Southern Ndebele people

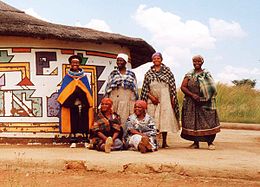

The women of Loopspruit Cultural Village, near Bronkhorstspruit, in front of a traditionally-painted Ndebele dwelling. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1.1 million (2011 Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Limpopo provinces in | |

| Languages | |

| Southern Ndebele language | |

| Religion | |

Christian, Animist | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Nguni peoples (especially Northern Ndebele and Zulu) |

| Southern Ndebele | |

|---|---|

| Person | umNdebele |

| People | amaNdebele |

| Language | isiNdebele seSewula |

The Southern African Ndebele are a Nguni ethnic group native to South Africa who speak Southern Ndebele. Although sharing the same name, they should not be confused with (Mzilikazi's) Northern Ndebele people of modern Zimbabwe, an offshoot of Shaka's Zulu people with whom they came into contact only after Mfecane. Northern Ndebele people speak the Ndebele language.[1] Mzilikazi's Khumalo clan (later called the Ndebele) have a different history (see Zimbabwean Ndebele language) and their language is more similar to Zulu and Xhosa.[2] Southern Ndebele mainly inhabit the provinces of Mpumalanga, Gauteng and Limpopo, all of which are in the northeast of the country.

Contents

1 History

2 Ndebele Kings

2.1 Manala

2.2 Ndzunza

3 Social and cultural life

3.1 Internal political and social structures

4 Personal adornment

5 Arts and craft

6 Special occasions

6.1 Initiation

7 Courtship and marriage

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

History

The Southern Ndebele people’s history has been traced back to King Ndebele, King Ndebele fathered King Langa, King Langa fathered King Mntungwa (not to be confused with the Khumalo Mntungwa, because he was fathered by Mbulazi), King Mntungwa fathered King Jonono, King Jonono fathered King Nanasi, King Nanasi fathered King Mafana, King Mafana fathered King Mhlanga and Chief Libhoko, King Mhlanga fathered King Musi and Chief Skhube.

Ndebele Some of his sons were left behind with the Hlubi tribe

Langa Some of his sons branched and formed the BakaLanga tribe

Mntungwa Founder of the amaNtungwa clan

Njonono He died in Jononoskop near Ladysmith – Surname Jonono is in the Hlubi tribe

Nanasi He died in Jononoskop near Ladysmith – Surname Nanasi is in the Hlubi tribe

Mafana He died in Randfontein (Emhlangeni)

Mhlanga He died in Randfontein (Emhlangeni)

Musi He died in kwaMnyamana (Pretoria)

King Musi’s kraal was based at eMhlangeni a place named after his father Mhlanga, the name of the place is currently known as Randfontein (Mohlakeng) and later moved to KwaMnyamana which is now called Emarula or Bon Accord in Pretoria.

King Musi was a polygamist and fathered the following sons, Skhosana (Masombuka), Manala (Mbuduma), Ndzundza (Hlungwana), Thombeni (Kekana or Gegana), Sibasa, Mhwaduba (Lekhuleni) and Mphafuli and others.

The first born son of king Musi was Skhosana from the third wife, he also was called Masombuka. The name “sombuka” means to begin; hence the first son was called Masombuka. Manala was the first son from the great wife and Ndzundza was the son of the second wife. According to Ndebele custom, the heir to the throne of the king is the first born son from the great wife; hence Manala was the heir to the Ndebele throne.

When the great wife of King Musi died, King Musi was blind through old age and was sickly. He was nursed by his surviving second wife and mother of Ndzundza. Due to the fact that Musi was very old, he was also worried about the Kingship of the Ndebele Nation. Musi did not want Manala to be the King of the Nation hence one day Musi instructed Manala to come and see him in the morning. Musi then instructed Manala to go and hunt for the iMbuduma (Wildebeest) and this was a ploy to keep Manala away from the household in order to hand over the kingship to Ndzundza.

After Manala had left to hunt for the Wildebeest Musi instructed his wife to call her son Ndzundza. King Musi then gave Ndzundza the accessory to the throne, customarily passed on from the incumbent to the successor. Musi knew that if he died naturally then, the kingship will be passed to Manala, hence he passed the kingship to Ndzundza while he was alive, and this was not common at that time for a king to give his son rulership while the king is still alive. This accessory called namrhali was a mysterious object that cries like a child, used to fortify the king.

Musi then instructed Ndzundza to call a Royal meeting (Imbizo) and notify the nation that he is the King and also to live kwaMnyamana with his followers. Many people believed him and a few did not want to follow him. Ndzundza then left with a huge number of people.

When Manala came back from the hunt he realised that Ndzundza had received the namrhali, he then went to see his father. His father informed him that he had already given away the namrhali to Ndzundza. Manala called a Royal meeting (imbizo) with the few people left behind and announced that Ndzundza had stolen the namrhali. Musi then instructed Manala that if he really wants to be a king he must pursue Ndzundza and bring him back to the royal household and if Ndzundza refuses to come back Manala should kill him.

