Necessity and sufficiency

In logic, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between statements. For example, in the conditional statement "If P then Q", we say that "Q is necessary for P" because P cannot be true unless Q is true. Similarly, we say that "P is sufficient for Q" because P being true always implies that Q is true, but P not being true does not always imply that Q is not true.[1]

The assertion that a statement is a "necessary and sufficient" condition of another means that the former statement is true if and only if the latter is true. That is, the two statements must be either simultaneously true or simultaneously false.[2][3][4]

In ordinary English, "necessary" and "sufficient" indicate relations between conditions or states of affairs, not statements. Being a male sibling is a necessary and sufficient condition for being a brother.

Contents

1 Definitions

2 Necessity

3 Sufficiency

4 Relationship between necessity and sufficiency

5 Simultaneous necessity and sufficiency

6 See also

6.1 Argument forms involving necessary and sufficient conditions

6.1.1 Valid forms of argument

6.1.2 Invalid forms of argument (i.e., fallacies)

7 See also

8 References

9 External links

Definitions

In the conditional statement, "if S, then N", the expression represented by S is called the antecedent and the expression represented by N is called the consequent. This conditional statement may be written in many equivalent ways, for instance, "N if S", "S only if N", "S implies N", "N is implied by S", S → N , S ⇒ N, or "N whenever S".[5]

In the above situation, we say that N is a necessary condition for S. In common language this is saying that if the conditional statement is a true statement, then the consequent N must be true if S is to be true (see third column of "truth table" immediately below). Phrased differently, the antecedent S cannot be true without N being true. For example, in order for someone to be called Socrates, it is necessary for that someone to be Named.

In the above situation, we can also say S is a sufficient condition for N. Again, consider the third column of the truth table immediately below. If the conditional statement is true, then if S is true, N must be true; whereas if the conditional statement is true and N is true, then S may be true or be false. In common terms, "S guarantees N". Continuing the example, knowing that someone is called Socrates is sufficient to know that someone has a Name.

A necessary and sufficient condition requires that both of the implications S⇒N{displaystyle SRightarrow N}

.mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} S | N | S⇒N{displaystyle SRightarrow N}  | S⇐N{displaystyle SLeftarrow N}  | S⇔N{displaystyle SLeftrightarrow N}  |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | F |

| F | T | T | F | F |

| F | F | T | T | T |

Necessity

The sun being above the horizon is a necessary condition for direct sunlight; but it is not a sufficient condition, as something else may be casting a shadow, e.g., the moon in the case of an eclipse.

The assertion that Q is necessary for P is colloquially equivalent to "P cannot be true unless Q is true" or "if Q is false, then P is false". By contraposition, this is the same thing as "whenever P is true, so is Q".

The logical relation between P and Q is expressed as "if P, then Q" and denoted "P ⇒ Q" (P implies Q). It may also be expressed as any of "P only if Q", "Q, if P", "Q whenever P", and "Q when P". One often finds, in mathematical prose for instance, several necessary conditions that, taken together, constitute a sufficient condition, as shown in Example 5.

- Example 1

- For it to be true that "John is a bachelor", it is necessary that it be also true that he is

- unmarried,

- male,

- adult,

- since to state "John is a bachelor" implies John has each of those three additional predicates.

- Example 2

- For the whole numbers greater than two, being odd is necessary to being prime, since two is the only whole number that is both even and prime.

- Example 3

- Consider thunder, the sound caused by lightning. We say that thunder is necessary for lightning, since lightning never occurs without thunder. Whenever there's lightning, there's thunder. The thunder does not cause the lightning (since lightning causes thunder), but because lightning always comes with thunder, we say that thunder is necessary for lightning. (That is, in its formal sense, necessity doesn't imply causality.)

- Example 4

- Being at least 30 years old is necessary for serving in the U.S. Senate. If you are under 30 years old, then it is impossible for you to be a senator. That is, if you are a senator, it follows that you are at least 30 years old.

- Example 5

- In algebra, for some set S together with an operation ⋆{displaystyle star }

to form a group, it is necessary that ⋆{displaystyle star }

be associative. It is also necessary that S include a special element e such that for every x in S it is the case that e ⋆{displaystyle star }

x and x ⋆{displaystyle star }

e both equal x. It is also necessary that for every x in S there exist a corresponding element x″ such that both x ⋆{displaystyle star }

x″ and x″ ⋆{displaystyle star }

x equal the special element e. None of these three necessary conditions by itself is sufficient, but the conjunction of the three is.

Sufficiency

That a train runs on schedule can be a sufficient condition for arriving on time (if one boards the train and it departs on time, then one will arrive on time); but it is not always a necessary condition, since there are other ways to travel (if the train does not run to time, one could still arrive on time through other means of transport).

If P is sufficient for Q, then knowing P to be true is adequate grounds to conclude that Q is true; however, knowing P to be false does not meet a minimal need to conclude that Q is false.

The logical relation is, as before, expressed as "if P, then Q" or "P ⇒ Q". This can also be expressed as "P only if Q", "P implies Q" or several other variants. It may be the case that several sufficient conditions, when taken together, constitute a single necessary condition, as illustrated in example 5.

- Example 1

- "John is a king" implies that John is male. So knowing that it is true that John is a king is sufficient to know that he is a male.

- Example 2

- A number's being divisible by 4 is sufficient (but not necessary) for its being even, but being divisible by 2 is both sufficient and necessary.

