Spanish Constitution of 1812

| Constitution of Cádiz | |

|---|---|

Original version of the Constitution kept in the Senate of Spain | |

| Cortes of Cádiz | |

| Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy | |

| Territorial extent | |

| Date passed | 19 March 1812 |

| Date enacted | 12 March 1812 |

| Signed by | President of the Cortes of Cádiz 174 deputies 4 secretaries |

| Date effective | 19 March 1812 (first time) 1 January 1820 (second time, de facto) 1836 (third time, de facto) |

| Date repealed | 4 May 1814 (first time) April 1823 (second time) 18 June 1837 (third time) |

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (Spanish: Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz (Spanish: Constitución de Cádiz) and as La Pepa,[1] was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest constitutions in world history.[2] It was established on 19 March 1812 by the Cortes of Cádiz, the first Spanish legislature. With the notable exception of proclaiming Roman Catholicism as the official and sole legal religion in Spain, the constitution was one of the most liberal of its time: it affirmed national sovereignty, separation of powers, freedom of the press, free enterprise, abolished feudalism, and established a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system. It was one of the first constitutions that allowed universal male suffrage, through a complex indirect electoral system.[3] It was repealed by King Ferdinand VII in 1814 in Valencia, who re-established absolute monarchy.

However, the Constitution had many difficulties becoming fully effective: much of Spain was ruled by the French, while the rest of the country was in the hands of interim Junta governments focused on resistance to the Bonapartes rather than on the immediate establishment of a constitutional regime. Many of the overseas territories did not recognize the legitimacy of these interim metropolitan governments, leading to a power vacuum and the establishment of separate juntas on the American continent. On 24 March 1814, six weeks after returning to Spain, Ferdinand VII abolished the constitution. The constitution was reinstated during the Trienio Liberal (1820–1823), and again briefly 1836—1837 while the Progressives prepared the Constitution of 1837.

Contents

1 Background

2 Deliberations and reforms

2.1 Establishment of Spanish active and passive citizenship

3 Repeal and restoration

4 See also

5 Bibliography

6 References

Background

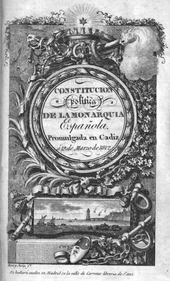

An original edition of the Constitution of 1812.

The Cortes drafted and adopted the Constitution while besieged by French troops, first on Isla de León (now San Fernando), then an island separated from the mainland by a shallow waterway on the Atlantic side of the Bay of Cádiz, and within the small, strategically located city of Cádiz itself.

From a Spanish point of view, the Peninsular War was a war of independence against the French Empire and the king installed by Napoleon, his brother Joseph Bonaparte. In 1808, both King Ferdinand VII and his predecessor and father, Charles IV, had resigned their claims to the throne in favor of Napoleon Bonaparte, who in turn passed the crown to his brother Joseph. While many in elite circles in Madrid were willing to accept Joseph's rule, the Spanish people were not. The war began on the night of 2 May 1808, and was immortalized by Francisco Goya's painting The Second of May 1808, also known as The Charge of the Mamelukes.

From the outbreak of the Spanish revolt against the Bonapartist regime in 1808, Napoleon's forces faced both Spanish armies and partisans, joined later by British and Portuguese armies under Arthur Wellesley. The Spanish organized an interim Spanish government, the Supreme Central Junta and called for a Cortes to convene with representatives from all the Spanish provinces throughout the worldwide empire, in order to establish a government with a firm claim to legitimacy. The Junta first met on 25 September 1808 in Aranjuez and later in Seville, before retreating to Cádiz.

The Supreme Central Junta, originally under the leadership of the elderly Count of Floridablanca, initially tried to consolidate southern and eastern Spain to maintain continuity for a restoration of the Bourbons. However, almost from the outset they were in physical retreat from Napoleon's forces, and the comparative liberalism offered by the Napoleonic regime made Floridablanca's enlightened absolutism[4] an unlikely basis to rally the country. In any event, Floridablanca's strength failed him and he died on 30 December 1808.

