Topology

Möbius strips, which have only one surface and one edge, are a kind of object studied in topology.

In mathematics, topology (from the Greek τόπος, place, and λόγος, study) is concerned with the properties of space that are preserved under continuous deformations, such as stretching, twisting, crumpling and bending, but not tearing or gluing.

An n-dimensional topological space is a space (not necessarily Euclidean) with certain properties of connectedness and compactness.[1]

The space may be continuous (like all points on a rubber sheet), or discrete (like the set of integers). It can be open (like the set of points inside a circle) or closed (like the set of points inside a circle, together with the points on the circle).

Topology developed as a field of study out of geometry and set theory, through analysis of concepts such as space, dimension, and transformation.[2] Such ideas go back to Gottfried Leibniz, who in the 17th century envisioned the geometria situs (Greek-Latin for "geometry of place") and analysis situs (Greek-Latin for "picking apart of place"). Leonhard Euler's Seven Bridges of Königsberg Problem and Polyhedron Formula are arguably the field's first theorems. The term topology was introduced by Johann Benedict Listing in the 19th century, although it was not until the first decades of the 20th century that the idea of a topological space was developed. By the middle of the 20th century, topology had become a major branch of mathematics.

A three-dimensional depiction of a thickened trefoil knot, the simplest non-trivial knot

Contents

1 History

2 Introduction

3 Concepts

3.1 Topologies on sets

3.2 Continuous functions and homeomorphisms

3.3 Manifolds

4 Topics

4.1 General topology

4.2 Algebraic topology

4.3 Differential topology

4.4 Geometric topology

4.5 Generalizations

5 Applications

5.1 Biology

5.2 Computer science

5.3 Physics

5.4 Geography and Landscape Ecology

5.5 Robotics

5.6 Games and puzzles

5.7 Fiber Art

6 See also

7 References

7.1 Citations

7.2 Bibliography

8 Further reading

9 External links

History

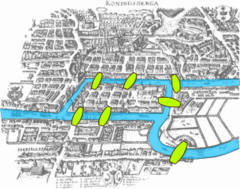

The Seven Bridges of Königsberg was a problem solved by Euler.

Topology, as a well-defined mathematical discipline, originates in the early part of the twentieth century, but some isolated results can be traced back several centuries.[3] Among these are certain questions in geometry investigated by Leonhard Euler. His 1736 paper on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg is regarded as one of the first practical applications of topology.[3] On 14 November 1750, Euler wrote to a friend that he had realised the importance of the edges of a polyhedron. This led to his polyhedron formula, V − E + F = 2 (where V, E and F respectively indicate the number of vertices, edges and faces of the polyhedron). Some authorities regard this analysis as the first theorem, signalling the birth of topology.[4][5]

Further contributions were made by Augustin-Louis Cauchy, Ludwig Schläfli, Johann Benedict Listing, Bernhard Riemann and Enrico Betti.[6] Listing introduced the term "Topologie" in Vorstudien zur Topologie, written in his native German, in 1847, having used the word for ten years in correspondence before its first appearance in print.[7] The English form "topology" was used in 1883 in Listing's obituary in the journal Nature to distinguish "qualitative geometry from the ordinary geometry in which quantitative relations chiefly are treated".[8] The term "topologist" in the sense of a specialist in topology was used in 1905 in the magazine Spectator.[citation needed]

Their work was corrected, consolidated and greatly extended by Henri Poincaré. In 1895, he published his ground-breaking paper on Analysis Situs, which introduced the concepts now known as homotopy and homology, which are now considered part of algebraic topology.[6]

| Manifold | Euler num | Orientability | Betti numbers | Torsion coefficient(1-dim) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b0 | b1 | b2 | ||||

| Sphere | 2 | Orientable | 1 | 0 | 1 | none |

| Torus | 0 | Orientable | 1 | 2 | 1 | none |

| 2-holed torus | −2 | Orientable | 1 | 4 | 1 | none |

g-holed torus (Genus = g) | 2 − 2g | Orientable | 1 | 2g | 1 | none |

| Projective plane | 1 | Non-orientable | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Klein bottle | 0 | Non-orientable | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Sphere with c cross-caps (c > 0) | 2 − c | Non-orientable | 1 | c − 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 2-Manifold with g holes and c cross-caps (c > 0) | 2 − (2g + c) | Non-orientable | 1 | (2g + c) − 1 | 0 | 2 |

