Reverse genetics

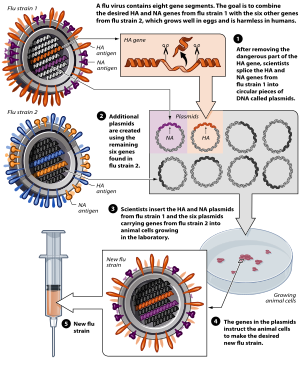

A diagram illustrating the process of Avian Flu vaccine development by Reverse Genetics techniques.

Reverse genetics is a method that is used to help understand the function of a gene by analyzing the phenotypic effects of specific engineered gene sequences.

Reverse genetics usually proceeds in the opposite direction of so-called forward genetic screens of classical genetics. In other words, while forward genetics seeks to find the genetic basis of a phenotype or trait, reverse genetics seeks to find what phenotypes arise as a result of particular genetic sequences.

Automated DNA sequencing generates large volumes of genomic sequence data relatively rapidly. Many genetic sequences are discovered in advance of other, less easily obtained, biological information. Reverse genetics attempts to connect a given genetic sequence with specific effects on the organism.[citation needed]

Contents

1 Techniques used

1.1 Directed deletions and point mutations

1.2 Gene silencing

1.3 Interference using transgenes

2 Vaccine synthesis

2.1 Influenza vaccine

2.2 Advantages and disadvantages

3 See also

4 References

5 External links

Techniques used

In order to learn the influence a sequence has on phenotype, or to discover its biological function, researchers can engineer a change or disrupt the DNA. After this change has been made a researcher can look for the effect of such alterations in the whole organism. There are several different methods of reverse genetics:

Directed deletions and point mutations

Site-directed mutagenesis is a sophisticated technique that can either change regulatory regions in the promoter of a gene or make subtle codon changes in the open reading frame to identify important amino residues for protein function.

Wild-type Physcomitrella patens (A) and Knockout mosses (B-D): Deviating phenotypes induced in gene-disruption library transformants. Physcomitrella wild-type and transformed plants were grown on minimal Knop medium to induce differentiation and development of gametophores. For each plant, an overview (upper row; scale bar corresponds to 1 mm) and a close-up (bottom row; scale bar equals 0.5 mm) are shown. A: Haploid wild-type moss plant completely covered with leafy gametophores and close-up of wild-type leaf. B–D: Different mutants.[1]

Alternatively, the technique can be used to create null alleles so that the gene is not functional. For example, deletion of a gene by gene targeting (gene knockout) can be done in some organisms, such as yeast, mice and moss. Unique among plants, in Physcomitrella patens, gene knockout via homologous recombination to create knockout moss (see figure) is nearly as efficient as in yeast.[2] In the case of the yeast model system directed deletions have been created in every non-essential gene in the yeast genome.[3] In the case of the plant model system huge mutant libraries have been created based on gene disruption constructs.[4] In gene knock-in, the endogenous exon is replaced by an altered sequence of interest.[5]

In some cases conditional alleles can be used so that the gene has normal function until the conditional allele is activated. This might entail 'knocking in' recombinase sites (such as lox or frt sites) that will cause a deletion at the gene of interest when a specific recombinase (such as CRE, FLP) is induced. Cre or Flp recombinases can be induced with chemical treatments, heat shock treatments or be restricted to a specific subset of tissues.

Another technique that can be used is TILLING. This is a method that combines a standard and efficient technique of mutagenesis with a chemical mutagen such as ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) with a sensitive DNA-screening technique that identifies point mutations in a target gene.

Gene silencing

The discovery of gene silencing using double stranded RNA, also known as RNA interference (RNAi), and the development of gene knockdown using Morpholino oligos, have made disrupting gene expression an accessible technique for many more investigators. This method is often referred to as a gene knockdown since the effects of these reagents are generally temporary, in contrast to gene knockouts which are permanent.

RNAi creates a specific knockout effect without actually mutating the DNA of interest. In C. elegans, RNAi has been used to systematically interfere with the expression of most genes in the genome. RNAi acts by directing cellular systems to degrade target messenger RNA (mRNA).

RNAi interference, specifically gene silencing, has become a useful tool to silence the expression of genes and identify and analyze their loss-of-function phenotype. When mutations occur in alleles, the function which it represents and encodes also is mutated and lost; this is generally called a loss-of-function mutation.[6] The ability to analyze the loss-of-function phenotype allows analysis of gene function when there is no access to mutant alleles.[7]

While RNA interference relies on cellular components for efficacy (e.g. the Dicer proteins, the RISC complex) a simple alternative for gene knockdown is Morpholino antisense oligos. Morpholinos bind and block access to the target mRNA without requiring the activity of cellular proteins and without necessarily accelerating mRNA degradation. Morpholinos are effective in systems ranging in complexity from cell-free translation in a test tube to in vivo studies in large animal models.

