Tres (instrument)

Cuban tres | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Tres guitar, tres cubano |

| Classification | String instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed | Cuba |

| Related instruments | |

Spanish guitar, laúd, tiple, bandola, cuatro | |

The tres (Spanish for three) is a guitar-like three-course chordophone of Cuban origin.[1] The most widespread variety of the instrument is the original Cuban tres with six strings. Its sound has become a defining characteristic of the Cuban son and it is commonly played in a variety of Afro-Cuban genres. In the 1930s the instrument was adapted into the Puerto Rican tres, which has nine strings and a body similar to that of the cuatro.

Contents

1 Cuba

2 Puerto Rico

3 Guajeo

3.1 Nengón

3.2 Kiribá

3.3 Changüí

3.4 Son

4 Solo

5 Notable players

6 See also

7 References

8 Further reading

Cuba

By most accounts, the tres was first used in several related Afro-Cuban musical genres originating in Eastern Cuba: the nengón, kiribá, changüí, and son. Benjamin Lapidus states: "The tres holds a position of great importance not only in changüí, but in the musical culture of Cuba as a whole."[2] One theory holds that initially, a guitar, tiple or bandola, was used in the son. They were eventually replaced by a new native-born instrument, a fusion of all three, called the tres. Helio Orovio writes that in 1892, Nené Manfugás brought the tres from Baracoa, its place of origin, to Santiago de Cuba.[3]Fernando Ortíz asserts a contrary theory that the tres is not actually a Cuban invention at all, but an instrument that had already existed in precolonial-era Spain.[4] A musician who plays the Cuban tres is called a tresero. There are variants of the instrument in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.[5]

The Cuban tres has three courses (groups) of two strings each for a total of six strings. From the low pitch to the highest, the principal tuning is in one of two variants in C Major, either: G4 G3, C4 C4, E4 E4 (top course in unisons), or more traditionally: G4 G3, C4 C4, E3 E4 (top course in octaves). Note that when the octave tuning is used, the order of the octaves in the first course is the reverse of the order in the third course (low-high versus high-low).[6] Today many treseros tune the whole instrument a step higher (in D major): A4 A3, D4 D4, F#4 F#4 or A4 A3, D4 D4, F#3 F#4.

Cuban trova singer, songwriter and guitarist Compay Segundo invented a variant of the tres and the Spanish guitar known as armónico.[7]

Puerto Rico

The Septeto Puerto Rico in the early 1930s. Guillermo "Piliche" Ayala is standing on the right with the first known Puerto Rican tres.

The Puerto Rican tres is an adaptation of Cuban tres. Investigators agree that the creation of the instrument was probably caused by the 1929 visit of Isaac Oviedo to Puerto Rico during a tour by the Septeto Matancero. Inspired by Oviedo, guitarist Guillero "Piliche" Ayala ordered the construction of a similar instrument for which the body of a cuatro was used.[8] As a result, the Puerto Rican tres is shaped like a Puerto Rican cuatro, with cut-outs, unlike the Cuban variety, which has a guitar-like shape. By 1934 the Puerto Rican cuatro had reached New York and nowadays most Puerto Rican tres players specialize in their national adaptation of the instrument, a notable exception being Nelson González. The Puerto Rican tres has 9 strings in 3 courses and is tuned G4 G3 G4, C4 C4 C4, E4 E3 E4. Players of the Puerto Rican tres are called tresistas.

Guajeo

The typical tres ostinato is the guajeo. It emerged in Cuba in the 19th century in the musical genres nengón, kiribá, changüí, and son.[9] The tres playing technique of changüí, and to a lesser extent nengón, has influenced contemporary son musicians, most notably pianist Lilí Martínez and tresero Pancho Amat, both of whom learned the style from Chito Latamblé.[10][11]

Nengón

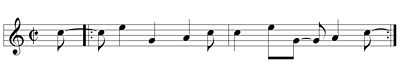

Benjamin Lapidus presents evidence of the "linear view of the son's development from nengón to kiribá and other regional styles, to changüí, and ultimately to son."[12] The nengón has a limited harmonic range, where the tonic and dominant are accentuated, and the tres is usually placed in the traditional octave tuning (G4 G3, C4 C4, E3 E4). The following nengón guajeo is an embellishment of the rhythmic figure known as tresillo.

Nengón guajeo written in cut-time.

Kiribá

Closely related to nengón, the kiribá style emerged in the Baracoa region of eastern Cuba.[13] According to musicologist Olavo Alén Rodríguez, the current thinking in Cuba discards kiribá as a distinct style since research has only found evidence of one song in that style. It was aptly named, "Kiribá".[14]

An example of an ensemble playing kiribá.

Changüí

When playing changüí, the tres is again usually given the traditional octave tuning. The following changüí tres guajeo consists of all offbeats.[15]

Changüí offbeat guajeo written in cut-time (

Son

According to Kevin Moore "there are two types of pure son tres guajeos: generic and song-specific. Song-specific guajeos are usually based on the song's melody, while the generic type involves simply arpeggiating triads."[16] The rhythmic pattern of the following "generic" guajeo is used in many songs. Note that the first measure consists of all offbeats. The figure can begin in the first measure, or the second measure, depending upon the structure of the song.

