Sudetenland

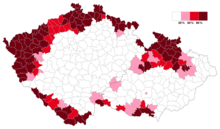

The native German-speaking regions in 1930, within the borders of the current Czech Republic, which in the interwar period were referred to as the Sudetenland

The context of German-speaking Europe circa 1937

The Sudetenland (/suːˈdeɪtənlænd/ (![]() listen); German: [zuˈdeːtn̩ˌlant]; Czech and Slovak: Sudety; Polish: Kraj Sudecki) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia from the time of the Austrian Empire.

listen); German: [zuˈdeːtn̩ˌlant]; Czech and Slovak: Sudety; Polish: Kraj Sudecki) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia from the time of the Austrian Empire.

The word "Sudetenland" did not come into being until the early part of the 20th century and did not come to prominence until over a decade into the century, after the First World War, when the German-dominated Austria-Hungary was dismembered and the Sudeten Germans found themselves living in the new country of Czechoslovakia. The Sudeten crisis of 1938 was provoked by the Pan-Germanist demands of Germany that the Sudetenland be annexed to Germany, which happened after the later Munich Agreement. Part of the borderland was invaded and annexed by Poland. When Czechoslovakia was reconstituted after the Second World War, the Sudeten Germans were expelled and the region today is inhabited almost exclusively by Czech speakers.

The word Sudetenland is a German compound of Land, meaning "country", and Sudeten, the name of the Sudeten Mountains, which run along the northern Czech border and Lower Silesia (now in Poland). The Sudetenland encompassed areas well beyond those mountains, however.

Parts of the now Czech regions of Karlovy Vary, Liberec, Olomouc, Moravia-Silesia, and Ústí nad Labem are within the area called Sudetenland.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Early origins

1.2 Emergence of the term

1.3 World War I and its aftermath

1.4 Within the Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

1.5 Sudeten Crisis

1.6 Sudetenland as part of Germany

1.7 Expulsions and resettlement after World War II

2 See also

3 References

History

The areas later known as the Sudetenland never formed a single historical region, which makes it difficult to distinguish the history of the Sudetenland apart from that of Bohemia, until the advent of nationalism in the 19th century.

Early origins

The Celtic and Boii tribes settled there and the region was first mentioned on the map of Ptolemaios in the 2nd century AD. The Germanic tribe of the Marcomanni dominated the entire core of the region in later centuries. Those tribes already built cities like Brno, but moved west during the Migration Period. In the 7th century AD Slavic people moved in and were united under Samo's realm. Later in the High Middle Ages Germans settled into the less populated border region.

In the Middle Ages the regions situated on the mountainous border of the Duchy and the Kingdom of Bohemia had since the Migration Period been settled mainly by western Slavic Czechs. Along the Bohemian Forest in the west, the Czech lands bordered on the German Slavic tribes (German Sorbs) stem duchies of Bavaria and Franconia; marches of the medieval German kingdom had also been established in the adjacent Austrian lands south of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands and the northern Meissen region beyond the Ore Mountains. In the course of the Ostsiedlung (settlement of the east) German settlement from the 13th century onwards continued to move into the Upper Lusatia region and the duchies of Silesia north of the Sudetes mountain range.

From as early as the second half of the 13th century onwards these Bohemian border regions were settled by ethnic Germans, who were invited by the Přemyslid Bohemian kings — especially by Ottokar II (1253–1278) and Wenceslaus II (1278–1305). After the extinction of the Přemyslid dynasty in 1306, the Bohemian nobility backed John of Luxembourg as king against his rival Duke Henry of Carinthia. In 1322 King John of Bohemia acquired (for the third time) the formerly Imperial Egerland region in the west and was able to vassalize most of the Piast Silesian duchies, acknowledged by King Casimir III of Poland by the 1335 Treaty of Trentschin. His son, Bohemian King Charles IV, was elected King of the Romans in 1346 and crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 1355. He added the Lusatias to the Lands of the Bohemian Crown, which then comprised large territories with a significant German population.

In the hilly border regions German settlers established major manufactures of forest glass. The situation of the German population was aggravated by the Hussite Wars (1419–1434), though there were also some Germans among the Hussite insurgents.