Interference using transgenes

A molecular genetic approach is the creation of transgenic organisms that overexpress a normal gene of interest. The resulting phenotype may reflect the normal function of the gene.

Alternatively it is possible to overexpress mutant forms of a gene that interfere with the normal (wildtype) gene's function. For example, over-expression of a mutant gene may result in high levels of a non-functional protein resulting in a dominant negative interaction with the wildtype protein. In this case the mutant version will out compete for the wildtype proteins partners resulting in a mutant phenotype.

Other mutant forms can result in a protein that is abnormally regulated and constitutively active ('on' all the time). This might be due to removing a regulatory domain or mutating a specific amino residue that is reversibly modified (by phosphorylation, methylation, or ubiquitination). Either change is critical for modulating protein function and often result in informative phenotypes.

Vaccine synthesis

Reverse genetics plays a large role in vaccine synthesis. Vaccines can be created by engineering novel genotypes of infectious viral strains which diminish their pathogenic potency enough to facilitate immunity in a host. The reverse genetics approach to vaccine synthesis utilizes known viral genetic sequences to create a desired phenotype: a virus with both a weakened pathological potency and a similarity to the current circulating virus strain. Reverse genetics provides a convenient approach to the traditional method of creating inactivated vaccines, viruses which have been killed using heat or other chemical methods.

Vaccines created through reverse genetics methods are known as attenuated vaccines, named because they contain weakened (attenuated) live viruses. Attenuated vaccines are created by combining genes from a novel or current virus strain with previously attenuated viruses of the same species.[8] Attenuated viruses are created by propagating a live virus under novel conditions, such as a chicken's egg. This produces a viral strain that is still live, but not pathogenic to humans,[9] as these viruses are rendered defective in that they cannot replicate their genome enough to propagate and sufficiently infect a host. However, the viral genes are still expressed in the host's cell through a single replication cycle, allowing for the development of an immunity.[10]

Influenza vaccine

A common way to create a vaccine using reverse genetic techniques is to utilize plasmids to synthesize attenuated viruses. This technique is most commonly used in the yearly production of influenza vaccines, where an eight plasmid system can rapidly produce an effective vaccine. The entire genome of the influenza A virus consists of eight RNA segments, so the combination of six attenuated viral cDNA plasmids with two wild-type plasmids allow for an attenuated vaccine strain to be constructed. For the development of influenza vaccines, the fourth and sixth RNA segments, encoding for the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins respectively, are taken from the circulating virus, while the other six segments are derived from a previously attenuated master strain. The HA and NA proteins exhibit high antigen variety, and therefore are taken from the current strain for which the vaccine is being produced to create a well matching vaccine.[8]

cDNA sequences of viral RNA are synthesized from attenuated master strains by using RT-PCR.[8] This cDNA can then be inserted between an RNA polymerase I (Pol I) promoter and terminator sequence. The cDNA and pol I sequence is then, in turn, surrounded by an RNA polymerase II (Pol II) promoter and a polyadenylation site.[11] This entire sequence is then inserted into a plasmid. Six plasmids derived from attenuated master strain cDNA are cotransfected into a target cell, often a chicken egg, alongside two plasmids of the currently circulating wild-type influenza strain. Inside the target cell, the two "stacked" Pol I and Pol II enzymes transcribe the viral cDNA to synthesize both negative-sense viral RNA and positive-sense mRNA, effectively creating an attenuated virus.[8] The result is a defective vaccine strain that is similar to the current virus strain, allowing a host to build immunity. This synthesized vaccine strain can then be used as a seed virus to create further vaccines.

