Pontiac's War

| Pontiac's War Pontiac's Rebellion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

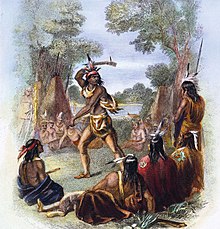

In a famous council on April 28, 1763, Pontiac urged listeners to rise up against the British. (19th century engraving by Alfred Bobbett). | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

Ottawas

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Pontiac | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

~3,000 soldiers[1] | ~3,500 soldiers[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

450 soldiers killed, 2,000 civilians killed or captured, 4,000 civilians displaced | unknown. Civilian casualties unknown. | ||||||||

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of elements of Native American tribes, primarily from the Great Lakes region, the Illinois Country, and Ohio Country who were dissatisfied with British postwar policies in the Great Lakes region after the British victory in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). Warriors from numerous tribes joined the uprising in an effort to drive British soldiers and settlers out of the region. The war is named after the Odawa leader Pontiac, the most prominent of many native leaders in the conflict.

The war began in May 1763 when Native Americans, offended by the policies of British General Jeffrey Amherst, attacked a number of British forts and settlements. Eight forts were destroyed, and hundreds of colonists were killed or captured, with many more fleeing the region. Hostilities came to an end after British Army expeditions in 1764 led to peace negotiations over the next two years. Native Americans were unable to drive away the British, but the uprising prompted the British government to modify the policies that had provoked the conflict.

Warfare on the North American frontier was brutal, and the killing of prisoners, the targeting of civilians, and other atrocities were widespread. The ruthlessness and treachery of the conflict was a reflection of a growing divide between the separate populations of the British colonists and Native Americans. Contrary to popular belief, the British government did not issue the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in reaction to Pontiac's War, though the conflict did provide an impetus for the application of the Proclamation's Indian clauses.[3] This proved unpopular with British colonists, and may have been one of the early contributing factors to the American Revolution.

Contents

1 Naming the conflict

2 Origins

2.1 Tribes involved

2.2 Amherst's policies

2.3 Land and religion

3 Outbreak of war, 1763

3.1 Planning the war

3.2 Siege of Fort Detroit

3.3 Small forts taken

3.4 Siege of Fort Pitt

3.5 Bushy Run and Devil's Hole

4 Paxton Boys

5 British response, 1764–1766

5.1 Fort Niagara treaty

5.2 Two expeditions

5.3 Treaty with Pontiac

6 Legacy

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Naming the conflict

The conflict is named after its most famous participant, the Ottawa leader Pontiac; variations include "Pontiac's War", "Pontiac's Rebellion", and "Pontiac's Uprising". An early name for the war was the "Kiyasuta and Pontiac War", "Kiyasuta" being an alternate spelling for Guyasuta, an influential Seneca/Mingo leader.[4] The war became widely known as "Pontiac's Conspiracy" after the publication in 1851 of Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac.[5] Parkman's influential book, the definitive account of the war for nearly a century, is still in print.[6]

In the 20th century, some historians argued that Parkman exaggerated the extent of Pontiac's influence in the conflict and that it was misleading to name the war after Pontiac. For example, in 1988 Francis Jennings wrote: "In Francis Parkman's murky mind the backwoods plots emanated from one savage genius, the Ottawa chief Pontiac, and thus they became 'The Conspiracy of Pontiac,' but Pontiac was only a local Ottawa war chief in a 'resistance' involving many tribes."[7] Alternate titles for the war have been proposed, but historians generally continue to refer to the war by the familiar names, with "Pontiac's War" probably the most commonly used. "Pontiac's Conspiracy" is now infrequently used by scholars.[8]

Origins

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

Nimwha, Shawnee diplomat, to George Croghan, 1768[9]

In the decades before Pontiac's Rebellion, France and Great Britain participated in a series of wars in Europe that also involved the French and Indian Wars in North America. The largest of these wars was the worldwide Seven Years' War, in which France lost New France in North America to Great Britain. Peace with the Shawnee and Lenape who had been combatants came in 1758 with the Treaty of Easton, where the British promised not to settle further beyond the ridge of the Alleghenies – a demarcation later to be confirmed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, though it was little respected. Most fighting in the North American theater of the war, generally referred to as the French and Indian War in the United States, came to an end after British General Jeffrey Amherst captured Montreal, the last important French settlement, in 1760.[10]

British troops proceeded to occupy the various forts in the Ohio Country and Great Lakes region previously garrisoned by the French. Even before the war officially ended with the Treaty of Paris (1763), the British Crown began to implement changes in order to administer its vastly expanded North American territory. While the French had long cultivated alliances among certain of the Native Americans, the British post-war approach was essentially to treat the Native Americans as a conquered people.[11] Before long, Native Americans who had been allies of the defeated French found themselves increasingly dissatisfied with the British occupation and the new policies imposed by the victors.

Tribes involved

Native Americans involved in Pontiac's Rebellion lived in a vaguely defined region of New France known as the pays d'en haut ("the upper country"), which was claimed by France until the Paris peace treaty of 1763. Native Americans of the pays d'en haut were from many different tribes. At this time and place, a "tribe" was a linguistic or familial group rather than a political unit. No chief spoke for an entire tribe, and no tribe acted in unison. For example, Ottawas did not go to war as a tribe: some Ottawa leaders chose to do so, while other Ottawa leaders denounced the war and stayed clear of the conflict.[12]

The tribes of the pays d'en haut consisted of three basic groups. The first group was composed of tribes of the Great Lakes region: Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi, who spoke Algonquian languages; and the Huron, who spoke an Iroquoian language. They had long been allied with French habitants, with whom they lived, traded, and intermarried. Great Lakes Native Americans were alarmed to learn that they were under British sovereignty after the French loss of North America. When a British garrison took possession of Fort Detroit from the French in 1760, local Native Americans cautioned them that "this country was given by God to the Indians."[13]

The main area of action in Pontiac's Rebellion

The second group was made up of the tribes from eastern Illinois Country, which included the Miami, Wea, Kickapoo, Mascouten, and Piankashaw.[14] Like the Great Lakes tribes, these people had a long history of close trading and other relations with the French. Throughout the war, the British were unable to project military power into the Illinois Country, which was on the remote western edge of the conflict. The Illinois tribes were the last to come to terms with the British.[15]

