paul B. (1999). Ancient siege warfare. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33546-3.

Koch, Johann C. (1824). Hals- oder peinliche Gerichtsordnung Kaiser Carls V. Marburg: Krieger.

Koller, Markus (2004). Bosnien an der Schwelle zur Neuzeit. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 978-3-486-57639-9.

Korabinsky, Johann M. (1786). Geographisch-historisches und Produkten-Lexikon von Ungarn. Pressburg: Weber u. Korabinsky.

Kuhrt, Amelie (1995). The Ancient Near East. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

de La Motraye, Aubry (1723). A. de La Motraye's Travels. 1. London: Printed for the Author.

Layard, Austen H (1850). Nineveh and its remains. 1. London: Murray.

Layard, Austen H (1871). Discoveries among the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. New York: Harper & brothers.

von Loen, Johann M. (1751). Des Herrn von Loen Entwurf einer Staats-Kunst. Frankfurt, Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Fleischer.

Massett, Stephen (1863). Drifting about. New York: Carleton.

Mentzel, O.F.; Allemann, R.F.; Greenlees, Margaret (tr.) (1919). Life at the Cape in Mid-eighteenth Century: Being the Biography of Rudolf Siegfried Allemann. Van Riebeeck Society. ISBN 9780958452250.

Merry, Bruce (2004). Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0.

Morgan, Joseph (1729). A Complete History of Algiers. 2. London: Bettenham.

Moryson, Fynes; Hadfield, Andrew (2001). "Fynes Moryson, An Itinerary (1617)". Amazons, Savages, and Machiavels. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 166–179. ISBN 9780198711865.

Muir, Edward (1997). Ritual in early modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40967-4.

Mundy, Peter; Temple, Richard (editor) (1907). The travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608–1667. 1. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Osborne, Thomas (1745). A Collection of Voyages and Travels. London: Thomas Osborne.

Osenbrüggen, Eduard (1868). Studien zur deutschen und schweizerischen Rechtsgeschichte. Schaffhausen: F. Hurter.

de Pages, P.M.F (1791). Travels Round the World. London: J. Murray.

Paroulakis, Peter H. (1984). The Greeks: Their Struggle for Independence. Hellenic International Press. ISBN 0-9590894-0-3.

Pears, Edwin (2004). The Destruction of the Greek Empire And the Story of the Capture of Constantinople by the Turks. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-4776-8.

Philippides, Marios; Hanak, Walter K. (2011). The Siege and the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-1064-5.

Raymond, André (2000). Cairo. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00316-3.

Reid, James R. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire. Stuttgart: Steiner. ISBN 3-515-07687-5.

Richardson, Seth; Laneri, Nicola (2007). "Death and dismemberment in Mesopotamia". Performing Death. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 9781885923509.

Roch, Heinrich (1687). Neue Lausitz'sche Böhm-und Schlesische Chronica. Torgau: Johann Herbordt Klossen.

Runciman, Steven (1965). The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39832-9.

Russell, Alexander (1794). The Natural History of Aleppo. 1. London: Robinson.

St. Clair, William (2008 (revised edition, original from 1972)). That Greece Might Still Be Free. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-906924-00-3. Check date values in:|year=(help)

Schroeder, Otto (1920). Keilschrifttexte aus Assur verschiedenen Inhalts. Leipzig: Hinrich.

Schwab, Gustav (1827). Der Bodensee nebst dem Rheinthale von St Luziensteig bis Rheinegg. Stuttgart, Tübingen: Cotta.

Schweigger, Salomon (1613). Ein newe Reißbeschreibung auß Teutschland. Nuremberg: Katharina Lantzenbergerin.

Shahbaz, Yonan (1918). The rage of Islam. Philadelphia, Boston: Roger Williams Press.

Shaw, Thomas (1757). Travels, or Observations relating to several parts of Barbary and the Levant. London: Millar and Sandby.

Shepherd, William (1814). Paris, in eighteen hundred and two, and eighteen hundred and fourteen. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Slade, Adolphus (1837). Turkey, Greece and Malta. 2. London: Saunders and Otley.

Stavorinus, J.S.; Wilcocke, Samuel H. (tr.) (1798). Voyages to the East-Indies. 1. London: G.G. and J. Robinson.

Stedman, John Gabriel (1813). Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. 1. London: Johnson and Payne.

Stevens, J. (1711). A new collection of voyages and travels. 2. London: Knapton and Bell.

Taube, Friedrich Wilhelm von (1777). Historische und geographische Beschreibung des Königreiches Slavonien und des Herzogthumes Syrmien. 2. Leipzig.

Tetlow, Elisabeth M. (2004). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society. 1. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5.

de Thévenot, Jean; Lovell, Archibald (1687). The Travels Of Monsieur De Thevenot Into The Levant. 1. London: Faithorne.

de Tournefort, Joseph Pitton; Ozell, John (tr.) (1741). A Voyage Into the Levant. 1. London: D. Midwinter.

von Troilo, Franz Ferdinand (1676). Orientalische Reise-Beschreibung. Dresden: Bergen.

Ussishkin, David; Amit, Yairah (2006). "Sennacherib's Campaign to Philistia and Judah: Ekron, Lachish, and Jerusalem". Essays on Ancient Israel in Its Near Eastern Context: A Tribute to Nadav Naʼaman. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-128-3.

