Acetylcysteine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˌsiːtəlˈsɪstiiːn/ and similar (/əˌsɛtəl-, ˌæsɪtəl-, -tiːn/) |

| Trade names | Acetadote, Fluimucil, Mucomyst, others |

| Synonyms | N-acetylcysteine; N-acetyl-L-cysteine; NALC; NAC |

AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, injection, inhalation |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 10% (Oral)[2] |

| Protein binding | 50 to 83%[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 5.6 hours[3] |

| Excretion | Renal (30%),[1] faecal (3%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.545 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

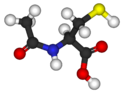

| Formula | C5H9NO3S |

| Molar mass | 163.195 |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| Specific rotation | +5° (c = 3% in water)[5] |

| Melting point | 109 to 110 °C (228 to 230 °F) [5] |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

.mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} (verify) | |

Acetylcysteine, also known as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), is a medication that is used to treat paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose, and to loosen thick mucus in individuals with cystic fibrosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[1] It can be taken intravenously, by mouth, or inhaled as a mist.[1] Some people use it as a dietary supplement.[6][7]

Common side effects include nausea and vomiting when taken by mouth.[1] The skin may occasionally become red and itchy with either form.[1] A non-immune type of anaphylaxis may also occur.[1] It appears to be safe in pregnancy.[1] For paracetamol overdose, it works by increasing the level of glutathione, an antioxidant that can neutralise the toxic breakdown products of paracetamol.[1] When inhaled, it acts as a mucolytic by decreasing the thickness of mucus.[8]

Acetylcysteine was initially patented in 1960 and licensed for use in 1968.[9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[10] It is available as a generic medication and is inexpensive.[11]

Contents

1 Uses

1.1 Paracetamol overdose

1.2 Mucolytic therapy

1.3 Kidney disease

1.4 Haemorrhagic cystitis

1.5 Obstructive lung disease

1.6 Psychiatry

1.7 Microbiological use

1.8 Other uses

2 Side effects

3 Pharmacology

3.1 Pharmacodynamics

3.2 Pharmacokinetics

4 Chemistry

5 Dosage forms

6 Research

7 References

8 External links

Uses

Acetylcysteine as effervescent tablet

Paracetamol overdose

Intravenous and oral formulations of acetylcysteine are available for the treatment of paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose.[12] When paracetamol is taken in large quantities, a minor metabolite called N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) accumulates within the body. It is normally conjugated by glutathione, but when taken in excess, the body's glutathione reserves are not sufficient to inactivate the toxic NAPQI. This metabolite is then free to react with key hepatic enzymes, thereby damaging liver cells. This may lead to severe liver damage and even death by acute liver failure.

In the treatment of acetaminophen overdose, acetylcysteine acts to maintain or replenish depleted glutathione reserves in the liver and enhance non-toxic metabolism of acetaminophen.[13] These actions serve to protect liver cells from NAPQI toxicity. It is most effective in preventing or lessening hepatic injury when administered within 8–10 hours after overdose.[13] Research suggests that the rate of liver toxicity is approximately 3% when acetylcysteine is administered within 10 hours of overdose.[12]

Although both IV and oral acetylcysteine are equally effective for this indication, oral administration is poorly tolerated because high oral doses are required due to low oral bioavailability,[14] because of its very unpleasant taste and odour, and because of adverse effects, particularly nausea and vomiting. Prior pharmacokinetic studies of acetylcysteine did not consider acetylation as a reason for the low bioavailability of acetylcysteine.[15] Oral acetylcysteine is identical in bioavailability to cysteine precursors.[15] However, 3% to 6% of people given intravenous acetylcysteine show a severe, anaphylaxis-like allergic reaction, which may include extreme breathing difficulty (due to bronchospasm), a decrease in blood pressure, rash, angioedema, and sometimes also nausea and vomiting.[16] Repeated doses of intravenous acetylcysteine will cause these allergic reactions to progressively worsen in these people.