The third group was made up of tribes of the Ohio Country: Delawares (Lenape), Shawnee, Wyandot, and Mingo. These people had migrated to the Ohio valley earlier in the century from the mid-Atlantic and other eastern areas in order to escape British, French, and Iroquois domination in the New York and Pennsylvania area.[16] Unlike the Great Lakes and Illinois Country tribes, Ohio Native Americans had no great attachment to the French regime. They had fought as French allies in the previous war in an effort to drive away the British.[17] They made a separate peace with the British with the understanding that the British Army would withdraw from the Ohio Country. But after the departure of the French, the British strengthened their forts in the region rather than abandoning them, and so the Ohioans went to war in 1763 in another attempt to drive out the British.[18]

Outside the pays d'en haut, most warriors of the influential Iroquois Confederacy did not participate in Pontiac's War because of their alliance with the British, known as the Covenant Chain. However, the westernmost Iroquois nation, the Seneca tribe, had become disaffected with the alliance. As early as 1761, the Seneca began to send out war messages to the Great Lakes and Ohio Country tribes, urging them to unite in an attempt to drive out the British. When the war finally came in 1763, many Seneca were quick to take action.[19][20]

Amherst's policies

The policies of General Jeffrey Amherst, a British hero of the Seven Years' War, helped to provoke another war. Oil painting by Joshua Reynolds, 1765.

General Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America, was in overall charge of administering policy towards Native Americans, which involved both military matters and regulation of the fur trade. Amherst believed that with France out of the picture, the Native Americans would have no other choice than to accept British rule. He also believed that they were incapable of offering any serious resistance to the British Army; therefore, of the 8,000 troops under his command in North America, only about 500 were stationed in the region where the war erupted.[21] Amherst and officers such as Major Henry Gladwin, commander at Fort Detroit, made little effort to conceal their contempt for the Native Americans. Native Americans involved in the uprising frequently complained that the British treated them no better than slaves or dogs.[22]

Additional Native resentment resulted from Amherst's decision in February 1761 to cut back on the gifts given to the Native Americans. Gift giving had been an integral part of the relationship between the French and the tribes of the pays d'en haut. Following a Native American custom that carried important symbolic meaning, the French gave presents (such as guns, knives, tobacco, and clothing) to village chiefs, who in turn redistributed these gifts to their people. By this process, the village chiefs gained stature among their people, and were thus able to maintain the alliance with the French.[23] Amherst, however, considered this process to be a form of bribery that was no longer necessary, especially since he was under pressure to cut expenses after the war with France. Many Native Americans regarded this change in policy as an insult and an indication that the British looked upon them as conquered people rather than as allies.[24] Since gifts were considered necessary to diplomacy and peaceful co-existence, this change in policy led to a breakdown in any future talks.[25]

Amherst also began to restrict the amount of ammunition and gunpowder that traders could sell to Native Americans. While the French had always made these supplies available, Amherst did not trust the Native Americans, particularly after the "Cherokee Rebellion" of 1761, in which Cherokee warriors took up arms against their former British allies. As the Cherokee war effort had collapsed because of a shortage of gunpowder, so Amherst hoped that future uprisings could be prevented by restricting gunpowder. This created resentment and hardship because gunpowder and ammunition were wanted by native men because it helped them to provide game for their families and skins for the fur trade. Many Native Americans began to believe that the British were disarming them as a prelude to making war upon them. Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of the Indian Department, tried to warn Amherst of the dangers of cutting back on gifts and gunpowder, but to no avail.[26]

Land and religion

Land was also an issue in the coming of the war. While the French colonists—most of whom were farmers who seasonally engaged in fur trade—had always been relatively few, there seemed to be no end of settlers in the British colonies, who wanted to clear the land of trees and occupy it. Shawnees and Delawares in the Ohio Country had been displaced by British colonists in the east, and this motivated their involvement in the war. On the other hand, Native Americans in the Great Lakes region and the Illinois Country had not been greatly affected by white settlement, although they were aware of the experiences of tribes in the east. Historian Gregory Dowd argues that most Native Americans involved in Pontiac's Rebellion were not immediately threatened with displacement by white settlers, and that historians have therefore overemphasized British colonial expansion as a cause of the war. Dowd believes that the presence, attitude, and policies of the British Army, which the Native Americans found threatening and insulting, were more important factors.[27]

Also contributing to the outbreak of war was a religious awakening which swept through Native settlements in the early 1760s. The movement was fed by discontent with the British as well as food shortages and epidemic disease. The most influential individual in this phenomenon was Neolin, known as the "Delaware Prophet", who called upon Native Americans to shun the trade goods, alcohol, and weapons of the whites. Merging elements from Christianity into traditional religious beliefs, Neolin told listeners that the Master of Life was displeased with the Native Americans for taking up the bad habits of the white men, and that the British posed a threat to their very existence. "If you suffer the English among you," said Neolin, "you are dead men. Sickness, smallpox, and their poison [alcohol] will destroy you entirely."[28] It was a powerful message for a people whose world was being changed by forces that seemed beyond their control.[29]

Outbreak of war, 1763

Planning the war

Pontiac takes up the war hatchet.

