Turkmens

Turkmens in folk costume at the 20th Independence Day parade, 27 October 2011 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 5.4 million[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,948,000[1] | |

| 719,000[2] | |

| 200,000[3] | |

| 152,000[4] | |

| 5,000[5] | |

| 46,885[6] | |

| 15,171[7] | |

| 7,709[8] | |

| 5,000 | |

| 80 | |

| Languages | |

| Turkmen | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Salar, Yörük, and other Turkic peoples | |

a. ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; a sum of all the referenced populations. | |

Turkmens (Turkmen: Türkmenler, Түркменлер, IPA: [tʏɾkmɛnˈlɛɾ]; historically also the Turkmen) are a nation and Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily the Turkmen nation state of Turkmenistan. Smaller communities are also found in Iran, Afghanistan, North Caucasus (Stavropol Krai), and northern Pakistan. They speak the Turkmen language, which is classified as a part of the Eastern Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages. Examples of other Oghuz languages are Turkish, Azerbaijani, Qashqai, Gagauz, Khorasani, and Salar.[9]

Contents

1 Origins

2 History

3 Language

4 Ethnogenesis

5 Religion

6 Culture and society

6.1 Nomadic heritage

6.2 Society today

6.3 Turkmen in Iran

6.4 Turkmen in Afghanistan

6.5 Turkmen of Stavropol Region of Russia

7 Demographics and population distribution

8 Y-DNA haplogroups of Turkmens

9 See also

10 References

11 Sources

12 External links

Origins

Originally, all Turkic tribes that were part of the Turkic dynastic mythological system (for example, Uigurs, Karluks, and a number of other tribes) were designated "Turkmens". Only later did this word come to refer to a specific ethnonym. The term derives from Türk plus the Sogdian affix of similarity -myn, -men, and means "resembling a Türk" or "co-Türk".[10] A prominent Turkic scholar, Mahmud Kashgari, also mentions the etymology Türk manand (like Turks). The language and ethnicity of the Turkmen were much influenced by their migration to the west. Kashgari calls the Karluks Turkmen as well, but the first time the etymology Turkmen was used was by Makdisi in the second half of the 10th century AD. Like Kashgari, he wrote that the Karluks and Oghuz Turks were called Turkmen. Some modern scholars have proposed that the element -man/-men acts as an intensifier, and have translated the word as "pure Turk" or "most Turk-like of the Turks".[11] Among Muslim chroniclers such as Ibn Kathir, the etymology was attributed to the mass conversion of two hundred thousand households in 971 AD, causing them to be named Turk Iman, which is a combination of "Turk" and "Iman" إيمان (faith, belief), meaning "believing Turks", with the term later dropping the hard-to-pronounce hamza.[12]

Historically, all of the Western or Oghuz Turks have been called Türkmen or Turkoman;[13] however, today the terms are usually restricted to two Turkic groups: the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan and adjacent parts of Central Asia, and the Turkomans of Iraq and Syria.

The modern Turkmen people descend, at least in part, from the Oghuz Turks of Transoxiana, the western portion of Turkestan, a region that largely corresponds to much of Central Asia as far east as Xinjiang. Oghuz tribes had moved westward from the Altay mountains in the 7th century AD, through the Siberian steppes, and settled in this region. They also penetrated as far west as the Volga basin and the Balkans. These early Turkmens are believed to have mixed with native Sogdian peoples and lived as pastoral nomads until the Russian invasion of the 19th century.[14]

History

Turkmens in Iran

Signs of advanced settlements have been found throughout Turkmenistan including the Djeitun settlement where neolithic buildings have been excavated and dated to the 7th millennium BCE.[15] By 2000 BCE, various Indo-European peoples began to settle throughout the region, as indicated by the finds at the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. Notable early tribes included the nomadic Dahae (a.k.a. Daoi/Dasa), Massagetae and Scythians. The Achaemenid Empire annexed the area by the 4th century BCE and then lost control of the region following the invasion of Alexander the Great, whose Hellenistic influence had an impact upon the area and some remnants have survived in the form of a planned city which was discovered following excavations at Antiocheia (Merv). The Parni, a Dahae tribe came to dominate the region, and established the Parthian Empire, which also later fractured as a result of invasions from the north.

