George N. Briggs

George Nixon Briggs | |

|---|---|

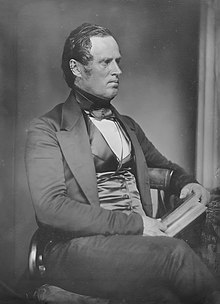

Portrait by Southworth & Hawes, c. 1848 | |

| 19th Governor of Massachusetts | |

In office January 9, 1844 – January 11, 1851 | |

| Lieutenant | John Reed, Jr. |

| Preceded by | Marcus Morton |

| Succeeded by | George S. Boutwell |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts | |

In office March 4, 1831 – March 3, 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Henry W. Dwight (9th) George Grennell Jr. (7th) |

| Succeeded by | William Jackson (9th) Julius Rockwell (7th) |

| Constituency | 9th district (1831–33) 7th district (1833–43) |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1796-04-12)April 12, 1796 Adams, Massachusetts |

| Died | September 12, 1861(1861-09-12) (aged 65) Pittsfield, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse(s) | Harriet Briggs |

| Children | Harriet Briggs George Briggs Henry Shaw Briggs |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

George Nixon Briggs (April 12, 1796 – September 12, 1861) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts. A Whig, Briggs served for twelve years in the United States House of Representatives, and served seven one-year terms as the 19th Governor of Massachusetts, from 1844 to 1851.

Raised in rural Upstate New York, Briggs studied law in western Massachusetts, where his civic involvement and successful legal practice preceded statewide political activity. He was elected to Congress in 1830, where he supported the conservative Whig agenda, serving on the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads. He was also a regular advocate of temperance, abstaining from all alcohol consumption.

He was nominated by the Whigs in 1843 to run against Democratic Governor Marcus Morton as part of a Whig bid for more rural votes, and easily won election until 1849. Although he sought to avoid the contentious issue of slavery, he protested South Carolina policy allowing the imprisonment of free African Americans. He supported capital punishment, notably refusing to commute the death sentence of John White Webster for the murder of George Parkman. Briggs died of an accidental gunshot wound at his home in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 U.S. House of Representatives

3 Governor of Massachusetts

4 Later years

5 Notes

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Early life and education

Briggs' birthplace

George Nixon Briggs was born in Adams, Massachusetts on April 12, 1796. He was the eleventh of twelve children of Allen Briggs, a blacksmith originally from Cranston, Rhode Island, and Nancy (Brown) Briggs, of Huguenot descent.[1] His parents moved the family to Manchester, Vermont when he was seven, and, two years later, to White Creek, New York.[2] The household was religious: his father was a Baptist and his mother was a Quaker, and they gave their children religious instruction from the Bible.[3]

At the age of 14, during the Second Great Awakening, which was especially strong in Upstate New York, Briggs experienced a conversion experience and joined the Baptist faith. He spoke at revival meetings of his experience, drawing appreciative applause from the crowds, according to Hiland Hall, who came to know Briggs at that time and who became a lifelong friend and political associate.[4] His faith informed his personal behavior: he remained committed to religious ideals, for instance objecting to Congressional sessions that stretched into Sunday and abstaining from alcohol consumption.[5][6]

Briggs sporadically attended the public schools in White Creek, and was apprenticed for three years to a Quaker hatter.[7] With support from his older brothers he embarked on the study of law in Pittsfield and Lanesboro in 1813, and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1818.[8] He first opened a practice in Adams, moved it to Lanesboro in 1823, and Pittsfield in 1842. His trial work was characterized by a contemporary as clear, brief, and methodical, even though he was fond of telling stories in less formal settings.[9]

In 1817 Briggs helped to establish a Baptist church in Lanesboro; in this congregation he met Harriet Hall, whom he married in 1818; their children were Harriet, George, and Henry.[10] Briggs was also called upon to raise the four orphaned children of his brother Rufus, one of the brothers who supported him in his law studies. Rufus died in 1816, followed by his wife not long afterward.[11]

Briggs' involvement in civic life began at the local level. From 1824 to 1831 Briggs was the register of deeds for the Northern district of Berkshire County, Massachusetts.[12] He was elected town clerk in 1824, was appointed chairman of the board of commissioners of highways in 1826.[13] His interest in politics was sparked by his acquaintance with Henry Shaw, who served in the United States House of Representatives from 1817 to 1821.[14]