Although fighting in Pontiac's Rebellion began in 1763, rumors reached British officials as early as 1761 that discontented Native Americans were planning an attack. Senecas of the Ohio Country (Mingos) circulated messages ("war belts" made of wampum) which called for the tribes to form a confederacy and drive away the British. The Mingos, led by Guyasuta and Tahaiadoris, were concerned about being surrounded by British forts.[30] Similar war belts originated from Detroit and the Illinois Country.[31] The Native Americans were not unified, however, and in June 1761, Native Americans at Detroit informed the British commander of the Seneca plot.[32] After William Johnson held a large council with the tribes at Detroit in September 1761 a tenuous peace was maintained, but war belts continued to circulate.[33] Violence finally erupted after the Native Americans learned in early 1763 of the imminent French cession of the pays d'en haut to the British.[34]

Pontiac has often been imagined by artists, as in this 19th-century painting by John Mix Stanley, but no contemporary portraits are known to exist.[35]

The war began at Fort Detroit under the leadership of Pontiac, and quickly spread throughout the region. Eight British forts were taken; others, including Fort Detroit and Fort Pitt, were unsuccessfully besieged. Francis Parkman's The Conspiracy of Pontiac portrayed these attacks as a coordinated operation planned by Pontiac.[36] Parkman's interpretation remains well known, but other historians have since argued that there is no clear evidence that the attacks were part of a master plan or overall "conspiracy".[37] The prevailing view among scholars today is that, rather than being planned in advance, the uprising spread as word of Pontiac's actions at Detroit traveled throughout the pays d'en haut, inspiring already discontented Native Americans to join the revolt. The attacks on British forts were not simultaneous: most Ohio Native Americans did not enter the war until nearly a month after the beginning of Pontiac's siege at Detroit.[38]

Parkman also believed that Pontiac's War had been secretly instigated by French colonists who were stirring up the Native Americans in order to make trouble for the British. This belief was widely held by British officials at the time, but subsequent historians have found no evidence of official French involvement in the uprising. (The rumor of French instigation arose in part because French war belts from the Seven Years' War were still in circulation in some Native villages.) Rather than the French stirring up the Native Americans, some historians now argue that the Native Americans were trying to stir up the French. Pontiac and other native leaders frequently spoke of the imminent return of French power and the revival of the Franco-Native alliance; Pontiac even flew a French flag in his village. All of this was apparently intended to inspire the French to rejoin the struggle against the British. Although some French colonists and traders supported the uprising, the war was initiated and conducted by Native Americans who had Native—not French—objectives.[39]

Historian Richard Middleton (2007) argues that Pontiac's vision, courage, persistence, and organizational abilities allowed him to activate a remarkable coalition of Indian nations prepared to fight successfully against the British. Though the idea to gain independence for all Native Americans west of the Allegheny Mountains did not originate with him but with two Seneca leaders, Tahaiadoris and Guyasuta, by February 1763 Pontiac appeared to embrace the idea. At an emergency council meeting, Pontiac clarified his military support of the broad Seneca plan and worked to galvanize other nations into the military operation that he helped lead, in direct contradiction to traditional Indian leadership and tribal structure. He achieved this coordination through the distribution of war belts: first to the northern Ojibwa and Ottawa near Michilimackinac; and then after the failure to seize Detroit by stratagem, to the Mingo (Seneca) on the upper Allegheny River, the Ohio Delaware near Fort Pitt, and the more westerly Miami, Kickapoo, Piankashaw and Wea peoples.[40]

Siege of Fort Detroit

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council on the banks of the Ecorse River, in what is now Lincoln Park, Michigan, about 10 miles (15 km) southwest of Detroit. Using the teachings of Neolin to inspire his listeners, Pontiac convinced a number of Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons to join him in an attempt to seize Fort Detroit.[41] On May 1, Pontiac visited the fort with 50 Ottawas in order to assess the strength of the garrison.[42] According to a French chronicler, in a second council Pontiac proclaimed:

It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have done from our brothers, the French.... Therefore, my brothers, we must all swear their destruction and wait no longer. Nothing prevents us; they are few in numbers, and we can accomplish it.[43]

Hoping to take the stronghold by surprise, on May 7 Pontiac entered Fort Detroit with about 300 men carrying concealed weapons. The British had learned of Pontiac's plan, however, and were armed and ready.[44] His tactic foiled, Pontiac withdrew after a brief council and, two days later, laid siege to the fort. Pontiac and his allies killed all of the British soldiers and settlers they could find outside of the fort, including women and children.[45] One of the soldiers was ritually cannibalized, as was the custom in some Great Lakes Native cultures.[46] The violence was directed at the British; French colonists were generally left alone. Eventually more than 900 soldiers from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege. Meanwhile, on May 28 a British supply column from Fort Niagara led by Lieutenant Abraham Cuyler was ambushed and defeated at Point Pelee.[47]

After receiving reinforcements, the British attempted to make a surprise attack on Pontiac's encampment. But Pontiac was ready and waiting, and defeated them at the Battle of Bloody Run on July 31, 1763. Nevertheless, the situation at Fort Detroit remained a stalemate, and Pontiac's influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Native Americans began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing. On October 31, 1763, finally convinced that the French in Illinois would not come to his aid at Detroit, Pontiac lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River, where he continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.[48]

Small forts taken

Forts and battles of Pontiac's War

Before other British outposts had learned about Pontiac's siege at Detroit, Native Americans captured five small forts in a series of attacks between May 16 and June 2.[49] The first to be taken was Fort Sandusky, a small blockhouse on the shore of Lake Erie. It had been built in 1761 by order of General Amherst, despite the objections of local Wyandots, who in 1762 warned the commander that they would soon burn it down.[50] On May 16, 1763, a group of Wyandots gained entry under the pretense of holding a council, the same stratagem that had failed in Detroit nine days earlier. They seized the commander and killed the other 15 soldiers, as well as British traders at the fort.[51] These were among the first of about 100 traders who were killed in the early stages of the war.[49] The dead were ritually scalped and the fort—as the Wyandots had warned a year earlier—was burned to the ground.[52]

Fort St. Joseph (the site of present-day Niles, Michigan) was captured on May 25, 1763, by the same method as at Sandusky. Potawatomis seized the commander and killed most of the 15-man garrison outright.[53]Fort Miami (on the site of present Fort Wayne, Indiana) was the third fort to fall. On May 27, 1763, the commander was lured out of the fort by his Native mistress and shot dead by Miami Native Americans. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.[54]

In the Illinois Country, Weas, Kickapoos, and Mascoutens took Fort Ouiatenon (about 5 miles (8.0 km) west of present Lafayette, Indiana) on June 1, 1763. They lured soldiers outside for a council, and took the 20-man garrison captive without bloodshed. The Native Americans around Fort Ouiatenon had good relations with the British garrison, but emissaries from Pontiac at Detroit had convinced them to strike. The warriors apologized to the commander for taking the fort, saying that "they were obliged to do it by the other Nations."[55] In contrast with other forts, the Natives did not kill the British captives at Ouiatenon.[56]