Vaporis, Nomikos M. (2000). Witnesses for Christ. Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881411966.

di Varthema, Ludovica; Jones, John W. (tr.) (1863). The Travels of Ludovico Di Varthema. London: Hakluyt Society.

Vehse, Karl E.; Demmler, Franz (tr.) (1856). Memoirs of the Court, Aristocracy, and Diplomacy of Austria. 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

Waddington, George (1825). A Visit to Greece, in 1823 and 1824. London: Murray.

Wiltenburg, Joy (2012). Crime and Culture in Early Modern Germany. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813933023.

Wagner, Johann C. (1687). Christlich- und Türckischer Staedt- und Geschicht-Spiegel. Augsburg: Jacob Kopppmayer.

Woltersdorf (1812). Die illyrischen provinzen und ihre einwohner. Vienna: Camesinaschen buchh.

- Newspapers, magazines and periodicals

Colburn and co (February 1822). "Political Events-Foreign". The New Monthly Magazine. London: Colburn and co. 6: 55–56.

Constable (September 1821). Foreign Intelligence.Turkey. The Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany. 88. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable. pp. 274–275.

Engelmann (1834). Leopold von Ledebur, ed. Geschichte und Verfassung des Cröverreiches (part 2). Allgemeines Archiv für die Geschichtskunde des Preußischen Staates. 14. Berlin: E.S. Mittler. pp. 140–165.

Fick, D.H (26 June 1821). Triumph, das Kreuz siegt!. Erlanger Real-Zeitung. 52. Erlangen: G.L.A.Gross. pp. 233–235.

Grund (26 February 1822). Türkisch-Griechische Angelegenheiten. Staats und gelehrte zeitung des hamburgischen unpartheyischen correspondenten. 33. Hamburg: Grundschen Erben. p. 4.

Haupt, Paul (January 1908). "Critical Notes on Esther". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 24, 2: 97–186. ISSN 1062-0516. JSTOR 527925.

Hughes, Thomas S. (1822). An Address to the people of England in the CAUSE OF THE GREEKS. The Pamphleteer. 21. London: A.J. Valpy. pp. 167–188.

Jastrow Jr., Morris (1921). "An Assyrian Law Code". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Baltimore: American Oriental Society. 41: 1–59. doi:10.2307/593702. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 593702.

M***r, G. (November 1833). "An Incursion into Turkey". The Metropolitan Magazine. New Haven: Peck and Newton: 439–442.

Mannheimer Zeitung (27 December 1784). "Wien, den 15. Christm". Mannheimer Zeitung. Mannheim. 156: 637–638.

Mayer, Werner (ed.) (2005). Orientalia, Vol.74, Fasc. 1. Rome, Italy: The Pontifical Biblical Institute.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

von Meyer von Knonau, Gerold (July 1855). Unzuchtstrafen im Mittelalter. Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit, Neue Folge. 2, 7. Nuremberg: Germanisches Museum. p. 175.

Olmstead, Albert Ten Eyck (February 1918). "Assyrian Government of Dependencies". The American Political Science Review. American Political Science Association. 12, 1: 63–77. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1946342.

Olmstead, Albert Ten Eyck (1921). "Shalmaneser III and the Establishment of the Assyrian Power". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Baltimore: American Oriental Society. 41: 345–82. doi:10.2307/593746. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 593702.

Presbyterian Magazine (January 1847). Massacre of the Nestorian Christians. The United Presbyterian magazine. 1. Edinburgh: Oliphant and sons. pp. 33–34.

Purser (1 December 1827). "A Turkish Execution". The Casket. London: Cowie and Strange and co. 1, 47: 337–339.

Ranft, Michael (1769). Von den Türkischen und andern Orientalischen Begebenheiten 1767. Fortgesetzte neue genealogisch-historische Nachrichten von den vornehmsten Begebenheiten, welche sich an den europäischen Höfen zugetragen. 89. Leipzig: Heinsius. pp. 342–352.

Schwetschke, J.C. (1789). Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, Volumes 1-3. Jena: C.A. Schwetschke.

Siegman, E.J. (ed) (4 September 1821). "Türkei". Allgemeine Zeitung, mit allerhöchste Privilegien. Cotta'shen Buch. 247: 987–988.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Urban, Sylvanus (pseud) (January 1810). Sylvanus Urban (pseud.), ed. Abstract of foreign Occurnces.Turkey. Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle. 80.1. London: Nichols and Son. pp. 74–75.

- Web resources

Aiolos (2004). "Turkish Culture: The Art of Impalement". Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-01-13.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

Axinte, Adrian. "Dracula: Between myth and reality". Stanford University. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Bible, ESV (2012). "Book of Esther 5, English Standard Version". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Bible, NIRV (2012). "Book of Esther 5, New International Readers' Version". Biblica.com. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Harper, Robert Francis, translator (1904). "The Code of Hammurabi". Retrieved 2013-03-01.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

Shaw, Benjamin (2012). "Was Haman Hanged or Impaled?". ligonier.org. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Sowards, Steven W. (2009). "The Serbian Revolution and the Serbian State". Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism). Michigan State University Libraries. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

WW2, People's War (2005). "Japanese torture techniques". BBC. Retrieved 2013-03-01.