Unifying the work on function spaces of Georg Cantor, Vito Volterra, Cesare Arzelà, Jacques Hadamard, Giulio Ascoli and others, Maurice Fréchet introduced the metric space in 1906.[9] A metric space is now considered a special case of a general topological space, with any given topological space potentially giving rise to many distinct metric spaces. In 1914, Felix Hausdorff coined the term "topological space" and gave the definition for what is now called a Hausdorff space.[10] Currently, a topological space is a slight generalization of Hausdorff spaces, given in 1922 by Kazimierz Kuratowski.[11]

Modern topology depends strongly on the ideas of set theory, developed by Georg Cantor in the later part of the 19th century. In addition to establishing the basic ideas of set theory, Cantor considered point sets in Euclidean space as part of his study of Fourier series. For further developments, see point-set topology and algebraic topology.

Introduction

Topology can be formally defined as "the study of qualitative properties of certain objects (called topological spaces) that are invariant under a certain kind of transformation (called a continuous map), especially those properties that are invariant under a certain kind of invertible transformation (called homeomorphisms)."

Topology is also used to refer to a structure imposed upon a set X, a structure that essentially 'characterizes' the set X as a topological space by taking proper care of properties such as convergence, connectedness and continuity, upon transformation.

Topological spaces show up naturally in almost every branch of mathematics. This has made topology one of the great unifying ideas of mathematics.

The motivating insight behind topology is that some geometric problems depend not on the exact shape of the objects involved, but rather on the way they are put together. For example, the square and the circle have many properties in common: they are both one dimensional objects (from a topological point of view) and both separate the plane into two parts, the part inside and the part outside.

In one of the first papers in topology, Leonhard Euler demonstrated that it was impossible to find a route through the town of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) that would cross each of its seven bridges exactly once. This result did not depend on the lengths of the bridges, nor on their distance from one another, but only on connectivity properties: which bridges connect to which islands or riverbanks. This problem in introductory mathematics called Seven Bridges of Königsberg led to the branch of mathematics known as graph theory.

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Similarly, the hairy ball theorem of algebraic topology says that "one cannot comb the hair flat on a hairy ball without creating a cowlick." This fact is immediately convincing to most people, even though they might not recognize the more formal statement of the theorem, that there is no nonvanishing continuous tangent vector field on the sphere. As with the Bridges of Königsberg, the result does not depend on the shape of the sphere; it applies to any kind of smooth blob, as long as it has no holes.

To deal with these problems that do not rely on the exact shape of the objects, one must be clear about just what properties these problems do rely on. From this need arises the notion of homeomorphism. The impossibility of crossing each bridge just once applies to any arrangement of bridges homeomorphic to those in Königsberg, and the hairy ball theorem applies to any space homeomorphic to a sphere.

Intuitively, two spaces are homeomorphic if one can be deformed into the other without cutting or gluing. A traditional joke is that a topologist cannot distinguish a coffee mug from a doughnut, since a sufficiently pliable doughnut could be reshaped to a coffee cup by creating a dimple and progressively enlarging it, while shrinking the hole into a handle.[12]

Homeomorphism can be considered the most basic topological equivalence. Another is homotopy equivalence. This is harder to describe without getting technical, but the essential notion is that two objects are homotopy equivalent if they both result from "squishing" some larger object.

| Homeomorphism | Homotopy equivalence |

|---|---|

|

An introductory exercise is to classify the uppercase letters of the English alphabet according to homeomorphism and homotopy equivalence. The result depends partially on the font used. The figures use the sans-serif Myriad font. Homotopy equivalence is a rougher relationship than homeomorphism; a homotopy equivalence class can contain several homeomorphism classes. The simple case of homotopy equivalence described above can be used here to show two letters are homotopy equivalent. For example, O fits inside P and the tail of the P can be squished to the "hole" part.