The fifth fort to fall, Fort Michilimackinac (present Mackinaw City, Michigan), was the largest fort taken by surprise. On June 2, 1763, local Ojibwas staged a game of stickball (a forerunner of lacrosse) with visiting Sauks. The soldiers watched the game, as they had done on previous occasions. The ball was hit through the open gate of the fort; the teams rushed in and were given weapons which Native women had smuggled into the fort. The warriors killed about 15 of the 35-man garrison in the struggle; later they killed five more in ritual torture.[57]

Three forts in the Ohio Country were taken in a second wave of attacks in mid-June. Iroquois Senecas took Fort Venango (near the site of the present Franklin, Pennsylvania) around June 16, 1763. They killed the entire 12-man garrison outright, keeping the commander alive to write down the grievances of the Senecas. After that, they ritually burned him at the stake.[58] Possibly the same Seneca warriors attacked Fort Le Boeuf (on the site of Waterford, Pennsylvania) on June 18, but most of the 12-man garrison escaped to Fort Pitt.[59]

On June 19, 1763, about 250 Ottawa, Ojibwa, Wyandot, and Seneca warriors surrounded Fort Presque Isle (on the site of Erie, Pennsylvania), the eighth and final fort to fall. After holding out for two days, the garrison of about 30 to 60 men surrendered, on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt.[60] The warriors killed most of the soldiers after they came out of the fort.[61]

Siege of Fort Pitt

Colonists in western Pennsylvania fled to the safety of Fort Pitt after the outbreak of the war. Nearly 550 people crowded inside, including more than 200 women and children.[62] Simeon Ecuyer, the Swiss-born British officer in command, wrote that "We are so crowded in the fort that I fear disease...; the smallpox is among us."[63] Fort Pitt was attacked on June 22, 1763, primarily by Delawares. Too strong to be taken by force, the fort was kept under siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee war parties raided deep into Pennsylvania, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of settlers in scattered farms. Two smaller strongholds that linked Fort Pitt to the east, Fort Bedford and Fort Ligonier, were sporadically fired upon throughout the conflict, but were never taken.[64]

Before the war, Amherst had dismissed the possibility that the Native Americans would offer any effective resistance to British rule, but that summer he found the military situation becoming increasingly grim. He ordered subordinates to "immediately ... put to death" captured enemy Native American warriors. To Colonel Henry Bouquet at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who was preparing to lead an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt, Amherst wrote on about June 29, 1763: "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them."[65] Bouquet responded to Amherst (summer of 1763):[66]

P.S. I will try to inocculate [sic] the Indians by means of Blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself. As it is pity to oppose good men against them, I wish we could make use of the Spaniard's Method, and hunt them with English Dogs. Supported by Rangers, and some Light Horse, who would I think effectively extirpate or remove that Vermine.

In a postscript, Amherst replied:[66]

P.S. You will Do well to try to Innoculate [sic] the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race. I should be very glad your Scheme for Hunting them Down by Dogs could take Effect, but England is at too great a Distance to think of that at present.

Officers at the besieged Fort Pitt had already attempted to do what Amherst and Bouquet were discussing, apparently on their own initiative. During a parley at Fort Pitt on June 24, 1763, Ecuyer gave Delaware representatives, Turtleheart and Mamaltee,[67] two blankets and a handkerchief that had been exposed to smallpox, hoping to spread the disease to the Native Americans in order to "extirpate" them from the territory.[68]William Trent, the militia commander, left records that showed the purpose of giving the blankets was "to Convey the Smallpox to the Indians."[69][70]Turtleheart and Killbuck would later represent the Delaware at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768.[71]

On July 22, Trent writes, "Gray Eyes, Wingenum, Turtle's Heart and Mamaultee, came over the River told us their Chiefs were in Council, that they waited for Custaluga who they expected that Day".[72] There are eyewitness reports[73][74] that outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases had plagued the Ohio Native Americans in the years prior to the siege of Fort Pitt.[75] Colonists also caught smallpox from Native Americans at a peace conference in 1759 which then led to an epidemic in Charleston and the surrounding areas in South Carolina.[72]

Historians are at odds as to how much damage the attempt to spread smallpox at Fort Pitt caused. Historian Francis Jennings concluded that the attempt was "unquestionably successful and effective" and inflicted great damage to the Native Americans.[76] Historian Michael McConnell writes that, "Ironically, British efforts to use pestilence as a weapon may not have been either necessary or particularly effective", noting that smallpox was already entering the territory by several means, and Native Americans were familiar with the disease and adept at isolating the infected.[77] Historians widely agree that smallpox devastated the Native American population.[78][79]

Bushy Run and Devil's Hole

On August 1, 1763, most of the Native Americans broke off the siege at Fort Pitt in order to intercept 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at the Battle of Bushy Run. Although his force suffered heavy casualties, Bouquet fought off the attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20, bringing the siege to an end. His victory at Bushy Run was celebrated in the British colonies—church bells rang through the night in Philadelphia—and praised by King George.[80]

This victory was soon followed by a costly defeat. Fort Niagara, one of the most important western forts, was not assaulted, but on September 14, 1763, at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls portage. Two companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. More than 70 soldiers and teamsters were killed in these actions, which Anglo-Americans called the "Devil's Hole Massacre", the deadliest engagement for British soldiers during the war.[81]

Paxton Boys

Massacre of the Indians at Lancaster by the Paxton Boys in 1763, lithograph published in Events in Indian History (John Wimer, 1841).