By then Germans largely settled the hilly Bohemian border regions as well as the cities of the lowlands; mainly people of Bavarian descent in the South Bohemian and South Moravian Region, in Brno, Jihlava, České Budějovice and the West Bohemian Plzeň Region; Franconian people in Žatec; Upper Saxons in adjacent North Bohemia, where the border with the Saxon Electorate was fixed by the 1459 Peace of Eger; Germanic Silesians in the adjacent Sudetes region with the County of Kladsko, in the Moravian–Silesian Region, in Svitavy and Olomouc. The city of Prague had a German-speaking majority from the last third of the 17th century until 1860, but after 1910 the proportion of German speakers had decreased to 6.7% of the population.

From the Luxembourgs, the rule over Bohemia passed through George of Podiebrad to the Jagiellon dynasty and finally to the House of Habsburg in 1526. Both Czech and German Bohemians suffered heavily in the Thirty Years War. Bohemia lost 70% of its population. From the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt that collapsed at the 1620 Battle of White Mountain, the Habsburgs gradually integrated the Kingdom of Bohemia into their monarchy. During the subsequent Counter-Reformation, less populated areas were resettled with Catholic Germans from the Austrian lands. From 1627 the Habsburgs enforced the so-called Verneuerte Landesordnung ("Renewed Land's Constitution") and one of its consequences was that German according to mother tongue gradually became the primary and official language while Czech declined to a secondary role in the Empire. Also in 1749 Austrian Empire enforced German as the official language again. Emperor Joseph II in 1780 renounced the coronation ceremony as Bohemian king and unsuccessfully tried to push German through as sole official language in all Habsburg lands (including Hungary). Nevertheless, German cultural influence grew stronger during the Age of Enlightenment and Weimar Classicism.

On the other hand, in the course of the Romanticism movement national tensions arose, both in the form of the Austroslavism ideology developed by Czech politicians like František Palacký and Pan-Germanist activist raising the German question. Conflicts between Czech and German nationalists emerged in the 19th century, for instance in the Revolutions of 1848: while the German-speaking population of Bohemia and Moravia wanted to participate in the building of a German nation state, the Czech-speaking population insisted on keeping Bohemia out of such plans. The Bohemian Kingdom remained a part of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary until its dismemberment after the First World War.

Emergence of the term

Ethnic distribution in Austria-Hungary in 1911: regions with a German majority are depicted in pink, those with Czech majorities in blue.

In the wake of growing nationalism, the name "Sudetendeutsche" (Sudeten Germans) emerged by the early 20th century. It originally constituted part of a larger classification of three groupings of Germans within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which also included "Alpine Deutschen" (English: Alpine Germans) in what later became the Republic of Austria and "Balkandeutsche" (English: Balkan Germans) in Hungary and the regions east of it. Of these three terms, only the term "Sudetendeutsche" survived, because of the ethnic and cultural conflicts within Bohemia.

World War I and its aftermath

During World War I, what would later be known as the Sudetenland experienced a rate of war deaths higher than most other German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary and exceeded only by German South Moravia and Carinthia. Thirty-four of each 1,000 inhabitants were killed.[1]

Austria-Hungary broke apart at the end of World War I. Late in October 1918, an independent Czechoslovak state, consisting of the lands of the Bohemian kingdom and areas belonging to the Kingdom of Hungary, was proclaimed. The German deputies of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia in the Imperial Council (Reichsrat) referred to the Fourteen Points of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and the right proposed therein to self-determination, and attempted to negotiate the union of the German-speaking territories with the new Republic of German Austria, which itself aimed at joining Weimar Germany.

The German-speaking parts of the former Lands of the Bohemian Crown remained in a newly created Czechoslovakia, a multi-ethnic state of several nations: Czechs, Germans, Slovaks, Hungarians, Poles and Ruthenians. On 20 September 1918, the Prague government asked the United States's opinion for the Sudetenland. President Woodrow Wilson sent Ambassador Archibald Coolidge into Czechoslovakia. After Coolidge became witness of German Bohemian demonstrations,[2] Coolidge suggested the possibility of ceding certain German-speaking parts of Bohemia to Germany (Cheb) and Austria (South Moravia and South Bohemia).[citation needed] He also insisted that the German-inhabited regions of West and North Bohemia remain within Czechoslovakia. The American delegation at the Paris talks, with Allen Dulles as the American's chief diplomat in the Czechoslovak Commission who emphasized preserving the unity of the Czech lands, decided not to follow Coolidge's proposal.[3]

Four regional governmental units were established:

Province of German Bohemia (Provinz Deutschböhmen), the regions of northern and western Bohemia; proclaimed a constitutive state (Land) of the German-Austrian Republic with Reichenberg (Liberec) as capital, administered by a Landeshauptmann (state captain), consecutively: Rafael Pacher (1857–1936), 29 October – 6 November 1918, and Rudolf Ritter von Lodgman von Auen (1877–1962), 6 November – 16 December 1918 (the last principal city was conquered by the Czech army but he continued in exile, first at Zittau in Saxony and then in Vienna, until 24 September 1919).