Generic son-based guajeo written in cut-time.

Solo

Isaac Oviedo playing his tres, c. 1930.

Tres solos were first constructed by grouping guajeo variations together, a melodic/rhythmic approach relying on subtle variation and repetition, that maintains a "groove" for dancers. According to Lapidus, tres solos in changüí typically sound "melodic/rhythmic ideas twice before moving on. This technique allows the soloist to set up a series of expectations for the listener, which are alternately satisfied, circumvented, frustrated, or inverted. The practice has its analogue in what Paul Berliner labels 'a community of ideas,' as motives from these sequences are frequently returned to throughout the course of any given solo."[17]

By the mid twentieth century, tres solos began incorporating the rhythmic "vocabulary" of quinto, the lead drum of rumba.[18] The counter-metric emphasis of quinto-based phrases break free from the confines of the guajeo, which is normally "locked" to the clave cycle. Thus, quinto-based solos are capable of creating long cycles of tension—release spanning many measures.

Notable players

The following are some of the most influential performers of the Cuban tres.[19][20][21]

- Efraín Amador

- Pancho Amat

- Félix Cárdenas

- Juan de la Cruz "Cotó" Antomarchi

- Carlos Godínez

- Nelson González

- Chito Latamblé

Nené Manfugás (es)- Juanito Márquez

- Isaac Oviedo

- Papi Oviedo

- Efraín Ríos

- Niño Rivera

- Arsenio Rodríguez

- Charlie Rodríguez

- Eliseo Silveira

- Panchito Solares

Senén Suárez (es)

Notable performers of the Puerto Rican tres include:[21]

- Guillermo "Piliche" Ayala

- Mario Hernández

- Luis "Lija" Ortiz

- Biriquín Rivera

- Máximo Torres

See also

- Stringed instrument tunings

References

^ The Stringed Instrument Database

^ Lapidus, Benjamin (2008). Origins of Cuban Music and Dance: Changüí. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. p. 16..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Orovio, Helio (La Habana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, [1981] 1992). Diccionario de la Musica Cubana. p. 481.

^ Ortíz, Fernando (1952-1955) Los instrumentos de la musica afrocubana v. 2 p. 313.

^ Lapidus (2008). p. 18.

^ Pena, Joel (2007). Fun with Cuban Tres. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay.

ISBN 978-0-7866-7292-9.

^ Betancourt Molina, Lino (3 April 2013). "El armónico de Compay Segundo". Cubarte (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 April 2016.

^ Gómez, Ramón. "El vínculo del tres cubano y el tres puertorriqueño". Proyecto del Cuatro Puertorriqueño (in Spanish). Retrieved February 4, 2016.

^ Lapidus (2008). p. 16-18.

^ Shepherd, John; Horn, David (2014). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume 9. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 535.

^ Lapidus (2008). p. 51.

^ Lapidus (2008). p. 96.

^ González, Leonel "Guajiro"; Griffin, Jon (2012). Cuban Masters Series: The Cuban Tres. US: Salsa Blanca Publishing. p. 535.

^ From an interview with Jon Griffin, Havana, Cuba, 2013.

^ Moore, Kevin (2010). Beyond Salsa Piano; The Cuban Timba Piano Revolution v.1 The Roots of Timba Tumbao p. 17. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com.

^ Moore, Kevin (2010). Beyond Salsa Piano v.1 p. 32. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com.

ISBN 1439265844.

^ Lapidus (2008). p. 56.

^ Peñalosa, David (2011) Rumba Quinto. p. xiv. Redway, CA: Bembe Books.

ISBN 1-4537-1313-1

^ Amador, Efraín (2005). Universalidad del laúd y el tres cubano (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 10.

^ Giro, Radamés (1997). Visión panorámica de la guitarra en Cuba (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 51.

^ ab González, Nelson (2006). Tres Guitar Method. Pacific, MO: Mel Bay. pp. 3–4.

Further reading

- Books

Richards, Tobe A. (2007). The Tres Cubano Chord Dictionary: C Major Tuning 648 Chords. United Kingdom: Cabot Books. ISBN 978-1-906207-03-8. — A comprehensive chord dictionary instructional guide.

Richards, Tobe A. (2007). The Tres Cubano Chord Dictionary: D Major Tuning 648 Chords. United Kingdom: Cabot Books. ISBN 978-1-906207-04-5. — A comprehensive chord dictionary instructional guide.

Griffin, Jon (2007). El tres cubano. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-8256-3324-9. — An instructional guide (in Spanish and English)

- Online resources

The Tres in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican Cuatro Project.- Burns, Sheila (19 May 2009). Havana: The Music of the Cricket. The Guardian.

- Echarry, Irina (7 May 2009) Tres Magic on Havana’s Malecon . Havana Times.

- Griffin, Jon. Cuban Tres - The 3 String Guitar Instrument from Cuba. Salsa Blanca.