When the Cortes convened in Cádiz in 1810, there appeared to be two possibilities for Spain's political future if the French could be driven out. The first, represented especially by Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, was the restoration of the absolutist Antiguo Régimen ("Old Regime"); the second was to adopt some sort of written constitution.

Deliberations and reforms

Cortes of Cadiz Oath in 1810. Oil painting by José Casado del Alisal, 1863.

Retreating before the advancing French and an outbreak of yellow fever, the Supreme Central Junta moved to Isla de León, where it could be supplied and defended with the help of the Spanish and British navies, and abolished itself, leaving a regency to rule until the Cortes could convene.

The origins of the Cortes did not harbor any revolutionary intentions, since the Junta saw itself simply as a continuation of the legitimate government of Spain. The opening session of the new Cortes was held on 24 September 1810 in the building now known as the Real Teatro de las Cortes. The opening ceremonies included a civic procession, a mass, and a call by the president of the Regency, Pedro Quevedo y Quintana, the bishop of Ourense, for those present to fulfill their task loyally and efficiently. Still, the very act of resistance to the French involved a certain degree of deviation from the doctrine of royal sovereignty: if sovereignty resided entirely in the monarch, then Charles and Ferdinand's abdications in favor of Napoleon would have made Joseph Bonaparte the legitimate ruler of Spain.[5]

Allegory of the Constitution of 1812, Francisco de Goya, Swedish National Museum.

The representatives who gathered at Cádiz were far more liberal than the elite of Spain taken as a whole, and they produced a document far more liberal than might have been produced in Spain were it not for the war. Few of the most conservative voices were at Cádiz, and there was no effective communication with King Ferdinand, who was a virtual prisoner in France. In the Cortes of 1810–1812, liberal deputies, who had the implicit support of the British who were protecting the city, were in the majority and representatives of the Church and nobility constituted a minority. Liberals wanted equality before the law, a centralized government, an efficient modern civil service, a reform of the tax system, the replacement of feudal privileges by freedom of contract, and the recognition of the property owner's right to use his property as he saw fit. Three basic principles were soon ratified by the Cortes: that sovereignty resides in the nation, the legitimacy of Ferdinand VII as king of Spain, and the inviolability of the deputies. With this, the first steps towards a political revolution were taken, since prior to the Napoleonic intervention, Spain had been ruled as an absolute monarchy by the Bourbons and their Habsburg predecessors. Although the Cortes was not unanimous in its liberalism, the new Constitution reduced the power of the crown, the Catholic Church (although Catholicism remained the state religion), and the nobility.

The promulgation of the Constitution of 1812, oil painting by Salvador Viniegra (Museo de las Cortes de Cádiz).

The Cortes of Cádiz worked feverishly and the first written Spanish constitution was promulgated in Cádiz on 19 March 1812. The Constitution of 1812 is regarded as the founding document of liberalism in Spain and one of the first examples of classical liberalism or conservative liberalism worldwide. It came to be called the "sacred code" of the branch of liberalism that rejected a part of the French Revolution, and during the early nineteenth century it served as a model for liberal constitutions of several Mediterranean and Latin American nations. It served as the model for the Norwegian Constitution of 1814, the Portuguese Constitution of 1822 and the Mexican one of 1824, and was implemented with minor modifications in various Italian states by the Carbonari during their revolt of 1820 and 1821.[6]

As the principal aim of the new constitution was the prevention of arbitrary and corrupt royal rule, it provided for a limited monarchy which governed through ministers subject to parliamentary control. Suffrage, which was not determined by property qualifications, favored the position of the commercial class in the new parliament, since there was no special provision for the Church or the nobility.[7] The constitution set up a rational and efficient centralized administrative system for the whole monarchy based on newly reformed and uniform provincial governments and municipalities, rather than maintaining some form of the varied, historical local governmental structures. Repeal of traditional property restrictions gave liberals the freer economy they wanted.