Homeomorphism classes are:

- no holes corresponding with C, G, I, J, L, M, N, S, U, V, W, and Z;

- no holes and three tails corresponding with E, F, T, and Y[clarification needed];

- no holes and four tails corresponding with X;

- one hole and no tail corresponding with D and O;

- one hole and one tail corresponding with P and Q;

- one hole and two tails corresponding with A and R;

- two holes and no tail corresponding with B; and

- a bar with four tails corresponding with H and K; the "bar" on the K is almost too short to see.

Homotopy classes are larger, because the tails can be squished down to a point. They are:

- one hole,

- two holes, and

- no holes.

To classify the letters correctly, we must show that two letters in the same class are equivalent and two letters in different classes are not equivalent. In the case of homeomorphism, this can be done by selecting points and showing their removal disconnects the letters differently. For example, X and Y are not homeomorphic because removing the center point of the X leaves four pieces; whatever point in Y corresponds to this point, its removal can leave at most three pieces. The case of homotopy equivalence is harder and requires a more elaborate argument showing an algebraic invariant, such as the fundamental group, is different on the supposedly differing classes.

Letter topology has practical relevance in stencil typography. For instance, Braggadocio font stencils are made of one connected piece of material.

Concepts

Topologies on sets

The term topology also refers to a specific mathematical idea central to the area of mathematics called topology. Informally, a topology tells how elements of a set relate spatially to each other. The same set can have different topologies. For instance, the real line, the complex plane (which is a 1-dimensional complex vector space), and the Cantor set can be thought of as the same set with different topologies.

Formally, let X be a set and let τ be a family of subsets of X. Then τ is called a topology on X if:

- Both the empty set and X are elements of τ.

- Any union of elements of τ is an element of τ.

- Any intersection of finitely many elements of τ is an element of τ.

If τ is a topology on X, then the pair (X, τ) is called a topological space. The notation Xτ may be used to denote a set X endowed with the particular topology τ.

The members of τ are called open sets in X. A subset of X is said to be closed if its complement is in τ (i.e., its complement is open). A subset of X may be open, closed, both (clopen set), or neither. The empty set and X itself are always both closed and open. A subset of X including an open set containing a point x is called a 'neighborhood' of x.

Continuous functions and homeomorphisms

A function or map from one topological space to another is called continuous if the inverse image of any open set is open. If the function maps the real numbers to the real numbers (both spaces with the standard topology), then this definition of continuous is equivalent to the definition of continuous in calculus. If a continuous function is one-to-one and onto, and if the inverse of the function is also continuous, then the function is called a homeomorphism and the domain of the function is said to be homeomorphic to the range. Another way of saying this is that the function has a natural extension to the topology. If two spaces are homeomorphic, they have identical topological properties, and are considered topologically the same. The cube and the sphere are homeomorphic, as are the coffee cup and the doughnut. But the circle is not homeomorphic to the doughnut.

Manifolds

While topological spaces can be extremely varied and exotic, many areas of topology focus on the more familiar class of spaces known as manifolds. A manifold is a topological space that resembles Euclidean space near each point. More precisely, each point of an n-dimensional manifold has a neighbourhood that is homeomorphic to the Euclidean space of dimension n. Lines and circles, but not figure eights, are one-dimensional manifolds. Two-dimensional manifolds are also called surfaces. Examples include the plane, the sphere, and the torus, which can all be realized without self-intersection in three dimensions, but also the Klein bottle and real projective plane, which cannot.

Topics

General topology

General topology is the branch of topology dealing with the basic set-theoretic definitions and constructions used in topology.[13][14] It is the foundation of most other branches of topology, including differential topology, geometric topology, and algebraic topology. Another name for general topology is point-set topology.

The fundamental concepts in point-set topology are continuity, compactness, and connectedness. Intuitively, continuous functions take nearby points to nearby points. Compact sets are those that can be covered by finitely many sets of arbitrarily small size. Connected sets are sets that cannot be divided into two pieces that are far apart. The words nearby, arbitrarily small, and far apart can all be made precise by using open sets. If we change the definition of open set, we change what continuous functions, compact sets, and connected sets are. Each choice of definition for open set is called a topology. A set with a topology is called a topological space.

Metric spaces are an important class of topological spaces where distances can be assigned a number called a metric. Having a metric simplifies many proofs, and many of the most common topological spaces are metric spaces.