Manala caught up with Ndzundza who was with Thombeni (Kekana) and Skhosana (Masombuka), his half brothers, at Masongololo around Cullinan. The two factions fought at Cullinan. Manala and his supporters returned home to replenish their provisions. Upon their return, they caught up with Ndzundza at Bhalule River (Oliphants River). Manala did not kill Ndzundza but an old woman called NoQoli from a Mnguni family mediated between the two brothers.

An agreement was reached whereby Manala surrendered the kingship to Ndzundza. It was further agreed that henceforth their daughters would inter-marry, a practice which later died out. The agreement was called “isivumelwano sakoNoQoli” and hence the Mnguni family was later called Msiza because they helped Ndzundza and Manala not to kill each other. Ndzundza never returned to the royal household but settled across the Bhalule River with his followers. Ndzundza settled across the Bhalule River whilst Manala returned to KwaMnyamana and each ruled separately.

Dlomu the son of Skhube went to Emboland, and became the father of the amaNdebele clan in Hlubiland which were later dominated by King Matiwane of the Hlubis. Some of Dlomu’s descendants later joined the Manala and Ndzundza under the shield of Skhosana. Mhwaduba formed a Batswana traditional community and became the originator of the Bahwaduba clan (Mhwaduba of Bakgatla Ba Lekhuleni).

Thombeni left and joined Ndzundza but later hived along the Olifants River and established the Gegana (Kekana) traditional community in Zebediela known as Matebele a Moletlane and later the Mthombeni traditional community among VaTsonga. Sibasa left and joined the VhaVenda community and was later known as Tshivhase amongst the Venda nation. Mphafuli (later called Mphaphuli) joined Sibasa and usurped the leadership of the Vhavenda traditional community.

Ndebele Kings

Manala

King Makhosonke II

Ndzunza

King Mabhoko III

Social and cultural life

Internal political and social structures

Ndebele authority structures were similar to those of their Zulu cousins. The authority over a tribe was vested in the tribal head (iKosi), assisted by an inner or family council (iimphakathi). Wards (izilindi) were administered by ward heads and the family groups within the wards were governed by the heads of the families. The residential unit of each family was called an umuzi. The umuzi usually consisted of a family head (umnumzana) with his wife and unmarried children. If he had more than one wife, the umuzi was divided into two halves, a right and a left half, to accommodate the different wives.

An umuzi sometimes grew into a more complex dwelling unit when the head's married sons and younger brothers joined the household. Every tribe consisted of a number of patrilineal clans or izibongo. This meant that every clan consisted of a group of individuals who shared the same ancestor in the paternal line.

Personal adornment

Ndebele women traditionally adorned themselves with a variety of ornaments, each symbolising her status in society. After marriage, dresses became increasingly elaborate and spectacular. In earlier times, the Ndebele wife would wear copper and brass rings around her arms, legs and neck, symbolising her bond and faithfulness to her husband, once her home was built. She would only remove the rings after his death. The rings (called idzila) were believed to have strong ritual powers. Husbands used to provide their wives with rings; the richer the husband, the more rings the wife would wear. Today, it is no longer common practice to wear these rings permanently.

In addition to the rings, married women also wore neck hoops made of grass (called isirholwani) twisted into a coil and covered in beads, particularly for ceremonial occasions. Linrholwani are sometimes worn as neckpieces and as leg and arm bands by newly wed women whose husbands have not yet provided them with a home, or by girls of marriageable age after the completion of their initiation ceremony (ukuthomba). Married women also wore a five-fingered apron (called an itjhorholo) to mark the culmination of the marriage, which only takes place after the birth of the first child. The marriage blanket (untsurhwana) worn by married women was decorated with beadwork to record significant events throughout the woman's lifetime.

For example, long beaded strips signified that the woman's son was undergoing the initiation ceremony and indicated that the woman had now attained a higher status in Ndebele society. It symbolised joy because her son had achieved manhood as well as the sorrow at losing him to the adult world. A married woman always wore some form of head covering as a sign of respect for her husband. These ranged from a simple beaded headband or a knitted cap to elaborate beaded headdresses (amacubi). Boys usually ran around naked or wore a small front apron of goatskin. However, girls wore beaded aprons or beaded wraparound skirts from an early age. For rituals and ceremonies, Ndebele men adorned themselves with ornaments made for them by their wives.

Arts and craft

Ndebele art has always been an important identifying characteristic of the Ndebele. Apart from its aesthetic appeal it has a cultural significance that serves to reinforce the distinctive Ndebele identity. The Ndebele's essential artistic skill has always been understood to be the ability to combine exterior sources of stimulation with traditional design concepts borrowed from their ancestors. Ndebele artists also demonstrated a fascination with the linear quality of elements in their environment and this is depicted in their artwork. Painting was done freehand, without prior layouts, although the designs were planned beforehand.