Ephthalites, Huns, and Göktürks came in a long parade of invasions. Finally, the Sassanid Empire based in Persia ruled the area prior to the coming of the Muslim Arabs during the Umayyad Caliphate by 716 CE. The majority of the inhabitants were converted to Islam as the region grew in prominence. Next came the Oghuz Turks, who imparted their language upon the local population. A tribe of the Oghuz, the Seljuks, established a Turko-Iranian culture that culminated in the Khwarezmid Empire by the 12th century. Mongol hordes led by Genghis Khan conquered the area between 1219 and 1221 and devastated many of the cities which led to a rapid decline of the remaining Iranian urban population.

The Turkmen largely survived the Mongol period due to their semi-nomadic lifestyle and became traders along the Caspian, which led to contacts with Eastern Europe. Following the decline of the Mongols, Tamerlane conquered the area and his Timurid Empire would rule, until it too fractured, as the Safavids, Khanate of Bukhara, and Khanate of Khiva all contested the area. The expanding Russian Empire took notice of Turkmenistan's extensive cotton industry, during the reign of Peter the Great, and invaded the area. Following the decisive Battle of Geok Tepe in January 1881, Turkmenistan became a part of the Russian Empire. After the Russian Revolution, Soviet control was established by 1921 as Turkmenistan was transformed from a medieval Islamic region to a largely secularized republic within a totalitarian state. By 1991, with the fall of the Soviet Union, Turkmenistan achieved independence as well, but remained dominated by a one-party system of government led by the authoritarian regime of President Saparmurat Niyazov until his death in December 2006.

Language

Turkmen (Latin: Türkmençe, Cyrillic: Түркменче) is the language of the titular nation of Turkmenistan. It is spoken by over 5,200,000 people in Turkmenistan, and by roughly 3,000,000 people in other countries, including Iran, Afghanistan, and Russia.[16] Up to 30% of native speakers in Turkmenistan also claim a good knowledge of Russian, a legacy of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union.

Turkmen is not a literary language in Iran and Afghanistan, where many Turkmen tend towards bilingualism, usually conversant in the countries' different dialects of Persian, such as Dari in Afghanistan. Variations of the Persian alphabet are, however, used in Iran.

Ethnogenesis

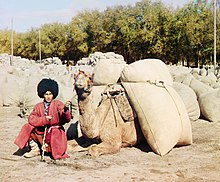

A Turkmen man of Turkmenistan in traditional clothes by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, around 1910.[17][18][19]

Turkmens in 1890

Turkmens in Merv, 1890

Genetic studies on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) restriction polymorphism confirmed that Turkmen were characterized by the presence of local Iranian mtDNA lineages, similar to the Eastern Iranian populations, but high male Mongoloid genetic component observed in Turkmens populations with the frequencies of about 20%.[20] This most likely indicates an ancestral combination of Turkic and Iranian groups that the modern Turkmen have inherited and which appears to correspond to the historical record which indicates that various Iranian tribes existed in the region prior to the migration of Turkic tribes:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The Turkomans observe a difference between their children from Turkoman mothers, and those from the Persian female captives whom they take as wives, and the Kazakh women whom they purchase from the Uzbeks of Khiva. The Turkomans of pure race enjoy full privileges, while the others are not allowed to contract marriages with Turkoman women of pure blood, but must choose themselves wives among the half-castes and Kazakh captives.

As there exists a great animosity between the Yamuds and Goklans they do not intermarry, although they reckon themselves of equally noble lineage. The same hatred is extended to the Tekke Turkomans, whom the Goklans and Yamuds, moreover, look upon as their inferiors, being, according to their genealogies, the descendants of a slave-woman, whilst they are the posterity of a free-woman. (p. 71)