Algebraic topology

Algebraic topology is a branch of mathematics that uses tools from abstract algebra to study topological spaces.[15] The basic goal is to find algebraic invariants that classify topological spaces up to homeomorphism, though usually most classify up to homotopy equivalence.

The most important of these invariants are homotopy groups, homology, and cohomology.

Although algebraic topology primarily uses algebra to study topological problems, using topology to solve algebraic problems is sometimes also possible. Algebraic topology, for example, allows for a convenient proof that any subgroup of a free group is again a free group.

Differential topology

Differential topology is the field dealing with differentiable functions on differentiable manifolds.[16] It is closely related to differential geometry and together they make up the geometric theory of differentiable manifolds.

More specifically, differential topology considers the properties and structures that require only a smooth structure on a manifold to be defined. Smooth manifolds are 'softer' than manifolds with extra geometric structures, which can act as obstructions to certain types of equivalences and deformations that exist in differential topology. For instance, volume and Riemannian curvature are invariants that can distinguish different geometric structures on the same smooth manifold—that is, one can smoothly "flatten out" certain manifolds, but it might require distorting the space and affecting the curvature or volume.

Geometric topology

Geometric topology is a branch of topology that primarily focuses on low-dimensional manifolds (i.e. spaces of dimensions 2,3 and 4) and their interaction with geometry, but it also includes some higher-dimensional topology.[17][18] Some examples of topics in geometric topology are orientability, handle decompositions, local flatness, crumpling and the planar and higher-dimensional Schönflies theorem.

In high-dimensional topology, characteristic classes are a basic invariant, and surgery theory is a key theory.

Low-dimensional topology is strongly geometric, as reflected in the uniformization theorem in 2 dimensions – every surface admits a constant curvature metric; geometrically, it has one of 3 possible geometries: positive curvature/spherical, zero curvature/flat, negative curvature/hyperbolic – and the geometrization conjecture (now theorem) in 3 dimensions – every 3-manifold can be cut into pieces, each of which has one of eight possible geometries.

2-dimensional topology can be studied as complex geometry in one variable (Riemann surfaces are complex curves) – by the uniformization theorem every conformal class of metrics is equivalent to a unique complex one, and 4-dimensional topology can be studied from the point of view of complex geometry in two variables (complex surfaces), though not every 4-manifold admits a complex structure.

Generalizations

Occasionally, one needs to use the tools of topology but a "set of points" is not available. In pointless topology one considers instead the lattice of open sets as the basic notion of the theory,[19] while Grothendieck topologies are structures defined on arbitrary categories that allow the definition of sheaves on those categories, and with that the definition of general cohomology theories.[20]

Applications

Biology

Knot theory, a branch of topology, is used in biology to study the effects of certain enzymes on DNA. These enzymes cut, twist, and reconnect the DNA, causing knotting with observable effects such as slower electrophoresis.[21] Topology is also used in evolutionary biology to represent the relationship between phenotype and genotype.[22] Phenotypic forms that appear quite different can be separated by only a few mutations depending on how genetic changes map to phenotypic changes during development. In neuroscience, topological quantities like the Euler characteristic and Betti number have been used to measure the complexity of patterns of activity in neural networks.

Computer science

Topological data analysis uses techniques from algebraic topology to determine the large scale structure of a set (for instance, determining if a cloud of points is spherical or toroidal). The main method used by topological data analysis is:

- Replace a set of data points with a family of simplicial complexes, indexed by a proximity parameter.

- Analyse these topological complexes via algebraic topology – specifically, via the theory of persistent homology.[23]

- Encode the persistent homology of a data set in the form of a parameterized version of a Betti number, which is called a barcode.[23]

Physics

Topology is relevant to physics in areas such as condensed matter physics,[24]quantum field theory and physical cosmology.

The topological dependence of mechanical properties in solids is of interest in disciplines of mechanical engineering and materials science. Electrical and mechanical properties depend on the arrangement and network structures of molecules and elementary units in materials.[25] The compressive strength of crumpled topologies is studied in attempts to understand the high strength to weight of such structures that are mostly empty space.[26] Topology is of further significance in Contact mechanics where the dependence of stiffness and friction on the dimensionality of surface structures is the subject of interest with applications in multi-body physics.