Province of the Sudetenland (Provinz Sudetenland), the regions of northern Moravia and Austrian Silesia; proclaimed a constituent state of the German-Austrian Republic with Troppau (Opava) as capital, governed by a Landeshauptmann: Robert Freissler (1877–1950), 30 October – 18 December 1918. This province's boundaries do not correspond to what would later be called the Sudetenland, which contained all the German-speaking parts of the Czech lands.

Bohemian Forest Region (Böhmerwaldgau), the region of Bohemian Forest/South Bohemia; proclaimed a district (Kreis) of the existing Austrian Land of Upper Austria; administered by Kreishauptmann (district captain): Friedrich Wichtl (1872–1922) from 30 October 1918.

German South Moravia (Deutschsüdmähren), proclaimed a District (Kreis) of the existing Austrian land Lower Austria, administered by a Kreishauptmann: Oskar Teufel (1880–1946) from 30 October 1918.

The U.S. commission to the Paris Peace Conference issued a declaration which gave unanimous support for "unity of Czech lands".[4] In particular the declaration stated:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The Commission was...unanimous in its recommendation that the separation of all areas inhabited by the German-Bohemians would not only expose Czechoslovakia to great dangers but equally create great difficulties for the Germans themselves. The only practicable solution was to incorporate these Germans into Czechoslovakia.

Several German minorities according to their mother tongue in Moravia—including German-speaking populations in Brno, Jihlava, and Olomouc—also attempted to proclaim their union with German Austria, but failed. The Czechs thus rejected the aspirations of the German Bohemians and demanded the inclusion of the lands inhabited by ethnic Germans in their state, despite the presence of more than 90% (as of 1921) ethnic Germans (which led to the presence of 23.4% of Germans in all of Czechoslovakia), on the grounds they had always been part of lands of the Bohemian Crown. The Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919 affirmed the inclusion of the German-speaking territories within Czechoslovakia. Over the next two decades, some Germans in the Sudetenland continued to strive for a separation of the German-inhabited regions from Czechoslovakia.

Within the Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

Flag flown by Sudeten Germans[5]

Konrad Henlein speaking in Carlsbad, 1937

According to the February 1921 census, 3,123,000 native German speakers lived in Czechoslovakia—23.4% of the total population. The controversies between the Czechs and the German-speaking minority lingered on throughout the 1920s, and intensified in the 1930s.

During the Great Depression the mostly mountainous regions populated by the German minority, together with other peripheral regions of Czechoslovakia, were hurt by the economic depression more than the interior of the country. Unlike the less developed regions (Ruthenia, Moravian Wallachia), the Sudetenland had a high concentration of vulnerable export-dependent industries (such as glass works, textile industry, paper-making, and toy-making industry). Sixty percent of the bijouterie and glass-making industry were located in the Sudetenland, 69% of employees in this sector were Germans speaking according to mother tongue, and 95% of bijouterie and 78% of other glassware was produced for export. The glass-making sector was affected by decreased spending power and also by protective measures in other countries and many German workers lost their work.[6]

The high unemployment, as well as the imposition of Czech in schools and all public spaces, made people more open to populist and extremist movements such as fascism, communism, and German irredentism. In these years, the parties of German nationalists and later the Sudeten German National Socialist Party (SdP) with its radical demands gained immense popularity among Germans in Czechoslovakia.