The more intimate connection of the Astrakhan and Kazan Tartars with the Mogols can be traced in their features; with the Nogay it is less visible. In like manner, the Turkomans further off in the desert, and the Uzbeks of Khive, have more of the Mogol expression than the Turkomans who encamp near the Persian frontier. The frequent intercourse of the Nogay, in latter years, with the Cherkess, seems to have improved their race; and notwithstanding the enmity that exists between the Turkomans and the Persians, it is still not unlikely that their close vicinity should have produced on the former a similar effect in a lapse of several centuries. The fact we have seen, that the Turkomans marry Persian women, when they take them as prisoners. The Turkoman women are, like the men, tall, and when young, well-shaped; their faces are rounder than those of the men; the cheek-bones less prominent; the eyes black, with fine eye-brows, and many with fair complexion; the nose is rather flat; the mouth small, with a row of regular white teeth. In a word, a great number of the younger part of the community might be reckoned as fair specimens of pretty women. (p. 73)

Bode, C.A. "The Yamud and Goklan tribes of Turkomania". Journal of the London Ethnological Society, vol. 1, 1848, pp. 60–78.

Religion

The Turkmen of Turkmenistan, like their kin in Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Iran are predominantly Muslims. According to the CIA World Factbook, Turkmenistan is 89% Muslim and 10% Eastern Orthodox. Most ethnic Russians are Orthodox Christians. The remaining 1% is unknown. A 2009 Pew Research Center report indicates a higher percentage of Muslims with 93.1% of Turkmenistan's population adhering to Islam.

The great majority of Turkmen readily identify themselves as Muslims and acknowledge Islam as an integral part of their cultural heritage. However, there are some who only support a revival of the religion's status merely as an element of national revival.

Culture and society

Nomadic heritage

Tekke chuval with Salor güls, late 19th century

Before the establishment of Soviet power in Central Asia, it was difficult to identify distinct ethnic groups in the region. Sub-ethnic and supra-ethnic loyalties were more important to people than ethnicity. When asked to identify themselves, most Central Asians would name their kin group, neighborhood, village, religion or the state in which they lived; the idea that a state should exist to serve an ethnic group was unknown.[21]

Most Turkmen were nomads and were not settled in cities and towns until the advent of the Soviet government. This mobile lifestyle precluded identification with anyone outside one's kin group and led to frequent conflicts between different Turkmen tribes. In collaboration with the local nationalists, the Soviet government sought to transform the Turkmen and other “backward” ethnic groups in the USSR into modern socialist nations that based their identity on a fixed territory and a common language.

The Soviet-led standardization of the Turkmen language, education, and projects to promote ethnic Turkmen in the industry, government and higher education had led growing numbers of Turkmen to identify with a larger national Turkmen culture rather than with sub-national, pre-modern forms of identity.[22] Before the Soviet era, a proverb stated that the Turkmen’s home was where his horse happened to stand. After gaining independence from the Soviet Union, Turkmen historians went to great lengths to prove that the Turkmen had inhabited their current territory since time immemorial; some historians even tried to deny the nomadic heritage of the Turkmen.[23]

Tolkuchka Bazaar in Turkmenistan

Turkmen lifestyle was heavily invested in horsemanship and as a prominent horse culture, Turkmen horse-breeding was an ages old tradition. In spite of changes prompted by the Soviet period, a tribe in southern Turkmenistan has remained very well known for their horses, the Akhal-Teke desert horse – and the horse breeding tradition has returned to its previous prominence in recent years.[24]

Many tribal customs still survive among modern Turkmen. Unique to Turkmen culture is kalim which is a groom's "dowry", that can be quite expensive and often results in the widely practiced[citation needed] tradition of bridal kidnapping.[25] In something of a modern parallel, in 2001, President Saparmurat Niyazov had introduced a state enforced "kalim", which required all foreigners who wanted to marry a Turkmen woman to pay a sum of no less than $50,000.[26] The law was abolished in March 2005.[27]

Other customs include the consultation of tribal elders, whose advice is often eagerly sought and respected. Many Turkmen still live in extended families where various generations can be found under the same roof, especially in rural areas.[25]

The music of the nomadic and rural Turkmen people reflects rich oral traditions, where epics such as Koroglu are usually sung by itinerant bards. These itinerant singers are called bakshy and sing either a cappella or with instruments such as the two-stringed lute called dutar.

Society today

Girls in Turkmenistan in 2011

Since Turkmenistan's independence in 1991, a cultural revival has taken place with the return of a moderate form of Islam and celebration of Novruz (an Iranian[28] tradition) or New Year's Day.