The violence and terror of Pontiac's War convinced many western Pennsylvanians that their government was not doing enough to protect them. This discontent was manifested most seriously in an uprising led by a vigilante group that came to be known as the Paxton Boys, so-called because they were primarily from the area around the Pennsylvania village of Paxton (or Paxtang). The Paxtonians turned their anger towards Native Americans—many of them Christians—who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements. Prompted by rumors that a Native war party had been seen at the Native village of Conestoga, on December 14, 1763, a group of more than 50 Paxton Boys marched on the village and murdered the six Susquehannocks they found there. Pennsylvania officials placed the remaining 16 Susquehannocks in protective custody in Lancaster, but on December 27 the Paxton Boys broke into the jail and slaughtered most of them. Governor John Penn issued bounties for the arrest of the murderers, but no one came forward to identify them.[82]

The Paxton Boys then set their sights on other Native Americans living within eastern Pennsylvania, many of whom fled to Philadelphia for protection. Several hundred Paxtonians marched on Philadelphia in January 1764, where the presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia prevented them from committing more violence. Benjamin Franklin, who had helped organize the local militia, negotiated with the Paxton leaders and brought an end to the immediate crisis. Franklin published a scathing indictment of the Paxton Boys. "If an Indian injures me," he asked, "does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?"[83] One leader of the Paxton Boys was Lazarus Stewart who would be killed in the Wyoming Massacre of 1778.

British response, 1764–1766

Native American raids on frontier settlements escalated in the spring and summer of 1764. The hardest hit colony that year was Virginia, where more raids occurred on July 26, when four Delaware Indian soldiers killed and scalped a school teacher and ten children in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania. Incidents such as these prompted the Pennsylvania Assembly, with the approval of Governor Penn, to reintroduce the scalp bounties offered during the French and Indian War, which paid money for every Native killed above the age of ten, including women.[84]

General Amherst, held responsible for the uprising by the Board of Trade, was recalled to London in August 1763 and replaced by Major General Thomas Gage. In 1764, Gage sent two expeditions into the west to crush the rebellion, rescue British prisoners, and arrest the Native Americans responsible for the war. According to historian Fred Anderson, Gage's campaign, which had been designed by Amherst, prolonged the war for more than a year because it focused on punishing the Native Americans rather than ending the war. Gage's one significant departure from Amherst's plan was to allow William Johnson to conduct a peace treaty at Niagara, giving those Native Americans who were ready to "bury the hatchet" a chance to do so.[85]

Fort Niagara treaty

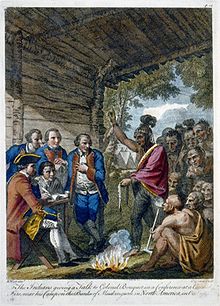

Bouquet's negotiations are depicted in this 1765 engraving based on a painting by Benjamin West. The Native orator holds a belt of wampum, essential for diplomacy in the Eastern Woodlands.

From July to August 1764, Johnson negotiated a treaty at Fort Niagara with about 2,000 Native Americans in attendance, primarily Iroquois. Although most Iroquois had stayed out of the war, Senecas from the Genesee River valley had taken up arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the Covenant Chain alliance. As restitution for the Devil's Hole ambush, the Senecas were compelled to cede the strategically important Niagara portage to the British. Johnson even convinced the Iroquois to send a war party against the Ohio Native Americans. This Iroquois expedition captured a number of Delawares and destroyed abandoned Delaware and Shawnee towns in the Susquehanna Valley, but otherwise the Iroquois did not contribute to the war effort as much as Johnson had desired.[86]

Two expeditions

Having secured the area around Fort Niagara, the British launched two military expeditions into the west. The first expedition, led by Colonel John Bradstreet, was to travel by boat across Lake Erie and reinforce Detroit. Bradstreet was to subdue the Native Americans around Detroit before marching south into the Ohio Country. The second expedition, commanded by Colonel Bouquet, was to march west from Fort Pitt and form a second front in the Ohio Country.

Bradstreet set out from Fort Schlosser in early August 1764 with about 1,200 soldiers and a large contingent of Native allies enlisted by Sir William Johnson. Bradstreet felt that he did not have enough troops to subdue enemy Native Americans by force, and so when strong winds on Lake Erie forced him to stop at Presque Isle on August 12, he decided to negotiate a treaty with a delegation of Ohio Native Americans led by Guyasuta. Bradstreet exceeded his authority by conducting a peace treaty rather than a simple truce, and by agreeing to halt Bouquet's expedition, which had not yet left Fort Pitt. Gage, Johnson, and Bouquet were outraged when they learned what Bradstreet had done. Gage rejected the treaty, believing that Bradstreet had been duped into abandoning his offensive in the Ohio Country. Gage may have been correct: the Ohio Native Americans did not return prisoners as promised in a second meeting with Bradstreet in September, and some Shawnees were trying to enlist French aid in order to continue the war.[87]

Bradstreet continued westward, as yet unaware that his unauthorized diplomacy was angering his superiors. He reached Fort Detroit on August 26, where he negotiated another treaty. In an attempt to discredit Pontiac, who was not present, Bradstreet chopped up a peace belt the Ottawa leader had sent to the meeting. According to historian Richard White, "such an act, roughly equivalent to a European ambassador's urinating on a proposed treaty, had shocked and offended the gathered Indians." Bradstreet also claimed that the Native Americans had accepted British sovereignty as a result of his negotiations, but Johnson believed that this had not been fully explained to the Native Americans and that further councils would be needed. Although Bradstreet had successfully reinforced and reoccupied British forts in the region, his diplomacy proved to be controversial and inconclusive.[88]

Colonel Bouquet, delayed in Pennsylvania while mustering the militia, finally set out from Fort Pitt on October 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. He marched to the Muskingum River in the Ohio Country, within striking distance of a number of native villages. Now that treaties had been negotiated at Fort Niagara and Fort Detroit, the Ohio Native Americans were isolated and, with some exceptions, ready to make peace. In a council which began on October 17, Bouquet demanded that the Ohio Native Americans return all captives, including those not yet returned from the French and Indian War. Guyasuta and other leaders reluctantly handed over more than 200 captives, many of whom had been adopted into Native families. Because not all of the captives were present, the Native Americans were compelled to surrender hostages as a guarantee that the other captives would be returned. The Ohio Native Americans agreed to attend a more formal peace conference with William Johnson, which was finalized in July 1765.[89]