A criminal case tried in 1826 brought Briggs wider notice. An Oneida Indian living in Stockbridge was accused of murder. Briggs was appointed by the court to defend him; convinced by the evidence that the man was innocent, Briggs made what was described by a contemporary as a plea that was "a model of jury eloquence". The jury, unfortunately, disagreed with Briggs, and convicted the man, who was hanged. In 1830 the true murderer confessed to commission of the crime.[15]

U.S. House of Representatives

Despite his rise in prominence, Briggs was at first ineligible for state offices because he did not own property. In 1830 he decided to run for Congress, for which there was no such requirement. He was elected to the twenty-second through the twenty-fourth Congresses as an Anti-Jacksonian, and as a Whig to the twenty-fifth through twenty-seventh Congresses, serving from March 4, 1831 to March 3, 1843. He decided not to run for reelection in 1842.[16]

Hiland Hall of Vermont was a longtime friend and Congressional colleague.

Briggs was what became known in later years as a "Cotton Whig". He was in favor of protectionist tariffs, and opposed the expansion of slavery into western territories, but did not seek to threaten the unity of the nation with a strong stance against slavery. He served on the Committee on Public Expenditures and the Committee on the Post Office and Post Roads, serving for a time as the chairman of each.[16] The Post Office committee was a regular recipient of complaints from southern states concerning the transmission of abolitionist mailings, which were seen there as incendiary; the matter was of some controversy because southern legislators sought to have these types of mailings banned. Briggs' friend Hiland Hall, who also sat on the committee, drafted a report in 1836 rebutting the rationales used in such legislative proposals, but the committee as a whole, and then the House, refused to accept the report.[17] Although the authorship of the report appears to be entirely Hall's, Briggs may have contributed to it, and was a signatory to Hall's publication of the report in the National Intelligencer, a major political journal.[18] The document was influential in driving later Congressional debate on legislative proposals concerning abolitionist mailings, none of which were ever adopted.[19] Briggs and Hall were both instrumental in drafting and gaining passage of the Post Office Act of 1836, which included substantive accounting reforms in the wake of financial mismanagement by Postmaster General William Taylor Barry.[20]

During his time in Congress, Briggs was a vocal advocate for temperance. He formed the Congressional Temperance Society in 1833, sitting on its executive committee; at an 1836 temperance convention at Saratoga Springs, New York he advocated the taking of total abstinence pledges as a way to bring more people away from the evils of alcohol,[6] and notably prepared such a pledge for Kentucky Representative Thomas F. Marshall on the floor of the House of Representatives. His moves to organize the temperance movement in Congress died out when he left the body, but it was a cause he would continue to espouse for the rest of his life.[21] In 1860 he was chosen president of the American Temperance Union.[22]

During the winter of 1834–1835, while walking along the Washington Canal, he heard a crowd exclaim that a young black boy had fallen in and was drowning. Upon hearing this, he dove into the water without removing any of his clothes and saved the boy.[23]

Governor of Massachusetts

Marcus Morton, the incumbent governor, lost to Briggs in 1843.

Briggs was nominated to run for the governorship on the Whig ticket against the incumbent Democrat Marcus Morton in 1843.[24] Former Governor John Davis had been nominated first, but refused the nomination, possibly because Daniel Webster promised him party support for a future vice presidential bid. Briggs was apparently recommended as a compromise candidate acceptable to different factions within the party (one controlled by Webster, the other by Abbott Lawrence).[25] He was also probably chosen to appeal more directly to the state's rural voters, a constituency that normally supported Morton. The abolitionist Liberty Party also fielded a candidate, with the result that none of the candidates won the needed majority. The legislature decided the election in those cases; with a Whig majority there, Briggs' election was assured.[24] Briggs was reelected annually until 1850 against a succession of Democratic opponents. He won popular majorities until the 1849 election, even though third parties (including the Liberty Party and its successor, the Free Soil Party) were often involved.[26] Although Whigs had a reputation for aristocratic bearing, Briggs was much more a man of the people than the preceding Whig governors, John Davis and Edward Everett.[27]