A topological quantum field theory (or topological field theory or TQFT) is a quantum field theory that computes topological invariants.

Although TQFTs were invented by physicists, they are also of mathematical interest, being related to, among other things, knot theory, the theory of four-manifolds in algebraic topology, and to the theory of moduli spaces in algebraic geometry. Donaldson, Jones, Witten, and Kontsevich have all won Fields Medals for work related to topological field theory.

The topological classification of Calabi-Yau manifolds has important implications in string theory, as different manifolds can sustain different kinds of strings.[27]

In cosmology, topology can be used to describe the overall shape of the universe.[28] This area of research is commonly known as spacetime topology.

Geography and Landscape Ecology

Topological methods have been used to evaluate the complexity of geomorphological and ecological functions in a landscape and can be applied on geographic maps, or field observations (Papadimitriou, 2013), or even on models and programs representing such functions and their changes in time (Papadimitriou, 2012).

Robotics

The possible positions of a robot can be described by a manifold called configuration space.[29] In the area of motion planning, one finds paths between two points in configuration space. These paths represent a motion of the robot's joints and other parts into the desired pose.[30]

Games and puzzles

Tanglement puzzles are based on topological aspects of the puzzle's shapes and components.[31][32][33][34]

Fiber Art

In order to create a continuous join of pieces in a modular construction, it is necessary to create an unbroken path in an order which surrounds each piece and traverses each edge only once. This process is an application of the Eulerian path.[35]

See also

- Equivariant topology

- List of algebraic topology topics

- List of examples in general topology

- List of general topology topics

- List of geometric topology topics

- List of topology topics

- Publications in topology

- Topoisomer

- Topology glossary

- Topological geometry

- Topological order

References

Citations

^ "the definition of topology"..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Bruner, Robert (2000). "What is Topology? A short and idiosyncratic answer".

^ ab Croom 1989, p. 7

^ Richeson 2008, p. 63

^ Aleksandrov 1969, p. 204

^ abc Richeson (2008)

^ Listing, Johann Benedict, "Vorstudien zur Topologie", Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, Göttingen, p. 67, 1848

^ Tait, Peter Guthrie, "Johann Benedict Listing (obituary)", Nature 27, 1 February 1883, pp. 316–317

^ Fréchet, Maurice (1906). Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel. PhD dissertation. OCLC 8897542.

^ Hausdorff, Felix, "Grundzüge der Mengenlehre", Leipzig: Veit. In (Hausdorff Werke, II (2002), 91–576)

^ Croom 1989, p. 129

^ Hubbard, John H.; West, Beverly H. (1995). Differential Equations: A Dynamical Systems Approach. Part II: Higher-Dimensional Systems. Texts in Applied Mathematics. 18. Springer. p. 204. ISBN 978-0387943770.

^ Munkres, James R. Topology. Vol. 2. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2000.

^ Adams, Colin Conrad, and Robert David Franzosa. Introduction to topology: pure and applied. Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008.

^ Allen Hatcher, Algebraic topology. (2002) Cambridge University Press, xii+544 pp.

ISBN 052179160X, 0521795400.

^ Lee, John M. (2006). Introduction to Smooth Manifolds. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387954486.

^ Budney, Ryan (2011). "What is geometric topology?". mathoverflow.net. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

^ R.B. Sher and R.J. Daverman (2002), Handbook of Geometric Topology, North-Holland.

ISBN 0444824324

^ Johnstone, Peter T. (1983). "The point of pointless topology". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 8 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-1983-15080-2.

^ Artin, Michael (1962). Grothendieck topologies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, Dept. of Mathematics. Zbl 0208.48701.

^ Adams, Colin (2004). The Knot Book: An Elementary Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Knots. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0821836781

^ Stadler, Bärbel M.R.; Stadler, Peter F.; Wagner, Günter P.; Fontana, Walter (2001). "The Topology of the Possible: Formal Spaces Underlying Patterns of Evolutionary Change". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 213 (2): 241–274. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.63.7808. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2423. PMID 11894994.

^ ab Gunnar Carlsson (April 2009). "Topology and data" (PDF). Bulletin (New Series) of the American Mathematical Society. 46 (2): 255–308. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-09-01249-X.