Anguita, where the act was signed to establish the first diputación provincial under the 1812 Constitution.

The first provincial government created under the Constitution was in the province of Guadalajara con Molina. Its deputation first met in the village of Anguita in April 1813, since the capital Guadalajara was the site of ongoing fighting.

Establishment of Spanish active and passive citizenship

Constitution of 1812 monument in St. Augustine, Florida. This obelisk was erected when the city was the capital of the Spanish Florida.

Among the most debated questions during the drafting of the constitution was the status of the native and mixed-race populations in Spain's possessions around the world. Most of the overseas provinces were represented, especially the most populous regions. Both the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru had deputies present, as did Central America, the islands of the Spanish Caribbean, Florida, Chile, Upper Peru and the Philippines.[8] The total number of representatives was 303, of which thirty-seven were born in overseas territories, although several of these were temporary, substitute deputies [suplentes] elected by American refugees in the city of Cadiz: seven from New Spain, two from Central America, five from Peru, two from Chile, three from the Río de la Plata, three from New Granada, and two from Venezuela, one from Santo Domingo, two from Cuba, one from Puerto Rico and two from the Philippines.[9] Although most of the overseas representatives were Criollos, the majority wanted to extend suffrage to all indigenous, mixed-race and free black people of the Spanish Empire, which would have granted the overseas territories a majority in the future Cortes. The majority of representatives from peninsular Spain opposed those proposals as they wished to limit the weight of non-peninsulares. According to the best estimates of the time, continental Spain had an estimated population of between 10 and 11 million, while the overseas provinces had a combined population of around 15 to 16 million.[10] The Cortes ultimately approved a distinction between nationality and citizenship (that is, those with the right to vote).

The Constitution gave Spanish citizenship to natives of the territories that had belonged to the Spanish monarchy in both hemispheres.[11] The Constitution of 1812 included Indigenous peoples of the Americas to Spanish citizenship, but the acquisition of citizenship for any casta of Afro-American peoples of the Americas was through naturalization excluding slaves. Spanish nationals were defined as all people born, naturalized or permanently residing for more than ten years in Spanish territories.[12] Article 1 of the Constitution read: "The Spanish nation is the collectivity of the Spaniards of both hemispheres."[13] Voting rights were granted to Spanish nationals whose ancestry originated from Spain or the territories of the Spanish Empire.[14] This had the effect of changing the legal status of the people not only in peninsular Spain but in Spanish possessions overseas. In the latter case, not only people of Spanish ancestry but also indigenous peoples as well were transformed from the subjects of an absolute monarch to the citizens of a nation rooted in the doctrine of national, rather than royal, sovereignty.[15] At the same time, the Constitution recognized the civil rights of free blacks and mulatos but explicitly denied them automatic citizenship. Furthermore, they were not to be counted for the purposes of establishing the number of representatives a given province was to send to the Cortes.[16] That had the effect of removing an estimated six million people from the rolls in the overseas territories. In part, this arrangement was a strategy by the peninsular deputies to achieve equality in the number of American and peninsular deputies in the future Cortes, but it also served the interests of conservative Criollo representatives, who wished to keep political power within a limited group of people.[17]

The peninsular deputies, for the most part, were also not inclined towards ideas of federalism promoted by many of the overseas deputies, which would have granted greater self-rule to the American and Asian territories. Most of the peninsulares, therefore, shared the absolutists' inclination towards centralized government.[18] Another aspect of the treatment of the overseas territories in the constitution —one of the many that would prove not to be to the taste of Ferdinand VII— that by converting these territories to provinces, the king was deprived of a great economic resource. Under the Antiguo Régimen, the taxes from Spain's overseas possessions went directly to the royal treasury; under the Constitution of 1812, it would go to the state administrative apparatus.

Spanish Nation map according to the Constitution of 1812.