In 1844 Briggs, alarmed at a recently enacted policy by South Carolina authorizing the imprisonment of free blacks arriving there from Massachusetts and other northern states, sent representatives to protest the policy. Samuel Hoar and his daughter Elizabeth were unsuccessful in changing South Carolina policy, and after protests against what was perceived as Yankee interference in Southern affairs, were advised to leave the state for their own safety.[28]

Capital punishment was a major issue that was debated in the state during Brigg's tenure, with social reformers calling for its abolition. Briggs personally favored capital punishment, but for political reasons called for moderation in its use, seeking, for example, to limit its application in murder cases to those involving first degree murder.[29] After an acquittal in an 1846 murder case where anti-death penalty sentiment was thought to have a role, Briggs, seeking to undercut the anti-death penalty lobby, proposed eliminating the penalty for all crimes except murder, but expressed concern that more such acquittals by sympathetic juries would undermine the connection between crime and punishment.[30]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

—Ralph Waldo Emerson[31]

Briggs' argument was used in the 1849 trial of Washington Goode, a black mariner accused of killing a rival for the affections of a lady. The case against Goode was essentially circumstantial, but the jury heeded the district attorney's call for assertive punishment of "crimes of violence" and convicted him.[32] There were calls for Briggs to commute Goode's capital sentence, but he refused, writing "A pardon here would tend toward the utter subversion of the law."[33]

Not long after the Goode case came the sensational trial of Professor John White Webster in the murder of George Parkman, a crime that took place at the Harvard Medical School in November 1849. The trial received nationwide coverage, and the prosecution case was based on evidence that was either circumstantial (complicated by the fact that a complete corpse was not found), or founded on new types of evidence (forensic dentistry was used for the first time in this trial).[34][35] Furthermore, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw was widely criticized for bias in the instructions he gave to the jury.[36] Briggs was petitioned to commute Webster's sentence by death penalty opponents, and even threatened with physical harm if he did not.[37] He refused however, stating that the evidence in the case was clear (especially after Webster gave a confession), and that there was no reason to doubt that the court had acted with due and proper diligence.[38]

During Briggs' time as governor, abolitionist activists continued to make inroads against both the Whigs and Democrats, primarily making common cause with the Democrats against the dominant Whigs.[39] Briggs' stance as a Cotton Whig put him in opposition to these forces. He opposed the Mexican–American War, but acceded to federal demands that the states assist in raising troops for the war, earning the wrath of activist Wendell Phillips. He did promote other types of reform, supporting Horace Mann in his activities to improve education in the state.[16]

George S. Boutwell, c. 1851 portrait by Southworth & Hawes

In 1849, Briggs failed to secure a majority in the popular vote because of the rise in power of the Free Soil Party, but the Whig legislature returned him to office.[40] In the 1850 election, anger over the Compromise of 1850 (a series of federal acts designed to preserve the unity of the nation which included the Fugitive Slave Act) prompted the Democrats and Free Soilers to form a coalition to gain control over the Massachusetts legislature, and divided the Whigs along pro- and antiabolition lines. With the gubernatorial election again sent to the legislature, Democrat George S. Boutwell was chosen over Briggs.[41]

Later years

Briggs resumed the practice of law in Pittsfield. He was a member of the state constitutional convention in 1853, and sat as a judge of the Court of Common Pleas from 1853 to 1858.[42] In 1859 he was nominated for governor by the fading Know-Nothing movement, but trailed far behind other candidates.[43]

In 1861 Briggs was appointed by President Abraham Lincoln to a diplomatic mission to the South American Republic of New Granada (roughly present-day Colombia and Panama). However, he died before he could take up the position.[16] On September 4, 1861[44] Briggs was getting an overcoat out of his closet at his home in Pittsfield, when a gun fell. As Briggs was picking it up, the gun discharged and Briggs was shot.[45] Briggs died early in the morning of September 12, 1861, and was buried in the Pittsfield Cemetery.[46]

