Missouri Compromise

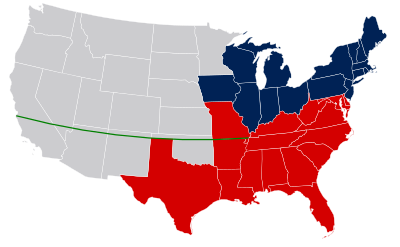

The United States in 1819, The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the unorganized territory of the Great Plains (upper dark green) and permitted it in Missouri (yellow) and the Arkansas Territory (lower blue area)

|

The Missouri Compromise was the legislation that provided for the admission of Maine to the United States as a free state along with Missouri as a slave state, thus maintaining the balance of power between North and South in the United States Senate. As part of the compromise, slavery was prohibited north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.[1]

Earlier, on February 4, 1820, Representative James Tallmadge Jr., a Jeffersonian Republican from New York, submitted two amendments to Missouri's request for statehood, which included restrictions on slavery. Southerners objected to any bill which imposed federal restrictions on slavery, believing that slavery was a state issue settled by the Constitution. However, with the Senate evenly split at the opening of the debates, both sections possessing 11 states, the admission of Missouri as a slave state would give the South an advantage. Northern critics including Federalists and Democratic-Republicans objected to the expansion of slavery into the Louisiana Purchase territory on the Constitutional inequalities of the three-fifths rule, which conferred Southern representation in the federal government derived from a states' slave population. Jeffersonian Republicans in the North ardently maintained that a strict interpretation of the Constitution required that Congress act to limit the spread of slavery on egalitarian grounds. "[Northern] Republicans rooted their antislavery arguments, not on expediency, but in egalitarian morality";[2] and "The Constitution, [said northern Jeffersonians] strictly interpreted, gave the sons of the founding generation the legal tools to hasten [the] removal [of slavery], including the refusal to admit additional slave states.".[3]

When free-soil Maine offered its petition for statehood, the Senate quickly linked the Maine and Missouri bills, making Maine admission a condition for Missouri entering the Union with slavery unrestricted. Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois added a compromise proviso, excluding slavery from all remaining lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36° 30' parallel. The combined measures passed the Senate, only to be voted down in the House by those Northern representatives who held out for a free Missouri. Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky, in a desperate bid to break the deadlock, divided the Senate bills. Clay and his pro-compromise allies succeeded in pressuring half the anti-restrictionist House Southerners to submit to the passage of the Thomas proviso, while maneuvering a number of restrictionist House northerners to acquiesce in supporting Missouri as a slave state.[4][5] The Missouri question in the 15th Congress ended in stalemate on March 4, 1819, the House sustaining its northern antislavery position, and the Senate blocking a slavery restricted statehood.

The Missouri Compromise was controversial at the time, as many worried that the country had become lawfully divided along sectional lines. The bill was effectively repealed in the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, and declared unconstitutional in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). This increased tensions over slavery and eventually led to the Civil War.

Contents

1 The Era of Good Feelings and party "amalgamation"

2 The Louisiana Purchase and Missouri Territory

3 The 15th Congress Debates: 1819

3.1 Jeffersonian Republicanism and slavery

4 Struggle for political power

4.1 "Federal Ratio" in the House

4.2 "Balance of Power" in the Senate

4.3 Constitutional arguments

5 Stalemate

6 Federalist "plots" and "consolidation"

7 Development in Congress

7.1 Second Missouri Compromise

8 Impact on political discourse

9 Repeal

10 See also

11 References

12 Bibliography

13 Further reading

14 External links

The Era of Good Feelings and party "amalgamation"

President James Monroe: signer of the Missouri Compromise bills[6]

The Era of Good Feelings, closely associated with the administration of President James Monroe (1817–1825), was characterized by the dissolution of national political identities.[7][8] With the discredited Federalists in decline nationally, the "amalgamated" or hybridized Republicans adopted key Federalist economic programs and institutions, further erasing party identities and consolidating their victory.[9][10]

The economic nationalism of the Era of Good Feelings that would authorize the Tariff of 1816 and incorporate the Second Bank of the United States portended an abandonment of the Jeffersonian political formula for strict construction of the constitution, a limited central government and commitments to the primacy of Southern agrarian interests.[11][12] The end of opposition parties also meant the end of party discipline and the means to suppress internecine factional animosities. Rather than produce political harmony, as President James Monroe had hoped, amalgamation had led to intense rivalries among Jeffersonian Republicans.[13]

It was amid the "good feelings" of this period – during which Republican Party discipline was in abeyance – that the Tallmadge Amendment surfaced.[14]

The Louisiana Purchase and Missouri Territory

The immense Louisiana Purchase territories had been acquired through federal executive action, followed by Republican legislative authorization in 1803 during the Thomas Jefferson administration.[15]

Prior to its purchase in 1803, the governments of Spain and France had sanctioned slavery in the region. In 1812, the state of Louisiana, a major cotton producer and the first to be carved from the Louisiana Purchase, had entered the Union as a slave state. Predictably, Missourians were adamant that slave labor should not be molested by the federal government.[16] In the years following the War of 1812, the region, now known as Missouri Territory, experienced rapid settlement, led by slaveholding planters.[17]

Agriculturally, the land comprising the lower reaches of the Missouri River, from which that new state would be formed, had no prospects as a major cotton producer. Suited for diversified farming, the only crop regarded as promising for slave labor was hemp culture. On that basis, southern planters immigrated with their chattel to Missouri, the slave population rising from 3,100 in 1810 to 10,000 in 1820. In a total population 67,000, slaves represented about 15 percent.[18]

By 1818, the population of Missouri territory was approaching the threshold that would qualify it for statehood. An enabling act was provided to Congress empowering territorial residents to select convention delegates and draft a state constitution.[19] The admission of Missouri territory as a slave state was expected to be more or less routine.[20][21]

The 15th Congress Debates: 1819

Representative James Tallmadge Jr., author of the antislavery amendment to Missouri statehood

When the Missouri statehood bill was opened for debate in the House of Representative on February 13, 1819, early exchanges on the floor proceeded without serious incident.[22] In the course of these proceedings, however, Representative James Tallmadge Jr. of New York "tossed a bombshell into the Era of Good Feelings" with the following amendments:[23]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Provided, that the further introduction of slavery or involuntary servitude be prohibited, except for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been fully convicted; and that all children born within the said State will be executed after the admission thereof into the Union, shall be free at the age of twenty-five years.[24]

A political outsider, the 41-year old Tallmadge conceived his amendment based on a personal aversion to slavery. He had played a leading role in accelerating emancipation of the remaining slaves in New York in 1817. Moreover, he had campaigned against Illinois' Black Codes: though ostensibly free-soil, the new Illinois state constitution permitted indentured servitude and a limited form of slavery.[25][26] As a New York Republican, Tallmadge maintained an uneasy association with Governor DeWitt Clinton, a former Republican who depended on support from ex-Federalists. Clinton's faction was hostile to Tallmadge for his spirited defense of General Andrew Jackson over his contentious invasion of Florida.[27][28]

Tallmadge had to back from a fellow New York Republican, Congressman John W. Taylor (not to be confused with legislator John Taylor of Caroline County, Virginia). Taylor also had antislavery credentials: In February 1819, he had proposed similar slave restrictions on Arkansas territory in the House, but failed 89-87. He would lead the pro-Tallmadge antislavery forces during the 16th Congress in 1820.[29]

The amendment instantly exposed the polarization among Jeffersonian Republicans over the future of slavery in the nation.[30][31]

Northern Jeffersonian Republicans formed a coalition across factional lines with remnants of the Federalists. Southern Jeffersonian united in almost unanimous opposition. The ensuing debates pitted the northern "restrictionists" (antislavery legislators who wished to bar slavery from the Louisiana territories) and southern "anti-restrictionists" (proslavery legislators who rejected any interference by Congress inhibiting slavery expansion).[32]

The sectional "rupture" over slavery among Jeffersonian Republicans, first exposed in the Missouri crisis, had its roots in the Revolutionary generation.[33]

Five Congressmen in Maine were opposed to spreading slavery into new territories. Dr. Brian Purnell, professor of Africana Studies and U.S. history at Bowdoin College, writes in Portland Magazine, "Martin Kinsley, Joshua Cushman, Ezekiel Whitman, Enoch Lincoln, and James Parker—wanted to prohibit slavery's spread into new territories. In 1820, they voted against the Missouri Compromise and against Maine's independence. In their defense, they wrote that, if the North, and the nation, embarked upon this Compromise—and ignored what experiences proved, namely that southern slave holders were determined to dominate the nation through ironclad unity and perpetual pressure to demand more land, and more slaves—then these five Mainers declared Americans "shall deserve to be considered a besotted and stupid race, fit, only, to be led blindfold; and worthy, only, to be treated with sovereign contempt."[34]

Jeffersonian Republicanism and slavery

Thomas Jefferson: The Missouri crisis roused Jefferson "like a fire bell in the night."[35]

The Missouri crisis marked a rupture in the Republican Ascendency – the national association of Jeffersonian Republicans that dominated national politics in the post-War of 1812 period.[36]

The Founders had inserted both principled and expedient elements in the establishing documents. The Declaration of Independence of 1776 was grounded on the claim that liberty established a moral ideal that made universal equality a common right.[37] The Revolutionary War generation had formed a government of limited powers in 1787 to embody the principles in the Declaration, but "burdened with the one legacy that defied the principles of 1776": human bondage.[38] In a pragmatic commitment to form the Union, the federal apparatus would forego any authority to directly interfere with the institution of slavery where it existed under local control within the states. This acknowledgment of state sovereignty provided for the participation of those states most committed to slave labor. With this understanding, slaveholders had cooperated in authorizing the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, and to outlawing the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1808.[39] Though the Founders sanctioned slavery, they did so with the implicit understanding that the slaveholding states would take steps to relinquish the institution as opportunities arose.[40]

Southern states, after the War for Independence, had regarded slavery as an institution in decline (with the exception of Georgia and South Carolina). This was manifest in the shift towards diversified farming in the Upper South, and in the gradual emancipation of slaves in New England, and more significantly, in the mid-Atlantic states. Beginning in the 1790s, with the introduction of the cotton gin, and by 1815, with the vast increase in demand for cotton internationally, slave-based agriculture underwent an immense revival, spreading the institution westward to the Mississippi River. Slavery opponents in the South vacillated, as did their hopes for the imminent demise of human bondage.[41]

However rancorous the disputes among Southerners themselves over the virtues of a slave-based society, they united as a section when confronted by external challenges to their institution. The free states were not to meddle in the affairs of the slaveholders. Southern leaders – of whom virtually all identified as Jeffersonian Republicans – denied that Northerners had any business encroaching on matters related to slavery. Northern attacks on the institution were condemned as incitements to riot among the slave populations – deemed a dire threat to white southern security.[42][43]

Northern Jeffersonian Republicans embraced the Jeffersonian antislavery legacy during the Missouri debates, explicitly citing the Declaration of Independence as an argument against expanding the institution. Southern leaders, seeking to defend slavery, would renounce the document's universal egalitarian applications and its declaration that "all men are created equal."[44]

Struggle for political power

"Federal Ratio" in the House

Rufus King: last of the Federalist icons

Article One, Section Two of the US Constitution supplemented legislative representation in those states where residents owned slaves. Known as the three-fifths clause or the "federal ratio", three-fifths (60%) of the slave population was numerically added to the free population. This sum was used to calculate Congressional districts per state and the number of delegates to the Electoral College. The federal ratio produced a significant number of legislative victories for the South in the years preceding the Missouri crisis, as well as augmenting its influence in party caucuses, the appointment of judges and the distribution of patronage. It is unlikely that the three-fifths clause, prior to 1820, was decisive in affecting legislation on slavery. Indeed, with the rising northern representation in the House, the South's share of the membership had declined since the 1790s.[45][46]

Hostility to the federal ratio had historically been the object of the now nationally ineffectual Federalists; they blamed their collective decline on the "Virginia Dynasty", expressed in partisan terms rather than in moral condemnation of slavery. The pro-De Witt Clinton-Federalist faction carried on the tradition, posing as antirestrictionists, for the purpose of advancing their fortunes in New York politics.[47][48]

Senator Rufus King of New York, a Clinton associate, was the last Federalist icon still active on the national stage, a fact irksome to Southern Republicans.[49] A signatory to the US Constitution, he had strongly opposed the three-fifths rule in 1787. In the 1819 15th Congress debates, he revived his critique as a complaint that New England and the Mid-Atlantic States suffered unduly from the federal ratio, declaring himself "degraded" (politically inferior) to the slaveholders. Federalists, North and South, preferred to mute antislavery rhetoric, but during the 1820 debates in the 16th Congress, King and other old Federalists would expand their critique to include moral considerations of slavery.[50][51]

Republican James Tallmadge, Jr. and the Missouri restrictionists deplored the three-fifths clause because it had translated into political supremacy for the South. They had no agenda to remove it from the founding document, only to prevent its further application west of the Mississippi River.[52][53]

As determined as Southern Republicans were to secure Missouri statehood with slavery, the three-fifths clause failed to provide the margin of victory in the 15th Congress. Blocked by Northern Republicans – largely on egalitarian grounds – with sectional support from Federalists, the bill would die in the upper house, where the federal ratio had no relevance. The "balance of power" between the sections, and the maintenance of Southern preeminence on matters related to slavery resided in the Senate.[54][55]

"Balance of Power" in the Senate

Northern voting majorities in the lower house did not translate into political dominance. The fulcrum for proslavery forces resided in the upper house of Congress. There, constitutional compromise in 1787 had provided for exactly two senators per state, regardless of its population: the South, with its small white demographic relative to the North, benefited from this arrangement. Since 1815, sectional parity in the Senate had been achieved through paired admissions, leaving the North and South, at the time of Missouri territory application for statehood, at eleven states each.[56]

The South, voting as a bloc on measures that challenged slaveholding interests and augmented by defections from Free State Senators with Southern sympathies, was able to tally majorities. The Senate stood as the bulwark and source of the Slave Power – a power that required admission of slave states to the Union to preserve its national primacy.[57][58]

Missouri statehood, with the Tallmadge amendment approved, would set a trajectory towards a Free State trans-Mississippi and a decline in Southern political authority. The question as to whether the Congress could lawfully restrain the growth of slavery in Missouri took on great importance among the slave states. The moral dimensions of the expansion of human bondage would be raised by Northern Republicans on constitutional grounds.[59][60]

Constitutional arguments

The Tallmadge amendment was "the first serious challenge to the extension of slavery" and raised questions concerning the interpretation of the republics' founding documents.[61]

Jeffersonian Republicans justified Tallmadge's slavery restrictions on the grounds that Congress possessed the authority to impose territorial statutes which would remain in force after statehood was established. Representative John W. Taylor pointed to Indiana and Illinois, where their Free State status conformed to the antislavery provisions in the Northwest Ordinance.

[62]

Massachusetts Representative Timothy Fuller

Further, antislavery legislators invoked Article Four, Section Four of the Constitution, which required that states provide a republican form of government. As the Louisiana Territory was not part of the United States in 1787, they argued, introducing slavery into Missouri would thwart the egalitarian intent of the Founders.[63][64]

Proslavery Republicans countered that the Constitution had long been interpreted as having relinquished any claim to restricting slavery within the states. The free inhabitants of Missouri, either in the territorial phase or during statehood, had the right to establish slavery – or disestablish it – exclusive of central government interference. As to the Northwest Ordinance, Southerners denied that this could serve as a lawful antecedent for the territories of the Louisiana Purchase, as the ordinance had been issued originally under the Articles of Confederation, not under the US Constitution.[65]

As a legal precedent, they offered the treaty acquiring the Louisiana lands in 1803: the document included a provision (Article 3) that extended the rights of US citizens to all inhabitants of the new territory, including the protection of property in slaves.[65] When slaveholders embraced Jeffersonian constitutional strictures on a limited central government they were reminded that Jefferson, as US President in 1803, had deviated from these precepts when he wielded federal executive power to double the size the United States (including the lands under consideration for Missouri statehood). In doing so, he set a Constitutional precedent that would serve to rationalize Tallmadge's federally imposed slavery restrictions.[66]

The 15th Congress debates, focusing as it did on constitutional questions, largely avoided the moral dimensions raised by the topic of slavery. That the unmentionable subject had been raised publicly was deeply offensive to Southern Congressmen, and violated the long-held sectional understanding between free and slave state legislators.[67]

Missouri statehood confronted Southern Jeffersonians with the prospect of applying the egalitarian principles espoused by the Revolutionary generation. This would require halting the spread of slavery westward, and confine the institution to where it already existed. Faced with a population of 1.5 million slaves, and the lucrative production of cotton, the South would abandon hopes for containment. Slaveholders in the 16th Congress, in an effort to come to grips with this paradox, would resort to a theory that called for extending slavery geographically so as to encourage its decline: "diffusion".[68][69]

Stalemate

On February 16, 1819, the House Committee of the Whole voted to link Tallmadge's provisions with the Missouri enabling legislation, approving the move 79-67.[70][71] Following the committee vote, debates resumed over the merits of each of Tallmadge's provisions in the enabling act. The debates in the House's 2nd session in 1819 lasted only three days. They have been characterized as "rancorous", "fiery", "bitter", "blistering", "furious" and "bloodthirsty".[72]

You have kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish.

— Representative Thomas W. Cobb of Georgia

If a dissolution of the Union must take place, let it be so! If civil war, which gentlemen so much threaten, must come, I can only say, let it come!

— Representative James Tallmadge Jr. of New York:

Northern representatives outnumbered the South in House membership 105 to 81. When each of the restrictionist provisions were put to the vote, they passed along sectional lines: 87 to 76 in favor of prohibition on further slave migration into Missouri (Table 1) and 82 to 78 in favor of emancipating slave offspring at age twenty-five.[73][74]

| Table 1. House vote on restricting slavery in Missouri. 15th Congress 2nd Session, February 16, 1819. | Yea* | Nay | Abst | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Northern Federalists | 22 | 3 | 3 | 28 |

Northern Republicans | 64 | 7 | 7 | 77 |

North Total | 86 | 10 | 9 | 105 |

South Total | 1 | 66 | 13 | 80 |

| House Total | 87 | 76 | 22 | 185 |

| *Yea is an antislavery (restrictionist) vote |

The enabling bill was passed to the Senate, where both parts of it were rejected: 22 to 16 opposed to restricting new slaves in Missouri (supported by five northerners, two of whom were the proslavery legislators from the free state of Illinois); and 31 to 7 against gradual emancipation for slave children born post-statehood.[75] House antislavery restrictionists refused to concur with the Senate proslavery anti-restrictionists: Missouri statehood would devolve upon the 16th Congress in December 1819.[76][77]

Federalist "plots" and "consolidation"

New York Governor DeWitt Clinton

The Missouri Compromise debates stirred suspicions among proslavery interests that the underlying purpose of the Tallmadge amendments had little to do with opposition to slavery expansion.

The accusation was first leveled in the House by the Republican anti-restrictionist John Holmes from the District of Maine. He suggested that Senator Rufus King's "warm" support for the Tallmadge amendment concealed a conspiracy to organize a new antislavery party in the North – a party composed of old Federalists in combination with disaffected antislavery Republicans. The fact that King, in the Senate, and Tallmadge and Tyler, in the House – all New Yorkers – were among the vanguard for slavery restriction in Missouri lent credibility to these charges. When King was re-elected to the US Senate in January 1820, during the 16th Congress debates, and with bipartisan support, suspicions deepened and would persist throughout the crisis.[78][79] Southern Jeffersonian Republican leadership, including President Monroe and former President Thomas Jefferson, considered it as an article of faith that Federalists, given the chance, would destabilize the Union so as to re-impose monarchal rule in North America, and "consolidate" political control over the people by expanding the functions of the central government. Jefferson, at first unperturbed by the Missouri question, soon became convinced that a northern conspiracy was afoot, with Federalists and crypto-Federalists posing as Republicans, using Missouri statehood as a pretext.[80]

Due to the disarray of the Republican Ascendency brought about by amalgamation, fears abounded among Southerners that a Free State party might take shape in the event that Congress failed to reach an understanding over Missouri and slavery: Such a party would threaten Southern preeminence. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts surmised that the political configuration for just such a sectional party already existed.[81][82]

That the Federalists were anxious to regain a measure of political participation in national politics is indisputable. There was no basis, however, for the charge that Federalists had directed Tallmadge in his antislavery measures, nor was there anything to indicate that a New York-based King-Clinton alliance sought to erect an antislavery party on the ruins of the Republican Party. The allegations by Southern proslavery interests of a "plot" or that of "consolidation" as a threat to the Union misapprehended the forces at work in the Missouri crisis: the core of the opposition to slavery in the Louisiana Purchase were informed by Jeffersonian egalitarian principles, not a Federalist resurgence.[83][84]

Development in Congress

Extension of the Missouri Compromise Line westward was discussed by Congress during the Texas Annexation in 1845, during the Compromise of 1850, and as part of the proposed Crittenden Compromise in 1860, but the line never reached the Pacific.

To balance the number of "slave states" and "free states", the northern region of what was then Massachusetts, the District of Maine, ultimately gained admission into the United States as a free state to become Maine. This only occurred as a result of a compromise involving slavery in Missouri, and in the federal territories of the American West.[85]

The admission of another slave state would increase the South's power at a time when northern politicians had already begun to regret the Constitution's Three-Fifths Compromise. Although more than 60 percent of whites in the United States lived in the North, by 1818 northern representatives held only a slim majority of congressional seats. The additional political representation allotted to the South as a result of the Three-Fifths Compromise gave southerners more seats in the House of Representatives than they would have had if the number was based on just free population. Moreover, since each state had two Senate seats, Missouri's admission as a slave state would result in more southern than northern senators.[86] A bill to enable the people of the Missouri Territory to draft a constitution and form a government preliminary to admission into the Union came before the House of Representatives in Committee of the Whole, on February 13, 1819. James Tallmadge of New York offered an amendment, named the Tallmadge Amendment, that forbade further introduction of slaves into Missouri, and mandated that all children of slave parents born in the state after its admission should be free at the age of 25. The committee adopted the measure and incorporated it into the bill as finally passed on February 17, 1819, by the house. The United States Senate refused to concur with the amendment, and the whole measure was lost.[87][88]

During the following session (1819–1820), the House passed a similar bill with an amendment, introduced on January 26, 1820, by John W. Taylor of New York, allowing Missouri into the union as a slave state. The question had been complicated by the admission in December of Alabama, a slave state, making the number of slave and free states equal. In addition, there was a bill in passage through the House (January 3, 1820) to admit Maine as a free state.[89]

The Senate decided to connect the two measures. It passed a bill for the admission of Maine with an amendment enabling the people of Missouri to form a state constitution. Before the bill was returned to the House, a second amendment was adopted on the motion of Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois, excluding slavery from the Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north (the southern boundary of Missouri), except within the limits of the proposed state of Missouri.[90]

The vote in the Senate was 24 for the compromise, to 20 against. The amendment and the bill passed in the Senate on February 17 and February 18, 1820. The House then approved the Senate compromise amendment, on a vote of 90 to 87, with those 87 votes coming from free state representatives opposed to slavery in the new state of Missouri.[90] The House then approved the whole bill, 134 to 42, with opposition from the southern states.[90]

Second Missouri Compromise

The two houses were at odds not only on the issue of the legality of slavery but also on the parliamentary question of the inclusion of Maine and Missouri within the same bill. The committee recommended the enactment of two laws, one for the admission of Maine, the other an enabling act for Missouri. They recommended against having restrictions on slavery but for including the Thomas amendment. Both houses agreed, and the measures were passed on March 5, 1820, and were signed by President James Monroe on March 6.

The question of the final admission of Missouri came up during the session of 1820–1821. The struggle was revived over a clause in Missouri's new constitution (written in 1820) requiring the exclusion of "free negroes and mulattoes" from the state. Through the influence of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay "The Great Compromiser", an act of admission was finally passed, upon the condition that the exclusionary clause of the Missouri constitution should "never be construed to authorize the passage of any law" impairing the privileges and immunities of any U.S. citizen. This deliberately ambiguous provision is sometimes known as the Second Missouri Compromise.[91]

Impact on political discourse

During the decades following 1820, Americans hailed the 1820 agreement as an essential compromise almost on the sacred level of the Constitution itself.[92] Although the Civil War broke out in 1861, historians often say the Compromise helped postpone the war.[93]

Animation showing the free/slave status of U.S. states and territories, 1789–1861, including the Missouri Compromise

These disputes involved the competition between the southern and northern states for power in Congress and for control over future territories. There were also the same factions emerging as the Democratic-Republican party began to lose its coherence. In an April 22 letter to John Holmes, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the division of the country created by the Compromise Line would eventually lead to the destruction of the Union:[94]

... but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.[95][96]

The debate over admission of Missouri also raised the issue of sectional balance, for the country was equally divided between slave and free states with eleven each. To admit Missouri as a slave state would tip the balance in the Senate (made up of two senators per state) in favor of the slave states. For this reason, northern states wanted Maine admitted as a free state. Maine was admitted in 1820[97] and Missouri in 1821,[98] but no further states were added until 1836, when Arkansas was admitted.[99]

From the constitutional standpoint, the Compromise of 1820 was important as the example of Congressional exclusion of slavery from U.S. territory acquired since the Northwest Ordinance. Nevertheless, the Compromise was deeply disappointing to African-Americans in both the North and South, as it stopped the southern progression of gradual emancipation at Missouri's southern border and legitimized slavery as a southern institution.[100]

Repeal

The provisions of the Missouri Compromise forbidding slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north were effectively repealed by Stephen A. Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. The repeal of the Compromise caused outrage in the North and sparked the return to politics of Abraham Lincoln,[101] who criticized slavery and excoriated Douglas's act in his "Peoria Speech" (October 16, 1854).[102]

See also

- Compromise of 1790

- Compromise of 1850

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Royal Colonial Boundary of 1665

- Tallmadge Amendment

- Slave Trade Acts

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- Northwest Ordinance

References

^ Dangerfield, 1966. p. 125

Wilentz, 2004. p. 382

^ Wilentz 2004. p. 387

^ Wilentz 2004 p. 389

^ Brown, 1966. p. 25: "[Henry Clay], who managed to bring up the separate parts of the compromise separately in the House, enabling the Old Republicans [in the South] to provide him with a margin of victory on the closely contested Missouri [statehood] bill while saved their pride by voting against the Thomas Proviso."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 381

^ Ammons, 1971. p. 457-458

^ Ammon, 1958, p. 4: "The phrase 'Era of Good Feelings', so inextricably associated with the administration of James Monroe ...

^ Brown, 1966. p. 23: "So long as the Federalists remained an effective opposition, Jefferson's party worked as a party should. It maintained its identity in relation to the opposition by a moderate and pragmatic advocacy of strict construction of the Constitution. Because it had competition, it could maintain discipline. It responded to its constituent elements because it depended on them for support. But eventually, its very success was its undoing. After 1815, stirred by the nationalism of the postwar era, and with the Federals in decline, the Republicans took up Federalist positions on a number of the great public issues of the day, sweeping all before then as they did. The Federalists gave up the ghost. In the Era of Good Feelings which followed, everybody began to call himself a Republican, and a new theory of party amalgamation preached the doctrine that party division was bad and that a one-party system best served the national interest. Only gradually did it become apparent that in victory the Republicans party had lost its identity – and it's usefulness. As the party of the whole nation, it ceased to be responsive to any particular elements in its constituency. It ceased to be responsive to the North ... When it did [become unresponsive], and because it did, it invited the Missouri crisis of 1819–1820 ..."

^ Ammon, 1958, p. 5: "Most Republicans like former President [James] Madison readily acknowledged the shift that had taken place within the Republican party towards Federalist principles and viewed the process without qualms. And p. 4: "... The Republicans had taken over (as they saw it) that which was of permanent value in the Federal program." And p. 10: "... Federalists had vanished" from national politics.

^ Brown, 1966, p. 23: "... a new theory of party amalgamation preached the doctrine that party division was bad and that a one-party system best served the national interest" and "After 1815, stirred by the nationalism of the post-war era, and with the Federalists in decline, the Republicans took up the Federalist positions on a number of the great public issues of the day, sweeping all before them as they did. The Federalists gave up the ghost."

^ Brown, 1966, p. 22: "The insistence(FILL) ... outside the South" and p. 23: The amalgamated Republicans, "as a party of the whole nation ... ceased to be responsive to any particular elements in its constituency. It ceased to be responsive to the South." And "The insistence that slavery was uniquely a Southern concern, not to be touched by outsiders, had been from the outset a sine qua non for Southern participation in national politics. It underlay the Constitution and its creation of a government of limited powers ..."

Brown, 1966, p. 24: "Not only did the Missouri crisis make these matters clear [the need to revive strict constructionist principles and quiet anti-slavery agitation], but "it gave marked impetus to a reaction against nationalism and amalgamation of postwar Republicanism" and the rise of the Old Republicans.

^ Ammon, 1971 (James Monroe bio) p. 463: "The problems presented by the [consequences of promoting Federalist economic nationalism] gave an opportunity to the older, more conservative [Old] Republicans to reassert themselves by attributing the economic dislocation to a departure from the principles of the Jeffersonian era."

^ Parsons, 2009, p. 56: "Animosity between Federalists and Republicans had been replaced by animosity between Republicans themselves, often over the same issues that had once separated them from the Federalists."

^ Brown, 1966, p.28: "... amalgamation had destroyed the levers which made party discipline possible."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 36

Ammons, 1971. p. 206

Ellis, 1996. p. 266: "Jefferson had in fact worried out loud that the constitutional precedent he was setting with the acquisition of Louisiana in 1803. In that sense his worries proved to be warranted. The entire congressional debate of 1819–1820 over the Missouri Question turned on the question of federal versus state sovereignty, essentially a constitutional conflict in which Jefferson's long-standing opposition to federal power was clear and unequivocal, the Louisiana Purchase being the one exception that was now coming back to haunt him. But just as the constitutional character of the congressional debate served only to mask the deeper moral and ideological issues at stake, Jefferson's own sense of regret at his complicity in providing the constitutional precedent for the Tallmadge amendment merely scratched that surface of his despair."

^ Malone, 1960. p. 419: "[S]everal thousand planters took their slaves into the area believing that Congress would do nothing to disturb the institution, which had enjoyed legal protection in the territory of the Louisiana Purchase under its former French and Spanish rulers."

^ Malone, 1969. p.419: "After 1815, settlers had poured across the Mississippi ... Several thousand planters took their slaves in the area ..."

^ Dangerfield, 1966. p. 109

Wilentz, 2004. P. 379: "Missouri, unlike Louisiana, was not suited to cotton, but slavery had been established in the western portions, which were especially promising for growing hemp, a crop so taxing to cultivate that it was deemed fit only for slave labor. Southerners worried that a ban on slavery in Missouri, already home to 10,000 slaves – roughly fifteen percent of its total population [85% whites] – would create a precedent for doing so in all the entering states from the trans-Mississippi West, thereby establishing congressional powers that slaveholders denied existed

^ Howe, 2004, p. 147: "By 1819, enough settlers had crossed the Mississippi River that Missouri Territory could meet the usual population criterion for admission to the Union." And "an 'enabling act' was presented to Congress [for Missouri statehood]."

Malone, 1960. p. 419: "[S]ettlement had reached the point where Missouri, the next state [after Louisiana state] to be carved out of the Louisiana Purchase, straddled the line between the free and slave states."

^ Ammons, 1971. p. 449: "Certainly no one guessed in February 1819 the extent to which passions would be stirred by the introduction of a bill to permit Missouri to organize a state government."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 379: "When the territorial residents of Missouri applied for admission to the Union, most Southerners—and, probably, at first, most Northerners—assumed slavery would be allowed. All were in for a shock."

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 107: Prior to the Tallmadge debates, the 15th Congress there had been "certain arguments or warnings concerning congressional powers in the territories; none the less ... [Tallmadge's amendment] caught the House off its guard."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 106-107

^ Howe, 2004. p. 147

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 107

^ Dangerfield, 1965, p. 110: "When Tallmadge, in 1818, attacked the indentured service and limited slavery provisions in the Illinois constitution, only thirty-four representatives voted with him against admission. The Tallmadge amendment of 1819, therefore, must also be considered the first serious challenge to the extension of slavery.

^ Howe, 2004. p. 147: "Tallmadge was an independent-minded Republican, allied at the time with Dewitt Clinton's faction in New York state politics. The year before, he had objected to the admission of Illinois on the (well-founded) grounds that its constitution did not provide enough assurance that the Northwest Ordinance prohibition on slavery would be perpetuated."

Wilentz, 2004. p. 379: "In 1818, when Illinois gained admission to the Union, antislavery forces won a state constitution that formally barred slavery but included a fierce legal code that regulated free blacks and permitted the election of two Southern-born senators."

^ Howe 2010

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 378: "A Poughkeepsie lawyer and former secretary to Governor George Clinton, Tallmadge had served in Congress for just over two years when he made his brief but momentous appearance in national politics. He was known as a political odd duck. Nominally an ally and kin, by marriage, of De Witt Clinton, who nonetheless distrusted him, Tallmadge was disliked by the surviving New York Federalists, who detested his defense of General Andrew Jackson against attacks on Jackson's military command in East Florida.

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 107-108: "James Tallmadge, Jr. a representative [of New York state] ... was supposed to be a member of the [DeWitt Clinton] faction in New York politics ... may have offered his amendment because his conscience was affronted, and for no other reason.

^ Dangerfield, 1965: p. 107, footnote 28: In February 1819,[Taylor, attempted] to insert into a bill establishing a Territory of Arkansas an antislavery clause similar to [the one Tallmadge would shortly present] ... and it "was defeated in the House 89-87."

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 122

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 376: "[T]he sectional divisions among the Jeffersonian Republicans ... offers historical paradoxes ... in which hard-line slaveholding Southern Republicans rejected the egalitarian ideals of the slaveholder [Thomas] Jefferson while the antislavery Northern Republicans upheld them – even as Jefferson himself supported slavery's expansion on purportedly antislavery grounds.

^ Dangerfleld, 1965. p. 111: "The most prominent feature of the voting at this stage was its apparently sectional character."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p.380,386

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 376: "Jeffersonian rupture over slavery drew upon ideas from the Revolutionary era. It began with congressional conflicts over slavery and related matter in the 1790s. It reached a crisis during the first great American debate about slavery in the nineteenth century, over the admission of Missouri to the Union."

^ Portland Magazine, September 2018

^ Wilentz, 2004 p. 376: "When fully understood, however, the story of sectional divisions among the Jeffersonians recovers the Jeffersonian antislavery legacy, exposes the fragility of the "second party system" of the 1830s and 1840s, and vindicates Lincoln's claims about his party's Jeffersonian origins. The story also offers historical paradoxes of its own, in which hardline slaveholding Southern Republicans rejected the egalitarian ideals of the slave-holder Jefferson while anti-slavery Northern Republicans upheld them—even as Jefferson himself supported slavery's expansion on purportedly antislavery grounds. The Jeffersonian rupture over slavery drew upon ideas from the Revolutionary era. It began with congressional conflicts over slavery and related matters in the 1790s. It reached a crisis during the first great American debate about slavery in the nineteenth century, over the admission of Missouri to the Union."

Ellis, 1995.p. 265, 269 and 271

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 376

^ Miller, 1995. p 16

^ Ellis 1995. p. 265: "[T]he idea of prohibiting the extension of slavery into the western territories could more readily be seen as a fulfillment rather than a repudiation of the American Revolution, indeed as the fulfillment of Jefferson's early vision of an expansive republic populated by independent farmers unburdened by the one legacy that defied the principles of 1776 [slavery]"

^ Brown, 1966. p. 22: "The insistence that slavery was uniquely a Southern concern, not to be touched by outsiders, had been from the outset a sine qua non for Southern participation in national politics. It underlay the Constitution and its creation of a government of limited powers, without which Southern participation would have been unthinkable."

^ Ellis, 1996. p. 267: "[The Founders' silence on slavery] was contingent upon some discernible measure of progress toward ending slavery."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 383: "Not since the framing and ratification of the Constitution in 1787–88 had slavery caused such a tempest in national politics. In part, the breakthrough of emancipation in the Middle States after 1789—especially in New York, where James Tallmadge played a direct role—emboldened Northern antislavery opinion. Southern slavery had spread since 1815. After the end of the War of 1812, and thanks to new demand from the Lancashire mills, the effects of Eli Whitney's cotton gin, and the new profitability of upland cotton, slavery expanded into Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Between 1815 and 1820, U.S. cotton production doubled, and, between 1820 and 1825, it doubled again. Slavery's revival weakened what had been, during the Revolutionary and post-Revolutionary era, a widespread assumption in the South, although not in South Carolina and Georgia, that slavery was doomed. By the early 1820s, Southern liberal blandishments of the post-Revolutionary years had either fallen on the defensive or disappeared entirely

^ Brown, 1966. p. 22: "... there ran one compelling idea that virtually united all Southerners, and which governed their participation in national politics. This was that the institution of slavery should not be dealt with from outside the South. Whatever the merits of the institution – and Southerners violently disagreed about this, never more so than in the 1820s – the presence of the slave was a fact too critical, too sensitive, too perilous to be dealt with by those not directly affected. Slavery must remain a Southern question."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 383: "Southerner leaders – of whom virtually all identified as Jeffersonian Republicans – denied that Northerners had any business encroaching on matters related to slavery. Northern attacks on the institution were regarded as incitements to riot among the slave populations – deemed a dire threat to white southern security. Tallmadge's amendments horrified Southern congressmen, the vast majority of whom were Jeffersonian Republicans. They claimed that whatever the rights and wrongs of slavery, Congress lacked the power to interfere with its expansion. Southerners of all factions and both parties rallied to the proposition that slavery must remain a Southern question.

^ Wilentz, 2004 p. 376: "When fully understood, however, the story of sectional divisions among the Jeffersonians recovers the Jeffersonian antislavery legacy, exposes the fragility of the "second party system" of the 1830s and 1840s, and vindicates Lincoln's claims about his party's Jeffersonian origins. The story also offers historical paradoxes of its own, in which hardline slaveholding Southern Republicans rejected the egalitarian ideals of the slave-holder Jefferson while anti-slavery Northern Republicans upheld them—even as Jefferson himself supported slavery's expansion on purportedly antislavery grounds. The Jeffersonian rupture over slavery drew upon ideas from the Revolutionary era. It began with congressional conflicts over slavery and related matters in the 1790s. It reached a crisis during the first great American debate about slavery in the nineteenth century, over the admission of Missouri to the Union."

^ Wilentz, 2016. p. 101: "The three-fifths clause certainly inflated Southerner's power in the House, not simply in affecting numerous roll-call votes – roughly one in three overall of those recorded between 1795 to 1821 – but in shaping the politics of party caucuses ... patronage and judicial appointments. Yet even with the extra seats, the share held by major slaveholding states actually declined between 1790 to 1820, from 45% to 42% ... [and] none of the bills listed in the study concerned slavery, whereas in 1819, antislavery Northerners, most of them Jeffersonian Republicans, rallied a clear House majority to halt slavery's expansion."

^ Varon, 2008. p. 40: "The three-fifths clause inflated the South's representation in the House. Because the number of presidential electors assigned to each state was equal to the size of its congressional delegation ... the South had power over the election of presidents that was disproportionate to the size of the region's free population ... since Jefferson's accession in 1801, a "Virginia Dynasty" had ruled the White House."

Malone, 1960. p. ?: "The constitutional provision relating to slavery that bore most directly on the [Missouri controversy] was the three-fifths ratio of representation, sometimes called the federal ratio. The representation of any state in the lower house of Congress was based on the number of its free inhabitants, push three-fifths of its slaves. The free states were now [1820] forging ahead in total population, were now had a definite majority. On the other hand, the delegation from the South was disproportionate to its free population, and the region actually had representation for its slave property. This situation vexed the Northerners, especially the New Englanders, who had suffered from political frustration since the Louisiana Purchase, and who especially resented the rule of the Virginia Dynasty."

Wilentz, 2016. p. 47: "[Federalists] objected above all to the increasingly notorious three-fifths clause [which] inflated representation of the Southern states in Congress and the Electoral College"

^ Wilentz, 2016. p. 99: "[Federalist hostility to Jefferson and the Virginia Dynasty] nothing about slavery or its cruelties showed up – except (in what had become a familiar sour-grapes excuse among Federalists for their national political failures) how the three-fifths clause aided the wretched ... Jeffersonians."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 109: "The federal ratio ... had hitherto been an object of the Federalist-Clintonian concern [rather than the Northern Jeffersonian Republicans]; whether the Republicans of the North and East would have gone to battle over Missouri is their hands had not been forced by Tallmadge's amendment is quite another question."

Howe, 2004, p. 150

Brown, 1966. p. 26

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 385

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 385: "More than thirty years after fighting the three-fifths clause at the Federal Convention, King warmly supported banning slavery in Missouri, restating the Yankee Federalist fear of Southern political dominance that had surfaced at the disgraced Hartford Convention in 1814. The issue, for King, at least in his early speeches on Missouri, was not chiefly moral. King explicitly abjured wanting to benefit either slaves or free blacks. His goal, rather, was to ward off the political subjugation of the older northeastern states—and to protect what he called 'the common defense, the general welfare, and [the] wise administration of government.' Only later did King and other Federalists begin pursuing broader moral and constitutional indictments of slavery.

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 121, footnote 64

^ Varon, 2008. p. 39: "... they were openly resentful of the fact that the three-fifths clause had translated into political supremacy for the South.

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 109: "[The federal ratio] hardly agreed with [the restrictionists] various interests for this apportionment to move across the Mississippi River. Tallmadge [remarked the trans-Mississippi region] 'had no claim to such unequal representation, unjust upon the other States."

^ Howe, 2004. p. 150: "The Missouri Compromise also concerned political power ... many [Northerners] were increasingly alarmed at the disproportionate political influence of the southern slaveholders ... [resenting the three-fifths clause]."

^ Wilentz, 2016. p. 102-103: "The three-fifths clause guaranteed the South a voting majority on some, but hardly all [critical matters] ... Indeed, the congressional bulwark of what became known, rightly, as the Slave Power proved not to be the House, but the Senate, where the three-fifths rule made no difference." And "The three-fifths clause certainly did not prevent the House from voting to exclude slavery from the new state of Missouri in 1819. The House twice passed [in the 15th Congress] by substantial margins, antislavery resolutions proposed by [Tallmadge] with the largely Northern Republican majority founding its case on Jefferson's Declaration [of Independence] ... The antislavery effort would die in the Senate, where, again, the three-fifths clause made no difference."

^ Howe, 2004. p. 150: "...but if slavery were on the road to ultimate extinction in Missouri, the state might not vote with the proslavery bloc. In such power calculations, the composition of the Senate was of even greater moment than that of the House ... So the South looked to preserve its sectional equality in the Senate."

^ Varon, 2008. p. 40: "[T]he North's demographic edge [in the House] did not translate into control over the federal government, for that edge was blunted by constitutional compromises. The fact that the Founders had decided that each state, however large or small, would elect two senators meant the South's power in the Senate was disproportionate to its population, and that maintaining a senatorial parity between North and South depended on bringing in equal numbers of free and slave states.

Ammons, 1971. p. 450: "The central concern in the debates ... had been over the [senatorial] balance of power, for the Southern congressmen had concentrated their objections upon the fact that the admission of Missouri would forever destroy the equal balance then existing between [the number of] free and slave states."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 379: "At stake were the terms of admission to the Union of the newest state, Missouri. The main issue seemed simple enough, but the ramifications were not. Since 1815, in a flurry of state admissions, the numbers of new slave and free states had been equal, leaving the balance of slave and free states nationwide and in the Senate equal. The balance was deceptive. In 1818, when Illinois gained admission to the Union, antislavery forces won a state constitution that formally barred slavery but included a fierce legal code that regulated free blacks and permitted the election of two Southern-born senators. In practical terms, were Missouri admitted as a slave state, the Southern bloc in the Senate might enjoy a four-vote, not a two-vote majority.

Howe, 2004. p. 150

^ Wilentz, 2016. p. 102: "The congressional bulwark of what came to be known, rightly, as the Slave Power proved not to be the House but the Senate ..."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 114-115: "The political and sectional problem originally raised by the Tallmadge amendment, the problem of the control of the Mississippi Valley, quite failed to conceal [the] profound renumciation of human rights."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 387: "According to the Republicans, preservation of individual rights and strict construction of the Constitution demanded the limitation of slavery and the recognition ... Earlier and more passionately than the Federalists, Republicans rooted their antislavery arguments, not in political expediency, but in egalitarian morality—the belief, as Fuller declared, that it was both "the right and duty of Congress" to restrict the spread "of the intolerable evil and the crying enormity of slavery." Individual rights, the Republicans asserted, has been defined by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence ... If all men were created equal, as Jefferson said, then slaves, as men, were born free and, under any truly republican government, entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As the Constitution, in Article 4, section 4, made a republican government in the states a fundamental guarantee of the Union, the extension of slavery into areas where slavery did not exist in 1787 was not only immoral but unconstitutional."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 110

Varon, 2008. p. 39: "The Missouri debates, first and foremost, arguments about just what the compromises of 1787 really meant – what the Founders really intended.

^ Varon, 2008. p. 40: "Tallmadge [and his supporters] made the case that it was constitutional for Congress to legislate the end of slavery in Missouri after its admission to statehood [to determine] the details of its government."

Wilentz, 2005. p. 123

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 387: "According to the Republicans, preservation of individual rights and strict construction of the Constitution demanded the limitation of slavery and the recognition, in Fuller's words, that "all men have equal rights", regardless of color. Earlier and more passionately than the Federalists, Republicans rooted their antislavery arguments, not in political expediency, but in egalitarian morality—the belief, as Fuller declared, that it was both "the right and duty of Congress" to restrict the spread "of the intolerable evil and the crying enormity of slavery." Individual rights, the Republicans asserted, has been defined by Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence—"an authority admitted in all parts of the Union [as] a definition of the basis of republican government." If all men were created equal, as Jefferson said, then slaves, as men, were born free and, under any truly republican government, entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As the Constitution, in Article 4, section 4, made a republican government in the states a fundamental guarantee of the Union, the extension of slavery into areas where slavery did not exist in 1787 was not only immoral but unconstitutional."

^ Ellis, 1995. p. 266: "[T]he idea of prohibiting the extension of slavery into the western territories could more readily be seen as a fulfillment rather than a repudiation of the American Revolution, indeed as the fulfillment of Jefferson's early vision of an expansive republic populated by independent farmers unburdened by the one legacy that defied the principles of 1776 [slavery]"

^ ab Varon, 2008. p. 40

^ Wilentz, 2004. p, 379: footnote (8)

Ellis, 1995. p.266

^ Ellis, 1995. p.266-267: "[W]hat most rankled Jefferson [and southern Republicans] about the debate over the Missouri Question was that it was happening at all. For the debate represented a violation of the sectional understanding and the vow of silence ..."

^ Ellis, 1995. p. 268: "Only a gradual policy of emancipation was feasible, but the mounting size of the slave population made any gradual policy unfeasible ... and made any southern-sponsored solution extremely unlikely ... the enlightened southern branch of the revolutionary generation ... had not kept its promise to [relinquish slavery]." and p. 270: "All [of the Revolutionary generation at the time] agreed that ending slavery depended on confining it to the South ... isolating it in the South."

^ Ammons, 1971. p. 450: "...if slavery were confined to the states where it existed, the whites would eventually desert these regions ... would the [abandoned area] be accepted as black republics with representation in Congress? ... a common southern view [held] that the best way to ameliorate the lot of the slave and [achieving] emancipation, was by distributing slavery throughout the Union."

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 110

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 379-380

^ Howe, 2004. p. 148

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 111

Holt, 2004. p. 5-6

Wilentz, 2004. p. 380

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 111

^ Howe, 2004. p. 150

^ Burns, 1982. P. 242-243

^ Dangerfield, 1965. p. 111

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 380

^ Wilentz, 2004 p. 380 (Table 1 adapted from Wilentz)

^ Ammons, 1971. p. 454: "[President Monroe] and other Republicans were convinced that behind the attempt to exclude slavery from Missouri was a carefully concealed plot to revive the party divisions of the past either openly as Federalism or some new disguise. He drew his conclusion from several circumstances ... [Rufus King had emerged] as the outstanding congressional spokesman of the restrictionists ... [and that he] was in league with De Witt Clinton [who was pursuing his own presidential ambitions outside the Republican Party] ... to [Monroe's] way of thinking, the real objective of these leaders was power ... that they were willing to accept disunion if their plans could not be achieved in any other fashion ... [and that] Tallmadge was one of Clinton's close associates [added weight to his suspicions] ... [ The union could not] survive the formation of parties based on a North-South sectional alignment."

Ellis, 1995. p. 270: "The more [Thomas Jefferson] though about the debate over Missouri, the more he convinced himself that the real agenda had little to do with slavery at all"

^ Howe, 2004. p. 151: "Republicans [in Congress] accused [King] of fanning flames of northern sectionalism is revitalize the Federalist Party."

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 119: "An insinuation, made very early in the House [by Mr. Holmes, who wish to detach the Maine statehood from that of Missouri] was the first to suggest that the purpose behind the movement to restrict [slavery in] Missouri was a new alignment of parties. New York, he hinted, was the center of this conspiracy; and he barely concealed his belief that Rufus King and [Governor] De Witt Clinton – a Federalist and (many believed) a crypto-Federalist – were its leaders." And "In 1819 [King had expressed himself] with ... too great a warmth in favor of the Tallmadge amendment, and in January 1820, he was re-elected to the by a legislative composed [of both New York factions] ... From then onward, the notion that a Federalist-Clintonian alliance was 'plotting' to build a new northern party out of the ruins of the Republican Ascendency was never absent from the Missouri debates."

^ Ellis, 1995. p. 270-271

^ Brown, 1966. p. 23

^ Ellis, 1995. p. 217: "'Consolidation' was the new term that Jefferson embraced – other Virginians were using it too – to label the covert goals of these alleged conspirators. In one sense the consolidations were simply the old monarchists in slightly different guise ... [a] flawed explanation of ... the political forces that had mobilized around the Missouri Question [suspected of being organized] to maximize its coercive influence over popular opinion."

^ Wilentz, 2004. p. 3885-386: "No evidence exists to show that Clinton or any New England Federalist helped to instigate the Tallmadge amendments. Although most Northern Federalists backed restriction, they were hardly monolithic on the issue; indeed, in the first key vote on Tallmadge's amendments over Missouri, the proportion of Northern Republicans who backed restriction surpassed that of Northern Federalists. "It is well known", the New Hampshire Republican William Plumer, Jr. observed of the restrictionist effort, "that it originated with Republicans, that it is supported by Republicans throughout the free states; and that the Federalists of the South are its warm opponents."

Dangerfield, 1965. p. 122: "There is no trace of a Federalist 'plot', at least as regards the origins of the Tallmadge amendment; there was never a Federalist-Clinton 'conspiracy' ..."

Howe, 2004. p. 151

^ Ammons, 1971. p. 454-455: "Although there is nothing to suggest that the political aspirations of the Federalists were responsible for the move to restrict slavery in Missouri, once the controversy erupted for Federalists were not unwilling to consider the possibility of a new political alignment. They did not think in terms of a revival of Federalism, but rather of establishing a liaison with discontented Republicans which would offer them an opportunity to re-engage in political activity in some other form than a permanent minority." And p. 458: "In placing this emphasis upon political implications of the conflict over Missouri [e.g. Federalist 'plots' and 'consolidation'], Monroe and other Southerners obscured the very real weight of antislavery sentiment involved in the restrictionist movement."

^ Dixon, 1899 p. 184

^ White, Deborah Gray (2013). Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 215..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Dixon, 1899 pp. 49–51

^ Forbes, 1899 pp. 36–38

^ Dixon, 1899 pp. 58–59

^ abc Greeley, Horace. A History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension Or Restriction in the United States, p. 28 (Dix, Edwards & Co. 1856, reprinted by Applewood Books 2001).

^ Dixon, 1899 pp. 116–117

^ Paul Finkelman (2011). Millard Fillmore: The 13th President, 1850–1853. Henry Holt. p. 39.

^ Leslie Alexander (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 340.

^ Brown, 1964 p.69

^ Peterson, 1960 p.189

^ "Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes". April 22, 1820. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ "Maine Becomes a State". Library of Congress. March 15, 1820. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ "Missouri Becomes a State". Library of Congress. August 10, 1821. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ "Arkansas Becomes a State". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

^ White, Deborah Gray (2013). Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 215–216.

^ "Lincoln at Peoria". Retrieved November 18, 2012.

^ "Peoria Speech, October 16, 1854". National Park Service. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Brown, Richard H. (1970) [Winter 1966], "Missouri Crisis, Slavery, and the Politics of Jacksonianism", in Gatell, Frank Otto, Essays on Jacksonian America, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 5–72

Burns, James MacGregor (1982), The Vineyard of Liberty, Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0394505468

Dangerfield, George (1965), The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815–1828, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 9780881338232

Ellis, Joseph A. (1996), American sphinx: the character of Thomas Jefferson, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 978-0679764410

Howe, Daniel W. (2007), What hath God wrought: the transformation of America, 1815–1848, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195392432

Malone, Dumas; Rauch, Basil (1960), Empire for Liberty: The Genesis and Growth of the United States of America, New York: Appleton-Century Crofts

Miller, William L. (1995), Arguing about Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress, Borzoi Books, Alfred J. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-56922-9

Staloff, Darren (2005), