Electorate of Hesse

Electorate of Hesse Kurfürstentum Hessen | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1803–1807 1814–1866 | |||||||||||||

Flag  Coat of arms (1818) | |||||||||||||

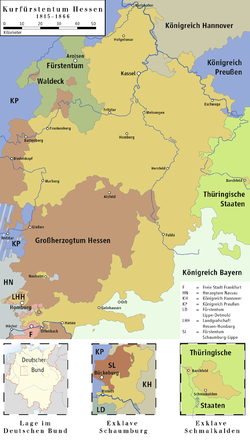

Hesse-Kassel in 1866 | |||||||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire State of the German Confederation | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Kassel | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | German | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Protestant (Calvinist) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Elector of Hesse | |||||||||||||

• 1803–1821 | William I, Elector of Hesse | ||||||||||||

• 1821–1847 | William II, Elector of Hesse | ||||||||||||

• 1847–1866 | Frederick William, Elector of Hesse | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 1803 | ||||||||||||

• Raised to Electorate | 1803 | ||||||||||||

• Annexed by Kingdom of Westphalia | 1807 | ||||||||||||

• Reestablished | 1814 | ||||||||||||

• Annexed by Kingdom of Prussia | 1866 | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 1864 | 9,581 km2 (3,699 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1864 | 745063 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Hesse-Kassel thaler (to 1858) Hesse-Kassel vereinsthaler (1858–1873) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Electorate of Hesse (German: Kurfürstentum Hessen), also known as Hesse-Kassel or Kurhessen, was a state elevated by Napoleon in 1803 from the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel. When the Holy Roman Empire was abolished in 1806, the Prince-Elector of Hesse chose to remain an Elector, even though there was no longer an Emperor to elect. In 1807, with the Treaties of Tilsit, the area was annexed to the Kingdom of Westphalia, but in 1814, the Congress of Vienna restored the electorate.

The state was the only electorate within the German Confederation. It consisted of several detached territories to the north of Frankfurt, which survived until the state was annexed by Prussia in 1866 following the Austro-Prussian War. It comprised a total land area of 3,699 square miles (9,580 km2), and its population in 1864 was 745,063.

History

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel originated in 1567 with the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse between the heirs of Philip I of Hesse ("the Magnanimous") after his death. Philip's eldest son, William IV, received Hesse-Kassel, which comprised about half the area of the Landgraviate of Hesse, including the capital, Kassel. William's brothers received Hesse-Marburg and Hesse-Rheinfels, but their lines died out within a generation and the territories then reverted to Hesse-Kassel and to the Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt.

The reign of the Landgrave William IX was an important epoch in the history of Hesse-Kassel. Ascending the throne in 1785, he took part in the War of the First Coalition against French First Republic a few years later, but in 1795 the Peace of Basel was signed. In 1801 he lost his possessions on the left bank of the Rhine, but in 1803 he was compensated for these losses with some former French territory round Mainz, and at the same time he was raised to the dignity of Prince-elector (Kurfürst) William I, a title he retained even after the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire.[1]

In 1806, William I signed a treaty of neutrality with Napoleon Bonaparte, but after the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, the latter, suspecting William's designs, occupied his country and expelled him. Hesse-Kassel was then incorporated to the Kingdom of Westphalia under the rule of Jérôme Bonaparte.

After the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, the French were driven out of Hesse-Kassel, and on 21 November, the Elector returned in triumph to his capital, Kassel. A treaty concluded by him with the Coalition (2 December) stipulated that he was to receive back all his former territories, or their equivalent, and at the same time restored the ancient constitution of his country. This treaty, so far as the territories were concerned, was implemented by the Great Powers at the Congress of Vienna. They refused, however, the Elector's request to be recognized as "King of the Chatti" (König der Katten). At the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), he was listed with the grand dukes as a "Royal Highness."[2] William chose to retain the now empty title of prince-elector, with the predicate of "Royal Highness".[1]

William I had marked his restoration by abolishing with a stroke of the pen all the reforms introduced under the French regime, repudiating the Westphalian debt and declaring null and void the sale of the crown domains. Everything was set back to its condition on 1 November 1806; even the officials had to descend to their former rank, and the army to revert to the old uniforms and powdered pigtails.[1]

The Estates (Parliament), indeed, were summoned in March 1815, but the attempt to devise a constitution broke down; their appeal to the Federal Assembly Bundesversammlung at Frankfurt to call the Elector to order in the matter of the debt and the domains came to nothing, owing to the intervention of Klemens von Metternich; and in May 1816 the Estates were dissolved.[1]

William I died on 27 February 1821 and was succeeded by his son, William II. Under him, the constitutional crisis in Kassel came to a head. He was arbitrary and avaricious, like his father, and moreover shocked public sentiment by his treatment of his wife, a popular Prussian princess, and his relations with his mistress, one Emilie Ortlöpp, whom he created Countess of Reichenbach-Lessonitz and loaded with wealth.[1]

The July Revolution in Paris gave the signal for disturbances; William II was forced to summon the Estates, and on 6 January 1831, a constitution on the ordinary Liberal basis[clarification needed] was signed. The Elector now retired to Hanau, appointed his son Frederick William as regent, and took no further part in public affairs.[1]

Frederick William, without his father's coarseness, had a full share of his arbitrary and avaricious temper. Constitutional restrictions were intolerable to him; and the consequent friction with the Diet (lower house) was aggravated when, in 1832, Hans Hassenpflug was placed at the head of the administration. All the efforts of William II and his minister were directed to nullifying the constitutional controls vested in the Diet; and the Opposition was fought by manipulating the elections, packing the judicial bench, and a vexatious and petty persecution of political "suspects", and this policy continued after the retirement of Hassenpflug in 1837.[1]

Coat of arms in 1846

The consequences emerged in the revolutionary year 1848 in a general manifestation of public discontent; and Frederick William, who had become Elector on his father's death (20 November 1847), was forced to dismiss his reactionary ministry and to agree to a comprehensive programme of democratic reform. This, however, was short lived. After the breakdown of the Frankfurt National Parliament, Frederick William joined the Prussian Northern Union, and deputies from Hesse-Kassel were sent to the Erfurt Parliament. But as Austria recovered strength, the Elector's policy changed.[1]

On 23 February 1850, Hassenpflug was again placed at the head of the administration and threw himself with renewed zeal into the struggle against the constitution and into opposition to the Kingdom of Prussia. On 2 September, the Diet was dissolved; the taxes were continued by Electoral ordinance; and the country was placed under martial law. It was at once clear, however, that the Elector could not depend on his officers or troops, who remained faithful to their oath to the constitution. Hassenpflug persuaded the Elector to leave Kassel secretly with him, and on 15 October, appealed for aid to the reconstituted federal diet, which willingly passed a decree of "intervention". On 1 November an Austrian and Bavarian force marched into the Electorate.[1]

This was a direct challenge to Prussia, which under conventions with the Elector had the right to use the military roads through Hesse that were her sole means of communication with her exclaves in the Rhine provinces. War seemed imminent; Prussian troops also entered the country, and shots were exchanged between the outposts. But Prussia was in no condition to take up the challenge; and the diplomatic contest that followed resulted in the Austrian triumph at Olmütz (1851). Hesse was surrendered to the federal diet; the taxes were collected by the federal forces, and all officials who refused to recognize the new order were dismissed.[1]

In March 1852, the federal diet abolished the constitution of 1831, together with the reforms of 1848, and in April issued a new provisional constitution, under which the new diet had very narrow powers; and the elector was free to carry out his policy of amassing money, forbidding the construction of railways and factories, and imposing strict orthodoxy on churches and schools. In 1855, however, Hassenpflug who had returned with the Elector was dismissed; and five years later, after a period of growing agitation, a new constitution was granted with the consent of the federal diet (30 May 1860).[1]

The new chambers demanded the constitution of 1831; and, after several dissolutions which always resulted in the return of the same members, the federal diet decided to restore the constitution of 1831 (14 May 1862). This had been due to a threat of Prussian occupation; and it needed another such threat to persuade the Elector to reassemble the chambers, which he had dismissed at the first sign of opposition; and he revenged himself by refusing to transact any public business.[1]

In 1866, the end came. The elector, Frederick William, full of grievances against Prussia, threw in his lot with Austria; the electorate was at once overrun with Prussian troops; Kassel was occupied (20 June); and the Elector was taken as a prisoner to Stettin. By the Peace of Prague, Hesse-Kassel was annexed to Prussia. The elector Frederick William (d. 1875) had been, by the terms of the treaty of cession, guaranteed the entailed property of his house. This was, however, sequestered in 1868 owing to his intrigues against Prussia; part of the income was paid, however, to the eldest agnate, the landgrave Frederick (d. 1884), and part, together with certain castles and palaces, was assigned to the also dispossessed cadet lines of Hesse-Philippsthal and Hesse-Philippsthal-Barchfeld.[1]

References

^ abcdefghijklm Chisholm 1911, p. 411.

^ Satow, Ernest Mason (1932). A Guide to Diplomatic Practice. London: Longmans..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

![]() Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 410–411.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 410–411.