The characteristic symmetry, proportion and straight edges of Ndebele decorations were done by hand without the help of rulers and squares. Ndebele women were responsible for painting the colourful and intricate patterns on the walls of their houses. This presented the traditionally subordinate wife with an opportunity to express her individuality and sense of self-worth. Her innovativeness in the choice of colours and designs set her apart from her peer group. In some instances, the women also created sculptures to express themselves.

The back and side walls of the house were often painted in earth colours and decorated with simple geometric shapes that were shaped with the fingers and outlined in black. The most innovative and complex designs were painted, in the brightest colours, on the front walls of the house. The front wall that enclosed the courtyard in front of the house formed the gateway (izimpunjwana) and was given special care. Windows provided a focal point for mural designs and their designs were not always symmetrical. Sometimes, makebelieve windows are painted on the walls to create a focal point and also as a mechanism to relieve the geometric rigidity of the wall design. Simple borders painted in a dark colour, lined with white, accentuated less important windows in the inner courtyard and in outside walls.

Contemporary Ndebele artists make use of a wider variety of colours (blues, reds, greens and yellows) than traditional artists were able to, mainly because of their commercial availability. Traditionally, muted earth colours, made from ground ochre, and different natural-coloured clays, in white, browns, pinks and yellows, were used. Black was derived from charcoal. Today, bright colours are the order of the day. As Ndebele society became more westernised, the artists started reflecting this change of their society in their paintings. Another change is the addition of stylised representational forms to the typical traditional abstract geometric designs. Many Ndebele artists have now also extended their artwork to the interior of houses. Ndebele artists also produce other crafts such as sleeping mats and isingolwani.

Iinrholwani (colourful neck hoops) are made by winding grass into a hoop, binding it tightly with cotton and decorating it with beads. In order to preserve the grass and to enable the hoop to retain its shape and hardness, the hoop is boiled in sugar water and left in the hot sun for a few days. A further outstanding characteristic of the Ndebele is their beadwork. Beadwork is intricate and time-consuming and requires a deft hand and good eyesight. This pastime has long been a social practice in which the women engaged after their chores were finished but today, many projects involve the production of these items for sale to the public.

Special occasions

Initiation

In Ndebele culture, the initiation rite, symbolising the transition from childhood to adulthood, plays an important role. Initiation schools for boys are held every four years and for girls, as soon as they get into puberty stage. During the period of initiation, relatives and friends come from far and wide to join in the ceremonies and activities associated with initiation. Boys are initiated as a group when they are about 18 years of age when a special regiment (iintanga) is set up and led by a boy of high social rank. Each regiment has a distinguishing name. Among the Ndzundza tribe there is a cycle of 15 such regimental names, allocated successively, and among the Manala there is a cycle of 13 such names.

During initiation girls wear an array of colourful beaded hoops (called iinrholwani) around their legs, arms, waist and neck. The girls are kept in isolation and are prepared and trained to become homemakers and matriarchs. The coming-out ceremony marks the conclusion of the initiation school and the girls then wear stiff rectangular aprons (called iphephetu), beaded in geometric and often three-dimensional patterns, to celebrate the event. After initiation, these aprons are replaced by stiff, square ones, made from hardened leather and adorned with beadwork.

Courtship and marriage

Marriages were only concluded between members of different clans, that is between individuals who did not have the same clan name. However, a man could marry a woman from the same family as his paternal grandmother. The prospective bride was kept secluded for two weeks before the wedding in a specially made structure in her parents' house, to shield her from men's eyes.

When the bride emerged from her seclusion, she was wrapped in a blanket and covered by an umbrella that was held for her by a younger girl called(Ipelesi) who also attended to her other needs. On her marriage, the bride was given a marriage blanket, which she would, in time, adorn with beadwork, either added to the blanket's outer surface or woven into the fabric. After the wedding, the couple lived in the area belonging to the husband's clan. Women retained the clan name of their fathers but children born of the marriage took their father's clan name.

References

^ Skhosana, Philemon Buti (2009). "3". The Linguistic Relationship between Southern and Northern Ndebele (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-17..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ www.northernndebele.blogspot.com

Further reading

Ndebele: The art of an African tribe, 1986. Margaret Courtney-Clarke, London: Thames & Hudson.

ISBN 0-500-28387-7

Ndebele Images, 1983. Natalie Knight & Suzanne Priebatsch, Natalie Knight Productions Ltd. ASIN: B0026835HO

Art of the Ndebele: The Evolution of a Cultural Identity, 1998. Natalie Knight & Suzanne Priebatsch, Natalie Knight Productions Ltd.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ndebele. |

- http://www.sahistory.org.za/article/people-south-africa-ndebele

- http://www.krugerpark.co.za/africa_ndebele.html

- http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Ndebele.aspx

- http://www.mongabay.com/indigenous_ethnicities/languages/languages/Ndebele.html