The influence of the 1812 Constitution on the emerging states of Latin America was quite direct. Miguel Ramos Arizpe of Mexico, Joaquín Fernández de Leiva of Chile, Vicente Morales Duárez of Peru and José Mejía Lequerica of Ecuador, among other significant figures in founding American republics, were active participants at Cádiz. One provision of the Constitution, which provided for the creation of a local government (an ayuntamiento) for every settlement of over 1,000 people, using a form of indirect election that favored the wealthy and socially prominent, came from a proposal by Ramos Arizpe. This benefited the bourgeoisie at the expense of the hereditary aristocracy both on the Peninsula and in the Americas, where it was particularly to the advantage of the Criollos, since they came to dominate the ayuntamientos. It also brought in a certain measure of federalism through the back door, both on the peninsula and overseas: elected bodies at the local and provincial level might not always be in lockstep with the central government.

Repeal and restoration

Repeal of the Constitution of 1812 by Fernando VII in the palace of Cervellón, Valencia, Spain.

When Ferdinand VII was restored in March 1814 by the Allied Powers, it is not clear whether he immediately made up his mind as to whether to accept or reject this new charter of Spanish government. He first promised to uphold the constitution, but was repeatedly met in numerous towns by crowds who welcomed him as an absolute monarch, often smashing the markers that had renamed their central plazas as Plaza of the Constitution. Sixty-nine deputies of the Cortes signed the so-called Manifiesto de los Persas ("Manifesto of the Persians") encouraging him to restore absolutism. Within a matter of weeks, encouraged by conservatives and backed by the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy, he abolished the constitution on 4 May and arrested many liberal leaders on 10 May, justifying his actions as the repudiation of an unlawful constitution made by a Cortes assembled in his absence and without his consent. Thus he came back to assert the Bourbon doctrine that the sovereign authority resided in his person only.[19]

Ferdinand's absolutist rule rewarded the traditional holders of power—prelates, nobles and those who held office before 1808—but not liberals, who wished to see a constitutional monarchy in Spain, or many who led the war effort against the French but had not been part of the pre-war government. This discontent resulted in several unsuccessful attempts to restore the Constitution in the five years after Ferdinand's restoration. Finally on 1 January 1820 Rafael del Riego, Antonio Quiroga and other officers initiated a mutiny of army officers in Andalusia demanding the implementation of the Constitution. The movement found support among the northern cities and provinces of Spain, and by 7 March the king had restored the Constitution. Over the next two years, the other European monarchies became alarmed at the liberals' success and at the Congress of Verona in 1822 approved the intervention of royalist French forces in Spain to support Ferdinand VII. After the Battle of Trocadero liberated Ferdinand from control by the Cortes in August 1823, he turned on the liberals and constitutionalists with fury. After Ferdinand's death in 1833, the Constitution was in force again briefly in 1836 and 1837, while the Constitution of 1837 was being drafted. Since 1812, Spain has had a total of seven constitutions; the current one has been in force since 1978.

See also

- List of Constitutions of Spain

- Napoleonic Code

- Retroversion of the sovereignty to the people

- American Provincial Deputation of Spain

Bibliography

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy. Biblioteca Virtual "Miguel de Cervantes" on-line version of a partial translation originally published in Cobbett's Political Register, Vol. 16 (July–December 1814).- Artola, Miguel. La España de Fernando VII. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1999. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 84-239-9742-1

- Benson, Nettie Lee, ed. Mexico and the Spanish Cortes. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1966.

- Esdaile, Charles J. Spain in the Liberal Age. Oxford; Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2000.

ISBN 0-631-14988-0

- Harris, Jonathan, "An English utilitarian looks at Spanish American independence: Jeremy Bentham's Rid Yourselves of Ultramaria," The Americas 53 (1996), 217–233

- Herr, Richard, "The Constitution of 1812 and the Spanish Road to Constitutional Monarchy," pp. 65–102 (notes on pp. 374–380) in Isser Woloch, ed. Revolution and the Meanings of Freedom in the Nineteenth Century. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1996.