^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2016". Nobel Foundation. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

^ Stephenson, C.; et., al. (2017). "Topological properties of a self-assembled electrical network via ab initio calculation". Sci. Rep. 7: 41621. Bibcode:2017NatSR...741621S. doi:10.1038/srep41621. PMC 5290745. PMID 28155863.

^ Cambou, Anne Dominique; Narayanan, Menon (2011). "Three-dimensional structure of a sheet crumpled into a ball". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (36): 14741–14745. arXiv:1203.5826. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10814741C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019192108. PMC 3169141. PMID 21873249.

^ Yau, S. & Nadis, S.; The Shape of Inner Space, Basic Books, 2010.

^ The Shape of Space: How to Visualize Surfaces and Three-dimensional Manifolds 2nd ed (Marcel Dekker, 1985,

ISBN 082477437X)

^ John J. Craig, Introduction to Robotics: Mechanics and Control, 3rd Ed. Prentice-Hall, 2004

^ Michael Farber, Invitation to Topological Robotics, European Mathematical Society, 2008

^ https://math.stackexchange.com How to reason about disentanglement puzzles.

^ Horak, Mathew (2006). "Disentangling Topological Puzzles by Using Knot Theory". Mathematics Magazine. 79 (5): 368–375. doi:10.2307/27642974. JSTOR 27642974..

^ http://sma.epfl.ch/Notes.pdf A Topological Puzzle, Inta Bertuccioni, December 2003.

^ https://www.futilitycloset.com/the-figure-8-puzzle The Figure Eight Puzzle, Science and Math, June 2012.

^ Eckman, Edie: Connect the shapes crochet motifs: creative techniques for joining motifs of all shapes. ©2012 Storey Publishing

Bibliography

Aleksandrov, P.S. (1969) [1956], "Chapter XVIII Topology", in Aleksandrov, A.D.; Kolmogorov, A.N.; Lavrent'ev, M.A., Mathematics / Its Content, Methods and Meaning (2nd ed.), The M.I.T. Press

Croom, Fred H. (1989), Principles of Topology, Saunders College Publishing, ISBN 9780030298042

Papadimitriou, Fivos (2012). "Artificial Intelligence in modelling the complexity of Mediterranean landscape transformations". Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 81: 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2011.11.009.

Papadimitriou, Fivos (2013). "Mathematical modelling of land use and landscape complexity with ultrametric topology". Journal of Land Use Science. 8 (2): 234–254. doi:10.1080/1747423X.2011.637136.

Richeson, D. (2008), Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology, Princeton University Press

Further reading

Ryszard Engelking, General Topology, Heldermann Verlag, Sigma Series in Pure Mathematics, December 1989,

ISBN 3885380064.

Bourbaki; Elements of Mathematics: General Topology, Addison–Wesley (1966).

Breitenberger, E. (2006). "Johann Benedict Listing". In James, I.M. History of Topology. North Holland. ISBN 978-0444823755.

Kelley, John L. (1975). General Topology. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387901251.

Brown, Ronald (2006). Topology and Groupoids. Booksurge. ISBN 978-1419627224. (Provides a well motivated, geometric account of general topology, and shows the use of groupoids in discussing van Kampen's theorem, covering spaces, and orbit spaces.)

Wacław Sierpiński, General Topology, Dover Publications, 2000,

ISBN 0486411486

Pickover, Clifford A. (2006). The Möbius Strip: Dr. August Möbius's Marvelous Band in Mathematics, Games, Literature, Art, Technology, and Cosmology. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1560258261. (Provides a popular introduction to topology and geometry)

Gemignani, Michael C. (1990) [1967], Elementary Topology (2nd ed.), Dover Publications Inc., ISBN 978-0486665221

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Topology. |

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Topology |

Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Topology, general", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

Elementary Topology: A First Course Viro, Ivanov, Netsvetaev, Kharlamov.

Topology at Curlie

The Topological Zoo at The Geometry Center.- Topology Atlas

Topology Course Lecture Notes Aisling McCluskey and Brian McMaster, Topology Atlas.- Topology Glossary

Moscow 1935: Topology moving towards America, a historical essay by Hassler Whitney.