Sudeten Crisis

Czech inscriptions smeared by Sudeten German activists, March 1938, Teplice (German: Teplitz)

A Sudeten German Voluntary Force ("Sudetendeutsches Freikorps") unit in 1938

The increasing aggressiveness of Hitler prompted the Czechoslovak military to build extensive border fortifications starting in 1936 to defend the troubled border region. Immediately after the Anschluß of Austria into the Third Reich in March 1938, Hitler made himself the advocate of ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, triggering the "Sudeten Crisis". The following month, Sudeten Nazis, led by Konrad Henlein, agitated for autonomy. On 24 April 1938 the SdP proclaimed the Karlsbader Programm, which demanded in eight points the complete equality between the Sudeten Germans and the Czech people. The government accepted these claims on 30 June 1938.[clarification needed][7]

In August, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain sent Lord Runciman on a Mission to Czechoslovakia in order to see if he could obtain a settlement between the Czechoslovak government and the Germans in the Sudetenland. Lord Runciman's first day included meetings with President Beneš and Prime Minister Milan Hodža as well as a direct meeting with the Sudeten Germans from Henlein's SdP. On the next day he met with Dr and Mme Beneš and later met non-Nazi Germans in his hotel.[8]

A full account of his report—including summaries of the conclusions of his meetings with the various parties—which he made in person to the Cabinet on his return to Britain is found in the Document CC 39(38).[9] Lord Runciman[10] expressed sadness that he could not bring about agreement with the various parties, but he agreed with Lord Halifax that the time gained was important. He reported on the situation of the Sudeten Germans, and he gave details of four plans which had been proposed to deal with the crisis, each of which had points which, he reported, made it unacceptable to the other parties to the negotiations.

The four were: Transfer of the Sudetenland to the Reich; hold a plebiscite on the transfer of the Sudetenland to the Reich, organize a Four Power Conference on the matter, create a federal Czechoslovakia. At the meeting, he said that he was very reluctant to offer his own solution; he had not seen this as his task. The most that he said was that the great centres of opposition were in Eger and Asch, in the northwestern corner of Bohemia, which contained about 800,000 Germans and very few others.

He did say that the transfer of these areas to Germany would almost certainly be a good thing; he added that the Czechoslovak army would certainly oppose this very strongly, and that Beneš had said that they would fight rather than accept it.[11]

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain met Adolf Hitler in Berchtesgaden on 15 September and agreed to the cession of the Sudetenland; three days later, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier did the same. No Czechoslovak representative was invited to these discussions. Germany was now able to walk into the Sudetenland without firing a shot.

Chamberlain met Hitler in Godesberg on 22 September to confirm the agreements. Hitler, aiming to use the crisis as a pretext for war, now demanded not only the annexation of the Sudetenland but the immediate military occupation of the territories, giving the Czechoslovak army no time to adapt their defence measures to the new borders.

Hitler in a speech at the Sportpalast in Berlin claimed that the Sudetenland was "the last territorial demand I have to make in Europe"[12] and gave Czechoslovakia a deadline of 28 September at 2:00pm to cede the Sudetenland to Germany or face war.[13]

To achieve a solution, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini suggested a conference of the major powers in Munich and on 29 September, Hitler, Daladier and Chamberlain met and agreed to Mussolini's proposal (actually prepared by Hermann Göring) and signed the Munich Agreement, accepting the immediate occupation of the Sudetenland. The Czechoslovak government, though not party to the talks, submitted to compulsion and promised to abide by the agreement on 30 September.

The Sudetenland was assigned to Germany between 1 October and 10 October 1938. The Czech part of Czechoslovakia was subsequently invaded by Germany in March 1939, with a portion being annexed and the remainder turned into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The Slovak part declared its independence from Czechoslovakia, becoming the Slovak Republic (Slovak State), a satellite state and ally of Germany. (The Ruthenian part – Subcarpathian Rus – made also an attempt to declare its sovereignty as Carpatho-Ukraine but only with ephemeral success. This area was annexed by Hungary.)

Part of the borderland was also invaded and annexed by Poland.

The Catholic Requiem of fallen Czech policemen and security officials killed in a skirmish by Sudeten German Freecorps members, at Falkenau an der Eger (Czech: Sokolov) in the Egerland

Ethnic Germans in the city of Eger (Czech: Cheb) greeting Hitler with the Nazi salute after he crossed the border into the formerly Czechoslovak Sudetenland on 3 October 1938

Volunteers of the Sudeten German Free Corps (German: Sudetendeutsches Freikorps) receiving refreshments from the local population in the city of Eger (Czech: Cheb)

Adolf Hitler drives through the crowd in Eger, 3 October 1938

Sudetenland as part of Germany

Combining Sudeten German Party and NSDAP, October 1938

The Sudetenland was initially put under military administration, with General Wilhelm Keitel as military governor. On 21 October 1938, the annexed territories were divided, with the southern parts being incorporated into the neighbouring Reichsgaue Niederdonau, Oberdonau and Bayerische Ostmark.