ISBN 0-8047-4194-8. (A volume in the publisher's series The Making of Modern Freedom.) - Lovett, Gabriel. Napoleon and the Birth of Modern Spain. New York: New York University Press, 1965.

- Rieu-Millan, Marie Laure. Los diputados americanos en las Cortes de Cádiz: Igualdad o independencia. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1990.

ISBN 978-84-00-07091-5

- Rodríguez O., Jaime E. The Independence of Spanish America. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

ISBN 0-521-62673-0

- Rodríguez, Mario. The Cádiz Experiment in Central America, 1808 to 1826. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

ISBN 978-0-520-03394-8

References

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: Constitución española de 1812 |

^ Because it was passed by the Cortes on the day of Saint Joseph (in Spanish, Pepe is an informal nickname for "José").

^ "¡Viva la Pepa! 1812, las Cortes de Cádiz y la primera Constitución Española" (in Spanish). National Geographic España. 17 March 2016.

^ "Constitución de 1812" (in Spanish). Congress of Deputies.

^ Charles J. Esdaile, Spain in the Liberal Age, Blackwell, 2000.

ISBN 0-631-14988-0. p. 22.

^ Charles J. Esdaile, Spain in the Liberal Age, Blackwell, 2000.

ISBN 0-631-14988-0. p. 19–20.

^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). A History of Spain and Portugal: Eighteenth Century to Franco. 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-299-06270-5.The Spanish pattern of conspiracy and revolt by liberal army officers ... was emulated in both Portugal and Italy. In the wake of Riego's successful rebellion, the first and only pronunciamiento in Italian history was carried out by liberal officers in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The Spanish-style military conspiracy also helped to inspire the beginning of the Russian revolutionary movement with the revolt of the Decembrist army officers in 1825. Italian liberalism in 1820–1821 relied on junior officers and the provincial middle classes, essentially the same social base as in Spain. It even used a Hispanized political vocabulary, for it was led by giunte (juntas), appointed local capi politici (jefes políticos), used the terms of liberali and servili (emulating the Spanish word serviles applied to supporters of absolutism), and in the end talked of resisting by means of a guerrilla. For both Portuguese and Italian liberals of these years, the Spanish constitution of 1812 remained the standard document of reference.

^ Articles 18–26 of the Constitution. Spain, The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2003.

^ Rodríguez, The Independence of Spanish America, 80–81.

^ Chust, Manuel (1999). La cuestión nacional americana en las Cortes de Cádiz. Valencia: Fundación Instituto de Historia Social UNED. pp. 43–45.

^ Chust, Manuel (1999). La cuestión nacional americana en las Cortes de Cádiz. Valencia: Fundación Instituto de Historia Social UNED. p. 55. Rodríguez, 82–86.

^ Peña, Lorenzo (2002). Un puente jurídico entre Iberoamérica y Europa: la Constitución española de 1812 (PDF) (in Spanish). Casa de América-CSIC. pp. 6–7. ISBN 84-88490-55-0.

^ Articles 1, 5 and 10 established the Empire as the territory of Spain and Spaniards as all "freemen born and bred in the Spanish dominions," "foreigners who may have obtained letters of naturalization from the Cortes" or "those [people] who, without [these letters] have resided ten years in any village of Spain, and acquired thereby a right of vicinity" and "slaves who receive their freedom in the Spanish dominions."

^ "La nación española es la reunión de los españoles de ambos hemisferios."

^ Articles 18 through 22.

^ Valentin Paniagua, Los orígenes del gobierno representativo en el Perú: las elecciones (1809–1826), Fondo Editorial PUCP, 2003, 116.

ISBN 9972-42-607-6

^ Articles 22 and 29.

^ Chust, 70–74, 149–157. Rodríguez, 86.

^ Chust, 53–68, 127–150.

^ Alfonso Bullon de Mendoza y Gomez de Valugera, "Revolución y contrarrevolución en España y América (1808–1840)" in Javier Parades Alonso (ed.), España Siglo XIX, ACTAS, 1991.

ISBN 84-87863-03-5, p. 81–82.