- Example 3

- An occurrence of thunder is a sufficient condition for the occurrence of lightning in the sense that hearing thunder, and unambiguously recognizing it as such, justifies concluding that there has been a lightning bolt.

- Example 4

- If the U.S. Congress passes a bill, the president's signature of the bill is sufficient to make it law. Note that the case whereby the president did not sign the bill, e.g. through exercising a presidential veto, does not mean that the bill has not become law (it could still have become law through a congressional override).

- Example 5

- That the center of a playing card should be marked with a single large spade (♠) is sufficient for the card to be an ace. Three other sufficient conditions are that the center of the card be marked with a diamond (♦), heart (♥), or club (♣), respectively. None of these conditions is necessary to the card's being an ace, but their disjunction is, since no card can be an ace without fulfilling at least (in fact, exactly) one of the conditions.

Relationship between necessity and sufficiency

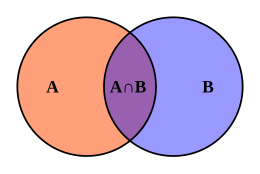

Being in the purple region is sufficient for being in A, but not necessary. Being in A is necessary for being in the purple region, but not sufficient. Being in A and being in B is necessary and sufficient for being in the purple region.

A condition can be either necessary or sufficient without being the other. For instance, being a mammal (N) is necessary but not sufficient to being human (S), and that a number x{displaystyle x}

A condition can be both necessary and sufficient. For example, at present, "today is the Fourth of July" is a necessary and sufficient condition for "today is Independence Day in the United States". Similarly, a necessary and sufficient condition for invertibility of a matrix M is that M has a nonzero determinant.

Mathematically speaking, necessity and sufficiency are dual to one another. For any statements S and N, the assertion that "N is necessary for S" is equivalent to the assertion that "S is sufficient for N". Another facet of this duality is that, as illustrated above, conjunctions (using "and") of necessary conditions may achieve sufficiency, while disjunctions (using "or") of sufficient conditions may achieve necessity. For a third facet, identify every mathematical predicate N with the set T(N) of objects, events, or statements for which N holds true; then asserting the necessity of N for S is equivalent to claiming that T(N) is a superset of T(S), while asserting the sufficiency of S for N is equivalent to claiming that T(S) is a subset of T(N).

Simultaneous necessity and sufficiency

To say that P is necessary and sufficient for Q is to say two things:

- that P is necessary for Q, P⇐Q{displaystyle PLeftarrow Q}

, and that P is sufficient for Q, P⇒Q{displaystyle PRightarrow Q}

.

- equivalently, it may be understood to say that P and Q is necessary for the other, P⇒Q∧Q⇒P{displaystyle PRightarrow Qland QRightarrow P}

, which can also be stated as each is sufficient for or implies the other.

One may summarize any, and thus all, of these cases by the statement "P if and only if Q", which is denoted by P⇔Q{displaystyle PLeftrightarrow Q}

For example, in graph theory a graph G is called bipartite if it is possible to assign to each of its vertices the color black or white in such a way that every edge of G has one endpoint of each color. And for any graph to be bipartite, it is a necessary and sufficient condition that it contain no odd-length cycles. Thus, discovering whether a graph has any odd cycles tells one whether it is bipartite and conversely. A philosopher[6] might characterize this state of affairs thus: "Although the concepts of bipartiteness and absence of odd cycles differ in intension, they have identical extension.[7]

In mathematics, theorems are often stated in the form "P is true if and only if Q is true". Their proofs normally first prove sufficiency, e.g. P⇒Q{displaystyle PRightarrow Q}

- either directly, assuming Q is true and demonstrating that the Q circle is located within P, or

contrapositively, that is demonstrating that stepping outside circle of P, we fall out the Q: assuming not P, not Q results.

This proves that the circles for Q and P match on the Venn diagrams above.

Because, as explained in previous section, necessity of one for the other is equivalent to sufficiency of the other for the first one, e.g. P⇐Q{displaystyle PLeftarrow Q}

See also

- Causality

- Material implication (disambiguation)

- Wason selection task

- Closed concept

Argument forms involving necessary and sufficient conditions

Valid forms of argument

- Modus ponens

- Modus tollens

Invalid forms of argument (i.e., fallacies)

- Affirming the consequent

- Denying the antecedent

See also

- Principle of sufficient reason

References

^ Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). Proofs and Fundamentals: A First Course in Abstract Mathematics. Springer. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-4419-7126-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Betz, Frederick (2011). Managing Science: Methodology and Organization of Research. New York: Springer. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-4419-7487-7.

^ Manktelow, K. I. (1999). Reasoning and Thinking. East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press. ISBN 0-86377-708-2.

^ Asnina, Erika; Osis, Janis & Jansone, Asnate (2013). "Formal Specification of Topological Relations". Databases and Information Systems VII: 175. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-161-8-175.

^ Devlin, Keith (2004), Sets, Functions and Logic / An Introduction to Abstract Mathematics (3rd ed.), Chapman & Hall, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-1-58488-449-1

^ Stanford University primer, 2006.

^ "Meanings, in this sense, are often called intensions, and things designated, extensions. Contexts in which extension is all that matters are, naturally, called extensional, while contexts in which extension is not enough are intensional. Mathematics is typically extensional throughout." Stanford University primer, 2006.

External links

- Critical thinking web tutorial: Necessary and Sufficient Conditions

- Simon Fraser University: Concepts with examples