Election ballot, Reichsgau Sudetenland, December 1938

The northern and western parts were reorganized as the Reichsgau Sudetenland, with the city of Reichenberg (present-day Liberec) established as its capital. Konrad Henlein (now openly a NSDAP member) administered the district first as Reichskommissar (until 1 May 1939) and then as Reichsstatthalter (1 May 1939 – 4 May 1945). The Sudetenland consisted of three administrative districts (Regierungsbezirke): Eger (with Karlsbad as capital), Aussig (Aussig) and Troppau (Troppau).

Sudetenland was administered by Konrad Henlein for the duration of the war

Shortly after the annexation, the Jews living in the Sudetenland were persecuted widely. Only a few weeks afterwards, the Kristallnacht occurred. As elsewhere in Germany, many synagogues were set on fire and numerous leading Jews were sent to concentration camps. In later years, the Nazis transported up to 300,000 Czech and Slovak Jews to concentration camps,[14] where many of them died or were killed. Jews and Czechs were not the only afflicted peoples; German socialists, communists and pacifists were widely persecuted as well. Some of the German socialists fled the Sudetenland via Prague and London to other countries. The Gleichschaltung would permanently alter the community in the Sudetenland.

Despite this, on 4 December 1938 there were elections in Reichsgau Sudetenland, in which 97.32% of the adult population voted for NSDAP. About a half million Sudeten Germans joined the Nazi Party which was 17.34% of the total German population in the Sudetenland (the average NSDAP membership participation in Germany was merely 7.85% in 1944). This means the Sudetenland was one of the most pro-Nazi regions of the Third Reich.[15] Because of their knowledge of the Czech language, many Sudeten Germans were employed in the administration of the ethnic Czech Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as well as in Nazi organizations (Gestapo, etc.). The most notable was Karl Hermann Frank: the SS and Police general and Secretary of State in the Protectorate.

Administrative Divisions of Reichsgau Sudetenland

Expulsions and resettlement after World War II

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia as the result of the end of World War II

From the territory occupied by the Third Reich, 160,000 to 170,000 Czech-speaking inhabitants were forced to leave or were expelled

Shortly after the liberation of Czechoslovakia in May 1945, the use of the term Sudety (Sudetenland) in official communications was banned and replaced by the term pohraniční území (border territory).[16]

After World War II in summer 1945 the Potsdam Conference decided that Sudeten Germans would have to leave Czechoslovakia (see Expulsion of Germans after World War II). As a consequence of the immense hostility against all Germans that had grown within Czechoslovakia due to Nazi behavior, the overwhelming majority of Germans were expelled (while the relevant Czechoslovak legislation provided for the remaining Germans who were able to prove their anti-Nazi affiliation).

The number of expelled Germans in the early phase (spring–summer 1945) is estimated to be around 500,000 people. Following the Beneš decrees and starting in 1946, the majority of the Germans were expelled and in 1950 only 159,938 (from 3,149,820 in 1930) still lived in the Czech Republic. The remaining Germans, proven anti-fascists and skilled laborers, were allowed to stay in Czechoslovakia, but were later forcefully dispersed within the country.[17] Some German refugees from Czechoslovakia are represented by the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft.

Many of the Germans who stayed in Czechoslovakia later emigrated to West Germany (more than 100,000). As the German population was transferred out of the country, the former Sudetenland was resettled, mostly by Czechs but also by other nationalities of Czechoslovakia: Slovaks, Greeks (arriving in the wake of the Greek Civil War 1946–49), Carpathian Ruthenians, Romani people and Jews who had survived the Holocaust, and Hungarians (though the Hungarians were forced into this and later returned home—see Hungarians in Slovakia: Population exchanges).