Turkmen can be divided into various social classes including the urban intelligentsia and workers whose role in society is different from that of the rural peasantry. Secularism and atheism remain prominent for many Turkmen intellectuals who favor moderate social changes and often view extreme religiosity and cultural revival with some measure of distrust.[29]

Self-proclaimed President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov was largely responsible for many of the changes that have taken place in modern Turkmen society. Niyazov made nationalism an important element in Turkmenistan, while contacts with Turkmen in neighboring Iran and Afghanistan have increased. Significant changes to the names of the cities as well as calendar reform were introduced by President Niyazov as well. The calendar reform resulted in renaming months and days of the week from Persian or European-derived words into purely Turkmen ones, some of them eponymously related to the president or his family. The policy was reversed in 2008.[30]

The five traditional carpet designs that form motifs in the country's state emblem and flag represent the five major Turkmen tribes.

Iranian Muslim Turkmen from Ashuradeh

A Turkmen girl and baby from Afghanistan

A Turkmen man from Turkmenistan

Turkmen in Iran

Turkmen rulers, successively of the Black Sheep Turkomans and White Sheep Turkomans, ruled much of Persia and surrounding countries before Shah Ismail I defeated them to begin the Safavid dynasty in 1501. Tabriz was their usual capital. There remains a relatively small population identifying as Turkmen in modern Iran.

Turkmen in Afghanistan

Turkmen are another Sunni Turkic-speaking group whose language has close affinities with modern Turkish. The Afghan Turkmen population in the 1990s was estimated at around 200,000. Turkmen also reside north of the Amu Darya in Turkmenistan.[31] The original Turkmen groups came from east of the Caspian Sea into northwestern Afghanistan at various periods, particularly after the end of the nineteenth century when the Russians moved into their territory. They established settlements from Balkh Province to Herat Province, where they are now concentrated; smaller groups settled in Kunduz Province. Others came in considerable numbers as a result of the failure of the Basmachi revolts against the Bolsheviks in the 1920s.[31] Turkmen tribes, of which there are twelve major groups in Afghanistan, base their structure on genealogies traced through the male line. Senior members wield considerable authority. Formerly a nomadic and warlike people feared for their lightning raids on caravans, Turkmen in Afghanistan are farmer-herdsmen and important contributors to the economy. They brought karakul sheep to Afghanistan and are also renowned makers of carpets, which, with karakul pelts, are major hard currency export commodities. Turkmen jewelry is also highly prized.[31]

Turkmen of Stavropol Region of Russia

In the Stavropol Region of southern Russia, there is a long established colony of Turkmen. They are often referred to as Trukhmen by the local ethnic Russian population, and sometimes use the self-designation Turkpen.[32] According to the 2010 Census of Russia, they numbered 15,048, and accounted for 0.5% of the total population of Stavropol Region.

The Turkmens are said to have migrated into the Caucasus in the 17th century, in particular in the Mangyshlak region. These migrants belonged mainly to the Chaudorov (Chavodur), Sonchadj and Ikdir tribes. The early settlers were nomadic but over time a process of sedentarization took place. In their cultural life the Trukhmens of today differ very little from their neighbours and are now settled farmers and stockbreeders.[32]

Although the Turkmen language belongs to the Oghuz group of Turkic languages, in Stavropol it has been strongly influenced by the Nogai language, which belongs to the Kipchak group. The phonetic system, grammatical structure and to some extent also the vocabulary, have been somewhat influenced.[33]

Demographics and population distribution

CIA map showing the territory of the settlement of ethnic groups and subgroups in Afghanistan (2005)

The Turkmen people of Central Asia live in:

Turkmenistan, where some 85% of the population of 5,042,920 people (July 2006 est.), are ethnic Turkmen. In addition, an estimated 1,200 Turkmen refugees from northern Afghanistan currently reside in Turkmenistan due to the ravages of the Soviet–Afghan War and factional fighting in Afghanistan which saw the rise and fall of the Taliban.[34]

Afghanistan, where as of 2006, 200,000 are ethnic Turkmen and are largely concentrated primarily along the Turkmen-Afghan border in the provinces of Faryab, Jowzjan, Samangan and Baghlan. There are also other communities in Balkh and Kunduz Provinces.