Treaty with Pontiac

Although the military conflict essentially ended with the 1764 expeditions,[90] Native Americans still called for resistance in the Illinois Country, where British troops had yet to take possession of Fort de Chartres from the French. A Shawnee war chief named Charlot Kaské emerged as the most strident anti-British leader in the region, temporarily surpassing Pontiac in influence. Kaské traveled as far south as New Orleans in an effort to enlist French aid against the British.[91]

In 1765, the British decided that the occupation of the Illinois Country could only be accomplished by diplomatic means. As Gage commented to one of his officers, he was determined to have "none our enemy" among the Indian peoples, and that included Pontiac, to whom he now sent a wampum belt suggesting peace talks. Pontiac had by now become less militant after hearing of Bouquet's truce with the Ohio country Native Americans.[92] Johnson's deputy, George Croghan, accordingly travelled to the Illinois country in the summer of 1765, and although he was injured along the way in an attack by Kickapoos and Mascoutens, he managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac. While Charlot Kaské wanted to burn Croghan at the stake,[93] Pontiac urged moderation and agreed to travel to New York, where he made a formal treaty with William Johnson at Fort Ontario on July 25, 1766. It was hardly a surrender: no lands were ceded, no prisoners returned, and no hostages were taken.[94] Rather than accept British sovereignty, Kaské left British territory by crossing the Mississippi River with other French and Native refugees.[95]

Legacy

Because many children taken as captives had been adopted into Native families, their forced return often resulted in emotional scenes, as depicted in this engraving based on a painting by Benjamin West.

The total loss of life resulting from Pontiac's War is unknown. About 400 British soldiers were killed in action and perhaps 50 were captured and tortured to death.[96] George Croghan estimated that 2,000 settlers had been killed or captured, a figure sometimes repeated as 2,000 settlers killed.[97] The violence compelled approximately 4,000 settlers from Pennsylvania and Virginia to flee their homes.[98] Native American losses went mostly unrecorded.

Pontiac's War has traditionally been portrayed as a defeat for the Native Americans,[99] but scholars now usually view it as a military stalemate: while the Native Americans had failed to drive away the British, the British were unable to conquer the Native Americans. Negotiation and accommodation, rather than success on the battlefield, ultimately brought an end to the war.[100] The Native Americans had in fact won a victory of sorts by compelling the British government to abandon Amherst's policies and instead create a relationship with the Native Americans modeled on the Franco-Native alliance.[101]

Relations between British colonists and Native Americans, which had been severely strained during the French and Indian War, reached a new low during Pontiac's Rebellion.[102] According to historian David Dixon, "Pontiac's War was unprecedented for its awful violence, as both sides seemed intoxicated with genocidal fanaticism."[103] Historian Daniel Richter characterizes the Native attempt to drive out the British, and the effort of the Paxton Boys to eliminate Native Americans from their midst, as parallel examples of ethnic cleansing.[104] People on both sides of the conflict had come to the conclusion that colonists and Native Americans were inherently different and could not live with each other. According to Richter, the war saw the emergence of "the novel idea that all Native people were 'Indians,' that all Euro-Americans were 'Whites,' and that all on one side must unite to destroy the other."[105]

The British government also came to the conclusion that colonists and Native Americans must be kept apart. On October 7, 1763, the Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, an effort to reorganize British North America after the Treaty of Paris. The Proclamation, already in the works when Pontiac's War erupted, was hurriedly issued after news of the uprising reached London. Officials drew a boundary line between the British colonies along the seaboard, and Native American lands west of the Allegheny Ridge (i.e., the Eastern Divide), creating a vast 'Indian Reserve' that stretched from the Alleghenies to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Quebec. It thus confirmed the antebellum demarcation that had been set by the Treaty of Easton in 1758. By forbidding colonists from trespassing on Native lands, the British government hoped to avoid more conflicts like Pontiac's Rebellion. "The Royal Proclamation," writes historian Colin Calloway, "reflected the notion that segregation not interaction should characterize Indian-white relations."[106]

The effects of Pontiac's War were long-lasting. Because the Proclamation officially recognized that indigenous people had certain rights to the lands they occupied, it has been called the Native Americans' "Bill of Rights", and still informs the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations.[107] For British colonists and land speculators, however, the Proclamation seemed to deny them the fruits of victory—western lands—that had been won in the war with France. The resentment which this created undermined colonial attachment to the Empire, contributing to the coming of the American Revolution.[108] According to Colin Calloway, "Pontiac's Revolt was not the last American war for independence—American colonists launched a rather more successful effort a dozen years later, prompted in part by the measures the British government took to try to prevent another war like Pontiac's."[109]

For Native Americans, Pontiac's War demonstrated the possibilities of pan-tribal cooperation in resisting Anglo-American colonial expansion. Although the conflict divided tribes and villages,[110] the war also saw the first extensive multi-tribal resistance to European colonization in North America, and was the first war between Europeans and Native North Americans that did not end in complete defeat for the Native Americans.[111] The Proclamation of 1763 ultimately did not prevent British colonists and land speculators from expanding westward, and so Native Americans found it necessary to form new resistance movements. Beginning with conferences hosted by Shawnees in 1767, in the following decades leaders such as Joseph Brant, Alexander McGillivray, Blue Jacket, and Tecumseh would attempt to forge confederacies that would revive the resistance efforts of Pontiac's War.[112]

See also

- Colonial American military history

- Council Point Park

- List of Indian massacres

Pontiac's Rebellion school massacre of 1764

Notes

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 117; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 158.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 117.

^ Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant, 67; Ray, I Have Lived Here, 127; Stagg, Anglo-Indian Relations, 334-37.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 303n21; Peckham, Pontiac and the Indian Uprising, 107n.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", x.

^ McConnell, "Introduction", xiii; Dowd, War under Heaven, 7.

^ Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 442.

^ Alternative titles include "Western Indians' Defensive War" (used by McConnell, A Country Between, after historian W. J. Eccles) and "The Amerindian War of 1763" (used by Steele, Warpaths). "Pontiac's War" is the term most used by scholars listed in the references. "Pontiac's Conspiracy" remains the Library of Congress subject heading. The case for using the title "Pontiac's War" is made in Richard Middleton's "Pontiac: Local Warrior or Pan Indian Leader?" Michigan Historical Review, vol. 32 (2006), 1–32

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 216.