Some areas—such as part of Czech Silesian-Moravian borderland, southwestern Bohemia (Šumava National Park), western and northern parts of Bohemia—remained depopulated for several strategic reasons (extensive mining and military interests) or are now protected national parks and landscapes. Moreover, before the establishment of the Iron Curtain in 1952–55, the so-called "forbidden zone" was established (by means of engineer equipment) up to 2 km (1.2 mi) from the border in which no civilians could reside. A wider region, or "border zone" existed, up to 12 km from the border, in which no "disloyal" or "suspect" civilians could reside or work. Thus, the entire Aš-Bulge fell within the border zone; this status remained until the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

There remained areas with noticeable German minorities in the westernmost borderland around Cheb, where skilled ethnic German miners and workers continued in mining and industry until 1955, sanctioned under the Yalta Conference protocols[citation needed]; in the Egerland, German minority organizations continue to exist. Also, the small town of Kravaře (German: Deutsch Krawarn) in the multiethnic Hlučín Region of Czech Silesia has an ethnic German majority (2006), including an ethnic German mayor.

In the 2001 census, approximately 40,000 people in the Czech Republic claimed German ethnicity.

See also

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Beneš decrees

- Bohemian Forest Region

- Expulsion of Germans after World War II

Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia- German Austria

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia

- German South Moravia

- Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators in Czechoslovakia

- Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft

- Sudetenland Medal

References

- Notes

^ Rothenburg, G. The Army of Francis Joseph. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1976. p 218.

^ "em. o. Prof. Dr. Gerard Radnitzky, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy of Science at the University of Trier, Germany, Vertreibung vor dem Krieg geplant — Ethnic cleansing was planned before the war, 3. May 2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2013-05-01..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Bruegel, Johann Wolfgang (1973). Czechoslovakia Before Munich. Cambridge University Press. p. 44.

^ Bruegel, Johann Wolfgang (1973). Czechoslovakia Before Munich. Cambridge University Press. p. 45.

^ "Sudetenland (flag)". Flaggenlexikon.de. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

^ Kárník, Zdeněk. České země v éře první republiky (1918–1938). Díl 2. Praha 2002.

^ Zayas, Alfred Maurice de: Die Nemesis von Potsdam. Die Anglo-Amerikaner und die Vertreibung der Deutschen, überarb. u. erweit. Neuauflage, Herbig-Verlag, München, 2005.

^ iPad iPhone Android TIME TV Populist The Page (1938-08-15). "CZECHOSLOVAKIA: Pax Runciman". TIME. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

^ "The Cabinet Papers | CAB 23 interwar conclusions". Nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

^ Note, what he reports is an expression of his opinion on the situation. He may have been entirely mistaken on this, but it helps us to understand how he saw the situation. For example, that he felt that the Czechoslovakian government being blind to the situation, does not make it true.

^ cab-23-95.pdf p71; CC 39(38) p 4.

^ Max Domarus; Adolf Hitler (1990). Hitler: speeches and proclamations, 1932-1945 : the chronicle of a dictatorship. p. 1393.

^ Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings. New York, New York, USA: Enigma Books, 2008.

ISBN 9781929631421. Pp. 73.

^ Wheeler, Charles (2002-12-03). "Czechs' hidden revenge against Germans". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

^ Zimmermann, Volker: Die Sudetendeutschen im NS-Staat. Politik und Stimmung der Bevölkerung im Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945). Essen 1999. (

ISBN 3-88474-770-3)

^ Zdeněk Beneš. Facing history: the evolution of Czech-German relations in the Czech provinces, 1848–1948. Gallery, 2002. p. 218.

^ "Přesun v rámci rozptylu občanů německé národnosti."

Timeline of Czechoslovak statehood | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pre-1918 | 1918–1938 | 1938–1945 | 1945–1948 | 1948–1989 | 1989–1992 | 1993– | ||||

Bohemia Moravia Silesia | Austrian Empire | First Republica | Sudetenlandb | Third Republic | Czechoslovak Republice 1948–1960 | Czechoslovak Socialist Republicf 1960–1990 | Czech and Slovak Federative Republic 1990–1992 | Czech Republic | ||

Second Republicc 1938–1939 | Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–1945 | |||||||||

Slovakia | Kingdom of Hungary | Slovak Republic 1939–1945 | Slovakia | |||||||

Southern Slovakia and Carpatho-Ukrained | ||||||||||

Carpathian Ruthenia | Zakarpattia Oblastg 1944 / 1946 – 1991 | Zakarpattia Oblasth 1991–present | ||||||||

Austria-Hungary | Czechoslovak government-in-exile | |||||||||

a ČSR; boundaries and government established by the 1920 constitution. | e ČSR; declared a "people's democracy" (without a formal name change) under the Ninth-of-May Constitution following the 1948 coup. | |||||||||