Several studies have found this anaphylaxis-like reaction to occur more often in people given IV acetylcysteine despite serum levels of paracetamol not high enough to be considered toxic.[17][18][19][20]

Mucolytic therapy

Inhaled acetylcysteine has been used for mucolytic ("mucus-dissolving") therapy in addition to other therapies in respiratory conditions with excessive and/or thick mucus production. It is also used post-operatively, as a diagnostic aid, and in tracheotomy care. It may be considered ineffective in cystic fibrosis.[21] A 2013 Cochrane review in cystic fibrosis found no evidence of benefit.[22]

Kidney disease

Some reviews found that prior administration of acetylcysteine decreases radiocontrast induced kidney disease,[23][24] whereas another found questionable effects.[25]

Despite the conflicting research outcomes, the 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines suggest the use of oral acetylcysteine for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in high-risk individuals, given its potential for benefit, low likelihood of adverse effects, and low cost.[26]

Haemorrhagic cystitis

Acetylcysteine has been used for cyclophosphamide-induced haemorrhagic cystitis, although mesna is generally preferred due to the ability of acetylcysteine to diminish the effectiveness of cyclophosphamide.[27][28]

Obstructive lung disease

Acetylcysteine is used in the treatment of obstructive lung disease as an adjuvant treatment.[29][30][31]

Psychiatry

Acetylcysteine has been successfully tried as a treatment for a number of psychiatric disorders.[32][33][34] A systematic review from 2015, and several earlier medical reviews, indicated that there is favorable evidence for N-acetylcysteine efficacy in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, specific drug addictions (cocaine), and a certain form of epilepsy (progressive myoclonic).[32][33][35][36][37][38] Tentative evidence also supports use in cannabis use disorder.[39]

Evidence to date does not support the efficacy for N-acetylcysteine in treating addictions to gambling, methamphetamine, or nicotine, although pilot controlled data are encouraging.[35] Based upon preclinical evidence and limited clinical evidence, NAC appears to normalize glutamate neurotransmission into the nucleus accumbens and other brain structures, in part by upregulating the expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2), a.k.a. glutamate transporter 1 (GLT1), in individuals with addiction.[40] While NAC has been demonstrated to modulate glutamate neurotransmission in adult humans who are addicted to cocaine, NAC does not appear to modulate glutamate neurotransmission in healthy adult humans.[40]

NAC has been hypothesized to exert beneficial effects through its modulation of glutamate and dopamine neurotransmission as well as its antioxidant properties.[33]

Microbiological use

Acetylcysteine can be used in Petroff's method i.e. liquefaction and decontamination of sputum, in preparation for recovery of mycobacterium.[41] It also displays significant antiviral activity against the influenza A viruses.[42]

Acetylcysteine has bactericidal properties and breaks down bacterial biofilms of clinically relevant pathogens including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.[43]

Other uses

Acetylcysteine has been used to complex palladium, to help it dissolve in water. This helps to remove palladium from drugs or precursors synthesized by palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions.[44]

Side effects

The most commonly reported adverse effects for IV formulations of acetylcysteine are rash, urticaria, and itchiness.[13] Up to 18% of patients have been reported to experience anaphylaxis reaction, which are defined as rash,

hypotension, wheezing, and/or shortness of breath. Lower rates of anaphylactoid reactions have been reported with slower rates of infusion.

Adverse effects for inhalational formulations of acetylcysteine include nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, fever, rhinorrhea, drowsiness, clamminess, chest tightness, and bronchoconstriction. Although infrequent, bronchospasm has been reported to occur unpredictably in some patients.[45]

Adverse effects for oral formulations of acetylcysteine have been reported to include nausea, vomiting, rash, and fever.[45]

Large doses in a mouse model showed that acetylcysteine could potentially cause damage to the heart and lungs.[46] They found that acetylcysteine was metabolized to S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine (SNOAC), which increased blood pressure in the lungs and right ventricle of the heart (pulmonary artery hypertension) in mice treated with acetylcysteine. The effect was similar to that observed following a 3-week exposure to an oxygen-deprived environment (chronic hypoxia). The authors also found that SNOAC induced a hypoxia-like response in the expression of several important genes both in vitro and in vivo.

The implications of these findings for long-term treatment with acetylcysteine have not yet been investigated. The dose used by Palmer and colleagues was dramatically higher than that used in humans, the equivalent of about 20 grams per day.[46][47] Nonetheless, positive effects on age-diminished control of respiration (the hypoxic ventilatory response) have been observed previously in human subjects at more moderate doses.[48]

Although N-acetylcysteine prevented liver damage when taken before alcohol, when taken four hours after alcohol it made liver damage worse in a dose-dependent fashion.[49]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Acetylcysteine serves as a prodrug to L-cysteine.

L-cysteine is a precursor to the biologic antioxidant glutathione. Hence administration of acetylcysteine replenishes glutathione stores.[50]

– Glutathione, along with oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), have been found to bind to the glutamate recognition site of the NMDA and AMPA receptors (via their γ-glutamyl moieties), and may be endogenous neuromodulators.[51][52] At millimolar concentrations, they may also modulate the redox state of the NMDA receptor complex.[52] In addition, glutathione has been found to bind to and activate ionotropic receptors that are different from any other excitatory amino acid receptor, and which may constitute glutathione receptors, potentially making it a neurotransmitter.[53] As such, since N-acetylcysteine is a prodrug of glutathione, it may modulate all of the aforementioned receptors as well.

– Glutathione also modulates the NMDA receptor by acting at the redox site.[33][54]

L-cysteine also serves as a precursor to cystine which in turn serves as a substrate for the cystine-glutamate antiporter on astrocytes hence increasing glutamate release into the extracellular space. This glutamate in turn acts on mGluR2/3 receptors, and at higher doses of acetylcysteine, mGluR5.[55][56]

Acetylcysteine also possesses some anti-inflammatory effects possibly via inhibiting NF-κB and modulating cytokine synthesis.[33]

Pharmacokinetics

Acetylcysteine is extensively liver metabolized, CYP450 minimal, urine excretion is 22-30% with a half-life of 5.6 hours in adults and 11 hours in neonates.

Chemistry

Acetylcysteine is the N-acetyl derivative of the amino acid L-cysteine, and is a precursor in the formation of the antioxidant glutathione in the body. The thiol (sulfhydryl) group confers antioxidant effects and is able to reduce free radicals.

N-acetyl-L-cysteine is soluble in water and alcohol, and practically insoluble in chloroform and ether.[57]

It is a white to white with light yellow cast powder, and has a pKa of 9.5 at 30 °C.[5]

Dosage forms

Acetylcysteine is available in different dosage forms for different indications:

- Solution for inhalation (Assist, Mucomyst, Mucosil) – inhaled for mucolytic therapy or ingested for nephroprotective effect (kidney protection)

Intravenous injection (Assist, Parvolex, Acetadote) – treatment of paracetamol/acetaminophen overdose- Oral solution – various indications.

- Effervescent tablets

- Ocular solution - for mucolytic therapy

- Tablets - sometimes in a sustained release formula sold as a nutritional supplement

- Capsules

The IV injection and inhalation preparations are, in general, prescription only, whereas the oral solution and the effervescent tablets are available over the counter in many countries. Acetylcysteine is available as a health supplement in the United States, typically in capsule form.

Research

While many antioxidants have been researched to treat a large number of diseases by reducing the negative effect of oxidative stress, acetylcysteine is one of the few that has yielded promising results, and is currently already approved for the treatment of paracetamol overdose.[58]

- In mouse mdx models of Duchenne's muscular dystrophy, treatment with 1-2% acetylcysteine in drinking water significantly reduces muscle damage and improves strength.[58]

- It is being studied in conditions, such as autism, where cysteine and related sulfur amino acids may be depleted due to multifactorial dysfunction of methylation pathways involved in methionine catabolism.[59]

- Acetylcysteine in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial appears to reduce the effects of blast induced mild traumatic brain and neurological injury in soldiers.[60] Animal studies have also demonstrated its efficacy in reducing the damage associated with moderate traumatic brain or spinal injury, and also ischaemia-induced brain injury. In particular, it has been demonstrated to reduce neuronal losses and to improve cognitive and neurological outcomes associated with these traumatic events.[34]

- It has been suggested that acetylcysteine may help people with Samter's triad by increasing levels of glutathione allowing faster breakdown of salicylates, although there is no evidence that it is of benefit.[61]

- It has been shown to help women with PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) to reduce insulin problems and possibly improve fertility.[62]

- Small studies have shown acetylcysteine to be of benefit to people with blepharitis,[63] and it has been shown to reduce ocular soreness caused by Sjögren's syndrome.[64]

- It has been shown effective in the treatment of Unverricht-Lundborg disease in an open trial in four patients. A marked decrease in myoclonus and some normalization of somatosensory evoked potentials with acetylcysteine treatment has been documented.[65][66]

- Addiction to certain addictive drugs (e.g., cocaine, heroin, alcohol, and nicotine) is correlated with a persistent reduction in the expression of excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc);[40] the reduced expression of EAAT2 in this region is implicated in addictive drug-seeking behavior.[40] In particular, the long-term dysregulation of glutamate neurotransmission in the NAcc of addicts is associated with an increase in vulnerability to relapse after re-exposure to the addictive drug or its associated drug cues.[40] Drugs that help to normalize the expression of EAAT2 in this region, such as N-acetylcysteine, have been proposed as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of addiction to cocaine, nicotine, alcohol, and other drugs.[40]

- It has been tested for the reduction of hangover symptoms, but one clinical trial found no significant change between those receiving the drug and placebo.[67]

References

^ abcdefghij "Acetylcysteine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Stockley RA (2008). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease a Practical Guide to Management. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 750. ISBN 9780470755280. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ "ACETADOTE (acetylcysteine) injection, solution [Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc.]". DailyMed. Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. June 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

^ "L-Cysteine, N-acetyl- - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 25 March 2005. Identification. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

^ abc "N-ACETYL-L-CYSTEINE Product Information" (PDF). Sigma. Sigma-aldrich. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

^ Talbott, Shawn M. (2012). A Guide to Understanding Dietary Supplements. Routledge. p. 469. ISBN 9781136805707. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ "Cysteine". University of Maryland Medical Center. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ Sadowska, Anna M; Verbraecken, J; Darquennes, K; De Backer, WA (December 2006). "Role of N-acetylcysteine in the management of COPD". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 1 (4): 425–434. ISSN 1176-9106. PMC 2707813. PMID 18044098.

^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-Based Drug Discovery. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 544. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

^ Baker E (2014). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. p. Acetylcysteine. ISBN 9780702055157. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ ab Green JL, Heard KJ, Reynolds KM, Albert D (May 2013). "Oral and Intravenous Acetylcysteine for Treatment of Acetaminophen Toxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 14 (3): 218–26. doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.4.6885. PMC 3656701. PMID 23687539.

^ abc "Acetadote Package Insert" (PDF). FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

^ Borgström L, Kågedal B, Paulsen O (1986). "Pharmacokinetics of N-acetylcysteine in man". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 31 (2): 217–22. doi:10.1007/bf00606662. PMID 3803419.

^ ab Dilger RN, Baker DH (Jul 2007). "Oral N-acetyl-L-cysteine is a safe and effective precursor of cysteine". Journal of Animal Science. 85 (7): 1712–8. doi:10.2527/jas.2006-835. PMID 17371789.

^ Kanter MZ (Oct 2006). "Comparison of oral and i.v. acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen poisoning". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 63 (19): 1821–7. doi:10.2146/ajhp060050. PMID 16990628.

^ Dawson AH, Henry DA, McEwen J (Mar 1989). "Adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine during treatment for paracetamol poisoning". The Medical Journal of Australia. 150 (6): 329–31. PMID 2716644.

^ Bailey B, McGuigan MA (Jun 1998). "Management of anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 31 (6): 710–5. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70229-X. PMID 9624310.

^ Schmidt LE, Dalhoff K (Jan 2001). "Risk factors in the development of adverse reactions to N-acetylcysteine in patients with paracetamol poisoning". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 51 (1): 87–91. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2001.01305.x. PMC 2014432. PMID 11167669.

^ Lynch RM, Robertson R (Jan 2004). "Anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine: a prospective case controlled study". Accident and Emergency Nursing. 12 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1016/j.aaen.2003.07.001. PMID 14700565.

^ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

^ Tam, J; Nash, EF; Ratjen, F; Tullis, E; Stephenson, A (12 July 2013). "Nebulized and oral thiol derivatives for pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD007168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007168.pub3. PMID 23852992.

^ Wang, N; Qian, P; Kumar, S; Yan, TD; Phan, K (15 April 2016). "The effect of N-acetylcysteine on the incidence of contrast-induced kidney injury: A systematic review and trial sequential analysis". International Journal of Cardiology. 209: 319–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.083. PMID 26922293.

^ Su, X; Xie, X; Liu, L; Lv, J; Song, F; Perkovic, V; Zhang, H (January 2017). "Comparative Effectiveness of 12 Treatment Strategies for Preventing Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Network Meta-analysis". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 69 (1): 69–77. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.07.033. PMID 27707552.

^ Chalikias, G; Drosos, I; Tziakas, DN (October 2016). "Prevention of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: an Update". Cardiovascular drugs and therapy. 30 (5): 515–524. doi:10.1007/s10557-016-6683-0. PMID 27541275.

^ Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. "KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

^ Palma PC, Villaça Júnior CJ, Netto Júnior NR (1986). "N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of cyclophosphamide induced haemorrhagic cystitis". International Surgery. 71 (1): 36–7. PMID 3522468.

^ Hemorrhagic Cystitis~treatment at eMedicine

^ Grandjean EM, Berthet P, Ruffmann R, Leuenberger P (Feb 2000). "Efficacy of oral long-term N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchopulmonary disease: a meta-analysis of published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials". Clinical Therapeutics. 22 (2): 209–21. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88479-9. PMID 10743980.

^ Stey C, Steurer J, Bachmann S, Medici TC, Tramèr MR (Aug 2000). "The effect of oral N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchitis: a quantitative systematic review". The European Respiratory Journal. 16 (2): 253–62. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b12.x. PMID 10968500.

^ Poole PJ, Black PN (May 2001). "Oral mucolytic drugs for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review". BMJ. 322 (7297): 1271–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1271. PMC 31920. PMID 11375228.

^ ab Dean O, Giorlando F, Berk M (Mar 2011). "N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry: current therapeutic evidence and potential mechanisms of action". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 36 (2): 78–86. doi:10.1503/jpn.100057. PMC 3044191. PMID 21118657.

^ abcde Berk M, Malhi GS, Gray LJ, Dean OM (Mar 2013). "The promise of N-acetylcysteine in neuropsychiatry". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 34 (3): 167–77. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.01.001. PMID 23369637.

^ ab Bavarsad Shahripour R, Harrigan MR, Alexandrov AV (Mar 2014). "N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in neurological disorders: mechanisms of action and therapeutic opportunities". Brain and Behavior. 4 (2): 108–22. doi:10.1002/brb3.208. PMC 3967529. PMID 24683506.

^ ab Slattery J, Kumar N, Delhey L, Berk M, Dean O, Spielholz C, Frye R (Aug 2015). "Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 55: 294–321. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.015. PMID 25957927.

^ Berk M, Dean OM, Cotton SM, Jeavons S, Tanious M, Kohlmann K, Hewitt K, Moss K, Allwang C, Schapkaitz I, Robbins J, Cobb H, Ng F, Dodd S, Bush AI, Malhi GS (Jun 2014). "The efficacy of adjunctive N-acetylcysteine in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 75 (6): 628–36. doi:10.4088/JCP.13m08454. PMID 25004186.

^ Oliver G, Dean O, Camfield D, Blair-West S, Ng C, Berk M, Sarris J (Apr 2015). "N-acetyl cysteine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive and related disorders: a systematic review". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 13 (1): 12–24. doi:10.9758/cpn.2015.13.1.12. PMC 4423164. PMID 25912534.

^ Samuni Y, Goldstein S, Dean OM, Berk M (Aug 2013). "The chemistry and biological activities of N-acetylcysteine". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1830 (8): 4117–29. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.016. PMID 23618697.

^ Minarini, A; Ferrari, S; Galletti, M; Giambalvo, N; Perrone, D; Rioli, G; Galeazzi, GM (2 November 2016). "N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: current status and future prospects". Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology: 1–14. doi:10.1080/17425255.2017.1251580. PMID 27766914.

^ abcdef McClure EA, Gipson CD, Malcolm RJ, Kalivas PW, Gray KM (2014). "Potential role of N-acetylcysteine in the management of substance use disorders". CNS Drugs. 28 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0142-x. PMC 4009342. PMID 24442756.

^ Buijtels PC, Petit PL (Jul 2005). "Comparison of NaOH-N-acetyl cysteine and sulfuric acid decontamination methods for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens". Journal of Microbiological Methods. 62 (1): 83–8. doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2005.01.010. PMID 15823396.

^ Geiler J, Michaelis M, Naczk P, Leutz A, Langer K, Doerr HW, Cinatl J (Feb 2010). "N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) inhibits virus replication and expression of pro-inflammatory molecules in A549 cells infected with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus". Biochemical Pharmacology. 79 (3): 413–20. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.025. PMID 19732754.

^ Aslam S, Darouiche RO (Sep 2011). "Role of antibiofilm-antimicrobial agents in controlling device-related infections". The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 34 (9): 752–8. doi:10.5301/ijao.5000024. PMC 3251652. PMID 22094553.

^ Garrett CE, Prasad K (2004). "The Art of Meeting Palladium Specifications in Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Produced by Pd-Catalyzed Reactions". Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 346 (8): 889–900. doi:10.1002/adsc.200404071.

^ ab "Mucomyst Package Insert". Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

^ ab Palmer LA, Doctor A, Chhabra P, Sheram ML, Laubach VE, Karlinsey MZ, Forbes MS, Macdonald T, Gaston B (Sep 2007). "S-nitrosothiols signal hypoxia-mimetic vascular pathology". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (9): 2592–601. doi:10.1172/JCI29444. PMC 1952618. PMID 17786245.

^

"The Overlooked Compound That Saves Lives". Retrieved 8 July 2013. Julius Goepp, MD. Published in Life Extension, May 2010, quote: ". . . the doses they used correspond to a human dose of about 20 grams (20,000 mg) per day."

^ Hildebrandt W, Alexander S, Bärtsch P, Dröge W (Mar 2002). "Effect of N-acetyl-cysteine on the hypoxic ventilatory response and erythropoietin production: linkage between plasma thiol redox state and O(2) chemosensitivity". Blood. 99 (5): 1552–5. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.5.1552. PMID 11861267.

^ Wang AL, Wang JP, Wang H, Chen YH, Zhao L, Wang LS, Wei W, Xu DX (Mar 2006). "A dual effect of N-acetylcysteine on acute ethanol-induced liver damage in mice". Hepatology Research. 34 (3): 199–206. doi:10.1016/j.hepres.2005.12.005. PMID 16439183.

^ "PRODUCT INFORMATION ACETADOTE® CONCENTRATED INJECTION" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Phebra Pty Ltd. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

^ Steullet, P.; Neijt, H.C.; Cuénod, M.; Do, K.Q. (2006). "Synaptic plasticity impairment and hypofunction of NMDA receptors induced by glutathione deficit: Relevance to schizophrenia". Neuroscience. 137 (3): 807–819. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.014. ISSN 0306-4522. PMID 16330153.

^ ab Varga, V.; Jenei, Zs.; Janáky, R.; Saransaari, P.; Oja, S. S. (1997). "Glutathione Is an Endogenous Ligand of Rat Brain N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) and 2-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) Receptors". Neurochemical Research. 22 (9): 1165–1171. doi:10.1023/A:1027377605054. ISSN 0364-3190. PMID 9251108.

^ Oja, S (2000). "Modulation of glutamate receptor functions by glutathione". Neurochemistry International. 37 (2–3): 299–306. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(00)00031-0. ISSN 0197-0186. PMID 10812215.

^ Lavoie S, Murray MM, Deppen P, Knyazeva MG, Berk M, Boulat O, Bovet P, Bush AI, Conus P, Copolov D, Fornari E, Meuli R, Solida A, Vianin P, Cuénod M, Buclin T, Do KQ (Aug 2008). "Glutathione precursor, N-acetyl-cysteine, improves mismatch negativity in schizophrenia patients". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (9): 2187–99. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301624. PMID 18004285.

^ Dodd S, Dean O, Copolov DL, Malhi GS, Berk M (Dec 2008). "N-acetylcysteine for antioxidant therapy: pharmacology and clinical utility". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 8 (12): 1955–62. doi:10.1517/14728220802517901. PMID 18990082.

^ Kupchik YM, Moussawi K, Tang XC, Wang X, Kalivas BC, Kolokithas R, Ogburn KB, Kalivas PW (Jun 2012). "The effect of N-acetylcysteine in the nucleus accumbens on neurotransmission and relapse to cocaine". Biological Psychiatry. 71 (11): 978–86. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.024. PMC 3340445. PMID 22137594.

^ "N-Acetyl-L-cysteine | C5H9NO3S - PubChem". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

^ ab Head, Stewart I. (2017-10-29). "Antioxidant therapy in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: some promising results but with a weighty caveat". The Journal of Physiology. 595 (23): 7015–7015. doi:10.1113/jp275232. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 5709324. PMID 29034480.

^ Gu F, Chauhan V, Chauhan A (Jan 2015). "Glutathione redox imbalance in brain disorders". Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 18 (1): 89–95. doi:10.1097/MCO.0000000000000134. PMID 25405315.

^ Hoffer ME, Balaban C, Slade MD, Tsao JW, Hoffer B (2013). "Amelioration of acute sequelae of blast induced mild traumatic brain injury by N-acetyl cysteine: a double-blind, placebo controlled study". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e54163. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054163. PMC 3553161. PMID 23372680.

^ Bachert C, Hörmann K, Mösges R, Rasp G, Riechelmann H, Müller R, Luckhaupt H, Stuck BA, Rudack C (Mar 2003). "An update on the diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis and nasal polyposis". Allergy. 58 (3): 176–91. doi:10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.02172.x. PMID 12653791.

^ Fulghesu AM, Ciampelli M, Muzj G, Belosi C, Selvaggi L, Ayala GF, Lanzone A (Jun 2002). "N-acetyl-cysteine treatment improves insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertility and Sterility. 77 (6): 1128–35. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03133-3. PMID 12057717.

^ Aitio ML (Jan 2006). "N-acetylcysteine -- passe-partout or much ado about nothing?". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 61 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02523.x. PMC 1884975. PMID 16390346.

^ Williamson J, Doig WM, Forrester JV, Tham MH, Wilson T, Whaley K, Dick WC (Sep 1974). "Management of the dry eye in Sjogren's syndrome". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 58 (9): 798–805. doi:10.1136/bjo.58.9.798. PMC 1215027. PMID 4433493.

^ Edwards MJ, Hargreaves IP, Heales SJ, Jones SJ, Ramachandran V, Bhatia KP, Sisodiya S (Nov 2002). "N-acetylcysteine and Unverricht-Lundborg disease: variable response and possible side effects". Neurology. 59 (9): 1447–9. doi:10.1212/wnl.59.9.1447. PMID 12427904.

^ Ataxia with Identified Genetic and Biochemical Defects at eMedicine

^ "Use of NAC in Alleviation of Hangover Symptoms - Study Results - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov.

External links

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Acetylcysteine