^ Anderson, Crucible of War, 453.

^ White, Middle Ground, 256.

^ For tribes not political units, see White, Middle Ground, xiv. For other Ottawas denounce war, see White, Middle Ground, 287.

^ White, Middle Ground, 260.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 168.

^ Anderson, Crucible of War, 626–32.

^ McConnell, Country Between, ch. 1.

^ White, Middle Ground, 240–45.

^ White, Middle Ground, 248–55.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 85–89

^ Richard Middleton; Pontiac's War: Its Causes, Course and Consequences; (2007); Pgs. 96–99

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 157–58.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 63–69.

^ White, Middle Ground, 36, 113, 179–83.

^ White, Middle Ground, 256–58; McConnell, A Country Between, 163–64; Dowd, War under Heaven, 70–75.

^ Borrows, John (1997). "Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self Government". In Asch, Michael. Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference (PDF). Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 170..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ For effect of the Cherokee gunpowder shortage on Amherst, see Anderson, Crucible of War, 468–71; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 78. For Native resentment of gunpowder restrictions, see Dowd, War under Heaven, 76–77; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 83.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 82–83.

^ Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 34.

^ White, Middle Ground, 279–85.

^ White, Middle Ground, 272; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 85–87; Middleton, Pontiac's War, 33–46

^ White, Middle Ground, 276.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 105; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 87–88.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 92–93, 100; Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 46–47.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 104.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 6.

^ Parkman, Conspiracy, 1:186–87; McConnell, A Country Between, 182.

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 108–10. Historian Wilbur Jacobs supported Parkman's thesis that Pontiac planned the war in advance, but objected to the use of the word "conspiracy" because it suggested that the Native grievances were unjustified; Jacobs, "Pontiac's War", 83–90.

^ McConnell, A Country Between, 182.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 105–13, 160 (for French flag), 268; White, Middle Ground, 276–77; Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 126. Peckham, like Parkman, argued that the Native Americans took up arms due to the "whispered assurances of the French" (p. 105), although both admitted that the evidence was sketchy.

^ Richard Middleton, Pontiac's War, 68–73

^ Parkman, Conspiracy, 1:200–08.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 108; Peckham, Indian Uprising, 116.

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 119–20; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 109.

^ Because Major Gladwin, the British commander at Detroit, did not reveal the identity of the informant(s) who warned him of Pontiac's plan, historians have named several possible candidates; Dixon, "Never Come to Peace, 109–10; Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 77–8.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 111–12.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 114.

^ Peckham, Indian uprising, 156.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 139.

^ ab Dowd, War under Heaven, 125.

^ McConnell, A Country Between, 167; Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 44.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 86, gives the number of traders killed at Sandusky as 12; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, mentions "three or four", while Dowd, War under Heaven, 125, says that it was "a great many".

^ Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 86; Parkman, Conspiracy, 1:271.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 88–9.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 90.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 121.

^ Nester, Haughty Conquerors", 90–1.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 122; Dowd, War under Heaven, 126; Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 95–97.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 99.

^ Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 101–02.

^ Dixon (Never Come to Peace, 149) says that Presque Isle held 29 soldiers and several civilians, while Dowd (War under Heaven, 127) writes that there were "perhaps sixty men" inside.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 128.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 151; Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 92.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 151.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 130; Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", Pg. 130

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 226; Anderson, Crucible of War, 542, 809n.

^ ab "Amherst and Smallpox". Umass.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

^ Ecuyer, Simeon: Bouquet Papers: Fort Pitt and Letters From the Frontier, 93-93

^ Anderson, Crucible of War, 541–42; Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 447n26.; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 153.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Penn, 73.

^ Trent, William, Journal of William Trent, 1763 from Pen Pictures of Early Western Pennsylvania, John W. Harpster, ed Archived April 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.. (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1938), pp. 99, 103–4.

^ "Proceedings of Sir William Johnson with the Indians at Fort Stanwix to settle a Boundary Line". Earlytreaties.unl.edu. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

^ ab Ranlet, Philip. "The British, the Indians, and smallpox: what actually happened at Fort Pitt in 1763?" Pennsylvania history (2000): 427–441.

^ Hanna, Charles A.: The wilderness trail : or, the ventures and adventures of the Pennsylvania traders on the Allegheny path, with some new annals of the old West, and the Records of some Strong Men and some Bad Ones(1911) 366–367

^ Burke, James P.: Pioneers of Second Fork, 19–22

^ McConnell, A Country Between, 195; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 154.

^ Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 447–48.

^ McConnell, A County Between, 195–96.

^ For an overview of the evidence and historical interpretations, see Elizabeth A. Fenn, "Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst", The Journal of American History, vol. 86, no. 4 (March 2000), 1552–80.

^ Phillip M. White (June 2, 2011). American Indian Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 44, 49.

^ For celebration and praise, see Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 196.

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 224–25; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 210–11; Dowd, War under Heaven, 137.

^ Nester, Haughty Conquerors, 173.

^ Franklin quoted in Nester, Haughty Conquerors, 176.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 222–24; Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", 194.

^ Anderson, Crucible of War, 553, 617–20.

^ For Niagara treaty, see McConnell, A Country Between, 197–99; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 219–20, 228; Dowd, War under Heaven, 151–53.

^ For Bradstreet along Lake Erie, see White, Middle Ground, 291–92; McConnell, A Country Between, 199–200; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 228–29; Dowd, War under Heaven, 155–58. Dowd writes that Bradstreet's Native escort numbered "some six hundred" (p. 155), while Dixon gives it as "more than 250" (p. 228).

^ For Bradstreet at Detroit, see White, Middle Ground, 297–98; McConnell, A Country Between, 199–200; Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 227–32; Dowd, War under Heaven, 153–62.

^ For Bouquet expedition, see Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 233–41; McConnell, A Country Between, 201–05; Dowd, War under Heaven, 162–65.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 242.

^ White, Middle Ground, 300–1; Dowd, War under Heaven, 217–19; Middleton, Pontiac's War, 183-99

^ Middleton, Pontiac's War, 189; White, Middle Ground, 302

^ White, Middle Ground, 305, note 70.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 253–54.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 76, 150.