Notes

^ Richards, p. 15

^ Richards, pp. 22–23

^ Richards, pp. 20, 26

^ Richards, pp. 27–28

^ Richards, p. 146

^ ab Burns, p. 412

^ Richards, pp. 33–34

^ Richards, pp. 39–63

^ History of Berkshire County, Volume 1, p. 346

^ Richards, pp. 51, 63, 159, 200

^ Richards, p. 40

^ History of Berkshire County, Volume 1, p. 303

^ Larson, p. 539

^ Whipple, p. 167

^ Whipple, p. 171

^ abcd Larson, p. 540

^ John (1997), p. 94

^ John (1997), pp. 94–96

^ John (1997), pp. 104–105

^ John (2009), pp. 244–248

^ Burns, p. 413

^ Burns, p. 414

^ Martin, Susan (August 11, 2016). ""Just Mede of Praise": George N. Briggs' Heroic Act". The Beehive. Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved August 11, 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Hart, p. 4:93

^ Dalzell, pp. 77–78

^ Hart, pp. 4:94–99

^ Formisano, p. 301

^ Petrulionis, pp. 385–418

^ Rogers, p. 84

^ Rogers, pp. 88–90

^ Formisano, p. 300

^ Rogers, pp. 90–91

^ Rogers, p. 93

^ Bowers, p. 22

^ Rogers, pp. 95–97

^ Rogers, pp. 99–103

^ Richards, p. 239

^ Richards, pp. 244–249

^ Holt, pp. 452–453, 579

^ Holt, p. 452

^ Holt, pp. 580–583

^ History of Berkshire County, Volume 1, p. 329

^ Mitchell, p. 128

^ Richards, p. 397

^ Richards, p. 398

^ Smith, p. 324

References

Bowers, C. Michael (2011). Forensic Dentistry Evidence: An Investigator's Handbook. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 9780123820013. OCLC 688636942.

Burns, James Dawson (1861). The Temperance Dictionary. London: Job Caudwell. OCLC 752754623.

Dalzell, Jr, Robert (1973). Daniel Webster and the Trial of American Nationalism, 1843–1852. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395139988.

Formisano, Ronald (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195035094. OCLC 18429354.

Hart, Albert Bushnell (ed) (1927). Commonwealth History of Massachusetts. New York: The States History Company. OCLC 1543273.CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link) (five volume history of Massachusetts until the early 20th century)

Holt, Michael (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195055443. OCLC 231788473.

History of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, Volume 1. New York: J. H. Beers & Co. 1885.

John, Richard (January 1997). "Hiland Hall's "Report on Incendiary Publications": A Forgotten Nineteenth Century Defense of the Constitutional Guarantee of the Freedom of the Press". The American Journal of Legal History. 41 (1): 94–125. JSTOR 845472.

John, Richard (2009) [1995]. Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674039148. OCLC 434587908.

Larson, Sylvia (1999). "Briggs, George Nixon". Dictionary of American National Biography. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 539–541. ISBN 9780195206357. OCLC 39182280.

Mitchell, Thomas (2007). Anti-Slavery Politics in Antebellum and Civil War America. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275991685. OCLC 263714377.

Petrulionis, Sandra Harbert (September 2001). ""Swelling That Great Tide of Humanity": The Concord, Massachusetts, Female Anti-Slavery Society". The New England Quarterly. 74 (3): 385–418. JSTOR 3185425.

Richards, William Carey (1867). Great in Goodness: A Memoir of George N. Briggs, Governor of The Commonwealth Of Massachusetts, From 1844 to 1851. Boston, MA: Gould and Lincoln. OCLC 4045699.

Rogers, Alan (2008). Murder and the Death Penalty in Massachusetts. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9781558496323. OCLC 137325169.

Smith, Joseph (1885). "Hon. George N. Briggs, LL. D". Memorial Biographies, 1845–1871: 1860–1862. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. OCLC 13166463.

Whipple, A. B (1896). "George N. Briggs". Collections of the Berkshire Historical and Scientific Society (Volume 2). OCLC 1772059.

Further reading

Giddings, Edward Jonathan (1890). American Christian Rulers. New York: Bromfield & Company. pp. 61–69. OCLC 5929456.

External links

- Congressional Biography of George Nixon Briggs

U.S. House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry W. Dwight | Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 9th congressional district 1831–1833 | Succeeded by William Jackson |

| Preceded by George Grennell, Jr. | Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 7th congressional district March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1843 | Succeeded by Julius Rockwell |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Marcus Morton | Governor of Massachusetts January 9, 1844 – January 11, 1851 | Succeeded by George S. Boutwell |