Advantages and disadvantages

Vaccines engineered from reverse genetics carry several advantages over traditional vaccine designs. Most notably is speed of production. Due to the high antigenic variation in the HA and NA glycoproteins, a reverse-genetic approach allows for the necessary genotype (i.e. one containing HA and NA proteins taken from currently circulating virus strains) to be formulated rapidly.[8] Additionally, since the final product of a reverse genetics attenuated vaccine production is a live virus, a higher immunogenicity is exhibited than in traditional inactivated vaccines,[12] which must be killed using chemical procedures before being transferred as a vaccine. However, due to the live nature of attenuated viruses, complications may arise in immunodeficient patients.[13] There is also the possibility that a mutation in the virus could result the vaccine to turning back into a live unattenuated virus.[14]

See also

- Forward genetics

References

^ Egener et al. BMC Plant Biology 2002 2:6 doi:10.1186/1471-2229-2-6

^ Reski R (1998). "Physcomitrella and Arabidopsis: the David and Goliath of reverse genetics". Trends Plant Sci. 3 (6): 209–210. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01257-6..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. (August 1999). "Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis". Science. 285 (5429): 901–6. doi:10.1126/science.285.5429.901. PMID 10436161.

^ Schween G, Egener T, Fritzowsky D, Granado J, Guitton MC, Hartmann N, Hohe A, Holtorf H, Lang D, Lucht JM, Reinhard C, Rensing SA, Schlink K, Schulte J, Reski R (May 2005). "Large-scale analysis of 73 329 physcomitrella plants transformed with different gene disruption libraries: production parameters and mutant phenotypes". Plant Biology. 7 (3): 228–37. doi:10.1055/s-2005-837692. PMID 15912442.

^ Manis JP (December 2007). "Knock out, knock in, knock down--genetically manipulated mice and the Nobel Prize". The New England Journal of Medicine (PDF)|format=requires|url=(help). Massachusetts Medical Society. 357 (24): 2426–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0707712. OCLC 34945333. PMID 18077807.

^ McClean, Phillip. "Types of Mutations". Genes and Mutations. North Dakota State University. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

^ Lamour, Kurt; Tierney, Melinda. "An Introduction to Reverse Genetic Tools for Investigating Gene Function". APSnet. The American Phytopathological Society.

^ abcde Hoffmann, Erich; Krauss, Scott; Perez, Daniel; Webby, Richard; Webster, Robert (2002). "Eight-plasmid system for rapid generation of influenza virus vaccines" (PDF). Vaccine. 20: 3165–3170. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00268-2 – via Elsevier.

^ Badgett MR, Auer A, Carmichael LE, Parrish CR, Bull JJ (October 2002). "Evolutionary dynamics of viral attenuation". Journal of Virology. 76 (20): 10524–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.76.20.10524-10529.2002. PMC 136581. PMID 12239331.

^ Lauring AS, Jones JO, Andino R (June 2010). "Rationalizing the development of live attenuated virus vaccines". Nature Biotechnology. 28 (6): 573–9. doi:10.1038/nbt.1635. PMC 2883798. PMID 20531338.

^ Mostafa A, Kanrai P, Petersen H, Ibrahim S, Rautenschlein S, Pleschka S (2015-01-23). "Efficient generation of recombinant influenza A viruses employing a new approach to overcome the genetic instability of HA segments". PLoS One. 10 (1): e0116917. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116917. PMC 4304806. PMID 25615576.

^ Stobart CC, Moore ML (June 2014). "RNA virus reverse genetics and vaccine design". Viruses. 6 (7): 2531–50. doi:10.3390/v6072531. PMC 4113782. PMID 24967693.

^ "General Recommendations on Immunization". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

^ Shimizu H, Thorley B, Paladin FJ, Brussen KA, Stambos V, Yuen L, Utama A, Tano Y, Arita M, Yoshida H, Yoneyama T, Benegas A, Roesel S, Pallansch M, Kew O, Miyamura T (December 2004). "Circulation of type 1 vaccine-derived poliovirus in the Philippines in 2001". Journal of Virology. 78 (24): 13512–21. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.24.13512-13521.2004. PMC 533948. PMID 15564462.

External links

Library resources about Reverse genetics |

|

- From the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) site:

- Reassortment vs. Reverse Genetics

- Reverse Genetics: Building Flu Vaccines Piece by Piece

- From the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) site:

Neumann G, Hatta M, Kawaoka Y (2003). "Reverse genetics for the control of avian influenza". Avian Diseases. 47 (3 Suppl): 882–7. doi:10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.882. PMID 14575081.

Neumann G, Fujii K, Kino Y, Kawaoka Y (November 2005). "An improved reverse genetics system for influenza A virus generation and its implications for vaccine production". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (46): 16825–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505587102. PMC 1283806. PMID 16267134.

Ozaki H, Govorkova EA, Li C, Xiong X, Webster RG, Webby RJ (February 2004). "Generation of high-yielding influenza A viruses in African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells by reverse genetics". Journal of Virology. 78 (4): 1851–7. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.4.1851-1857.2004. PMC 369478. PMID 14747549.