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 239. Nester ("Haughty Conquerors", 280) lists 500 killed, an apparent misprint since his source is Peckham.

^ For works which report 2,000 killed (rather than killed and captured), see Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 446; Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", vii, 172. Nester later (p. 279) revises this number down to about 450 killed. Dowd argues that Croghan's widely reported estimate "cannot be taken seriously" because it was a "wild guess" made while Croghan was far away in London; Dowd, War under Heaven, 142.

^ Dowd, War under Heaven, 275.

^ Peckham, Indian Uprising, 322.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 242–43; White, Middle Ground, 289; McConnell, "Introduction", xv.

^ White, Middle Ground, 305–09; Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 76; Richter, Facing East, 210.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 77.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, xiii.

^ Richter, Facing East, 190–91.

^ Richter, Facing East, 208.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 92.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 96–98.

^ Dixon, Never Come to Peace, 246.

^ Calloway, Scratch of a Pen, 91.

^ Hinderaker, Elusive Empires, 156.

^ For first extensive war, see Steele, Warpaths, 234. For first war not to be complete Native defeat, see Steele, Warpaths, 247.

^ Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 42–43, 91–93; Dowd, War under Heaven, 264–66.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000.

ISBN 0-375-40642-5. (discussion) - Calloway, Colin. The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America. Oxford University Press, 2006.

ISBN 0-19-530071-8. - Dixon, David. Never Come to Peace Again: Pontiac's Uprising and the Fate of the British Empire in North America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005.

ISBN 0-8061-3656-1. - Dowd, Gregory Evans. A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

ISBN 0-8018-4609-9. - Dowd, Gregory Evans. War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, & the British Empire. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

ISBN 0-8018-7079-8,

ISBN 0-8018-7892-6 (paperback). (review) - Grenier, John. The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

ISBN 0-521-84566-1. - Hinderaker, Eric. Elusive Empires: Constructing Colonialism in the Ohio Valley, 1763–1800. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

ISBN 0-521-66345-8. - Jacobs, Wilbur R. "Pontiac's War—A Conspiracy?" in Dispossessing the American Indian: Indians and Whites on the Colonial Frontier, 83–93. New York: Scribners, 1972.

- Jennings, Francis. Empire of Fortune: Crowns, Colonies, and Tribes in the Seven Years War in America. New York: Norton, 1988.

ISBN 0-393-30640-2. - McConnell, Michael N. A Country Between: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples, 1724–1774. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

ISBN 0-8032-8238-9. (review) - McConnell, Michael N. "Introduction to the Bison Book Edition" of The Conspiracy of Pontiac by Francis Parkman. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

ISBN 0-8032-8733-X. - Middleton, Richard. Pontiac's War: Its Causes, Course, and Consequences (New York, Routledge, 2007).

ISBN 0-415-97913-7

- Middleton, Richard, "Pontiac: Local Warrior or Pan Indian Leader?" Michigan Historical Review, vol. 32 (2006), 1–32

- Miller, J.R.. Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

- Nester, William R. "Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000.

ISBN 0-275-96770-0. A narrative history based mostly on previously published sources, Gregory Dowd writes that "Nester pays little attention to archival sources, sources in French, ethnography, and the past two decades of scholarship on Native American history" (Dowd, War under Heaven, 283n9).

Parkman, Francis. The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada. 2 volumes. Originally published Boston, 1851; revised 1870. Reprinted often, including Bison book edition:

ISBN 0-8032-8733-X (vol 1);

ISBN 0-8032-8737-2 (vol 2). Parkman's landmark work, though still influential, has largely been supplanted by modern scholarship.- Peckham, Howard H. Pontiac and the Indian Uprising. University of Chicago Press, 1947.

ISBN 0-8143-2469-X. - Ray, Arthur J. I Have Lived Here Since the World Began: An Illustrated History of Canada's Native People. Toronto: Key Porter, 1996.

- Richter, Daniel K. Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001.

ISBN 0-674-00638-0. (review) - Stagg, Jack. Anglo-Indian Relations in North-America to 1763 and an Analysis of the Royal Proclamation of 7 October 1763. Ottawa: Indian and Northern Development, 1981.

- Steele, Ian K. Warpaths: Invasions of North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

ISBN 0-19-508223-0. - Ward, Matthew C. "The Microbes of War: The British Army and Epidemic Disease among the Ohio Indians, 1758–1765". In David Curtis Skaggs and Larry L. Nelson, eds., The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814, 63–78. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001.

ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

ISBN 0-521-42460-7. (info)

Further reading

- Auth, Stephen F. The Ten Years' War: Indian-White relations in Pennsylvania, 1755–1765. New York: Garland, 1989.

ISBN 0-8240-6172-1. - Barr, Daniel, ed. The Boundaries between Us: Natives and Newcomers along the Frontiers of the Old Northwest Territory, 1750–1850. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006.

ISBN 0-87338-844-5.

Eckert, Allan W. The Conquerors: A Narrative. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970. Reprinted 2002, Jesse Stuart Foundation,

ISBN 1-931672-06-7,

ISBN 1-931672-07-5 (paperback). Detailed history written in novelized form, generally considered by academic historians to be fiction (see Nester, "Haughty Conquerors", xii; Jennings, Empire of Fortune, 77 n. 13).

Farmer, Silas. (1884) (Jul 1969) The history of Detroit and Michigan, or, The metropolis illustrated: a chronological cyclopaedia of the past and present: including a full record of territorial days in Michigan, and the annuals of Wayne County, in various formats at Open Library.- McConnell, Michael N. Army and Empire: British Soldiers on the American Frontier, 1758–1775. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

- Ward, Matthew C. Breaking the Backcountry: The Seven Years' War in Virginia and Pennsylvania, 1754–1765. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003.

External links

"Sir William Johnson Journal in Detroit 1761", Johnson's account of his prewar diplomatic mission to Detroit, from the Clarke Historical Library at Central Michigan University. Originally published in The Papers of Sir William Johnson (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1962) 13:248–59.