Iran, where about 1,328,585 Turkmen are primarily concentrated in the provinces of Golestān and North Khorasan.[2]

Pakistan, During the Soviet–Afghan war, Some Turkmen fled the country and settled in neighboring Pakistan. Today a small population of Turkmen reside in Pakistan mainly in Peshawar city. Their number in Pakistan is estimated to be less than 5,000. They are mainly involved in Carpet Business in Peshawar city.

Turkey, where most Turkmens have integrated into sedentary life over the centuries through Seljuk and Ottoman periods. A considerable nomadic Turkmen group called Yörük still maintain their lifestyle in Anatolia and parts of the Balkans.

Y-DNA haplogroups of Turkmens

Recent studies on the Turkmens of Iran and Afghanistan suggest that haplogroup Q is the dominant Y-DNA in Turkmens. So far, there have been two detailed studies on the Y-DNA of Turkmens.

- One piece of research (Cristofaro et al.,2013) found that the Turkmens in Afghanistan have 31.1% Q-M25 (Q1a2, in the 2017 ISOGG phylogeny) and 2.7% Q-M346 (Q total 25/74=33.8%), followed by R1a1a/R-M198 at 16.2%, also R1b 2.74%, R2 1.4%), J1c3 (J-Page8; 8.1%, also other various J-subclades at 9.5%), N1b/N-P43 (6.8%), G2a/G-P303 (4.1%), L1a/L-M76 (4.1%), and various subgroups of E1b1b 5.4%, O3 (KL2, M134) 2.7%, C(M401) 1.4%, H(M69*) 1.4%.[35]

- Another study (Grugni et al.,2012) found that 42.6% (29/68) of Iranian Turkmens (in Golestan) have haplogroup Q-M25, followed by R1a1a/R-M198 (14.5%, also R1b 4.3%, R2 1.4%), J1c3/J-Page8 (5.8%, also other various J-subclades at 8.8%), G2a (5.8%), L3/L-M357 (5.8%), E1b1b (4.3%), NO (2.9%, xN, xO), H (1.4%), T (1.4%).[36]

The above studies suggest that there is a strong possibility that the precursors of the Turkmen, such as the Oghuz, belonged to Q-M25 .

This is supported by circumstantial evidence that the elites of many pre-modern dynasties from Inner Asia belonged to Haplogroup Q, including Q-M25.

- In 2015, three sets of male remains from c. 1300 CE were recovered from a royal tomb at Shuzhuanglou, northern Hebei China. The principal occupant was known to be Korguz, King (Gaodang) 高唐王=趙王 阔里吉思 of the Mongol Ongud (汪古部) tribe,[37] and a descendant of the Turkic Shatuo 沙陀族 tribe – a component of the Gokturk Western Turkic Khaganate. All three males were found to belong to haplogroup Q (subclade unknown). Korguz's mtDNA fell into haplogroup D4m2 and the others into haplogroup A.[38]

- Males of the Ashina clan (阿史那) that ruled the Gokturks and Khazaria may also have belonged to haplogroup Q-M346 (Q1b).[39]

- The elite of the Xiongnu, who were also dominated by haplogroup Q, are also widely believed to have been a Turkic people. For example, in the ancient cemetery in Heigouliang (Xinjiang), which was known as the summer palace of the Xiongnu king, the remains of all 12 males found belonged to haplogroup Q, including four who belonged to Q-M346 (Q1b) and appeared to have been the hosts of the tombs concerned.[40] Xiongnu nobles/conquerors found in another ancient site belonged to Q-M3.[41]

See also

- Turkmen Sahra

References

^ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 18 March 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Ethnologue". Retrieved 8 August 2018.

^ "Ethnic Groups". Library of Congress Country Studies. 1997. Retrieved 2010-10-08.

^ Jump up to: a b

^ Alisher Ilhamov (2002). Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan. Open Society Institute: Tashkent.

^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "UNHCR - The UN Refugee Agency" (PDF). www.unhcr.org.

^ 2002 Russian census

^ 2002 Tajikistani census (2010)

^ "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

^ "UCLA Language Materials Project: Main". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ Yu. Zuev, "Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology", Almaty, Daik-Press, 2002, p. 157,

ISBN 9985-4-4152-9

^ "Turkmenistan : Country Studies – Federal Research Division, Library of Congress". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "البداية والنهاية/الجزء الحادي عشر". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^

Glenn E. Curtis, ed. "Origins and Early History", Turkmenistan: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1996. pg. 13

^ Amazon.com: Central Asians under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change (Cornell Paperbacks): Elizabeth E. Bacon, Michael M. J. Fischer: Books. ISBN 9780801492112.

^ "Cambridge Journals Online – Antiquity" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "Turkmen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "Turkmen Camel Driver by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "Turkmen Man Posing with Camel Loaded with Sacks, Probably of Grain or Cotton, Central Asia". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ Prokudin-Gorskii. "Prokudin-Gorsky, other". Šechtl & Voseček. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "1 Russian Journal of Genetics, Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphism in Populations of the Caspian Region and Southeastern Europe". Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

^ Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781400844296.

^ Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9781400844296.

^ Adrienne Lynn Edgar (2007). Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan. Princeton University Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781400844296.

^ "Turkmenistan Embassy Washington". www.turkmenistanembassy.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-27.

^ ab "Turkmen Society". Archived from the original on 2007-03-18.

^ Philip Sherwell, Price of loving a Turkmen girl is now $50,000, The Telegraph, July 22, 2001

^ Gulnoza Saidazimova, Turkmenistan: Marriage Gets Cheaper As Turkmenbashi Drops $50,000 Dollar Foreigners' Fee, Radio Free Europe, June 10, 2005

^ Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, "Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index ", Taylor & Francis, 2006. pp 605: "Buyid rulers such as Azud al-Dawla resusciated a number of pre-islamic Iranian practices, most notably the titular of shahanshah (king of kings) and the celebration of the Persian New Year

^ "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Turkmenistan: Social Structure". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ "BBC NEWS – Asia-Pacific – Turkmen go back to old calendar". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

^ abc "US Library of Congress Country Studies-Afghanistan: Turkmen".

^ ab The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Eki.ee. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2013-07-12.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "UNHCR Begins Compiling Database of Refugees in Turkmenistan". Archived from the original on 2005-12-08.

^ J D Cristofaro et al., 2013, "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge"

^ Viola Grugni et al.,2012, "Ancient Migratory Events in the Middle East: New Clues from the Y-Chromosome Variation of Modern Iranians" It seems that more correctly rounded frequency-figures might be 14.7%(instead of 14.5%), 5.9% (instead of 5.8%), 4.4% (instead of 4.3%), 1.5% (instead of 1.4%).

^ Qui, Y; et al. (2015). "Identification of kinship and occupant status in Mongolian noble burials of the Yuan Dynasty through a multidisciplinary approach". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B370 (1660): 20130378. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0378. PMC 4275886.

^ Korguz, who died in 1298 and was reburied at Shuzhuanglou in 1311, was a maternal grandson of Kublai Khan (元世祖), should not be confused with Korguz, King of the Uyghurs, d. 1242). Korguz, King of the Ongud was prominent in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of China and founded three dynasties. Both of Korguz's consorts were princesses of the Yuan Dynasty and granddaughters of Kublai Khan. It was important for the Yuan Dynasty to maintain marriage alliances with the Ongud which had been a very important ally the time of since Genghis Khan. About 16 princesses of the Yuan Dynasty were married to kings of the Ongud tribe.

^ "Family Tree DNA - Genetic Testing for Ancestry, Family History & Genealogy". www.familytreedna.com.

^ Y-Chromosome Genetic Diversity of the Ancient North Chinese populations, Li Hongjie, Jilin University-China, 2012

^ Y chromosomes of ancient Hunnu people and its implication on the phylogeny of East Asian linguistic families. LL. Kang et al., 2013

Sources

- Bacon, Elizabeth E. Central Asians Under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change, Cornell University Press (1980).

ISBN 0-8014-9211-4. - Turkmenistan Pages by Ekahau

- Did the engsi hang inside or outside the yurt?

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkmens. |

. Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 468.

. Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 468.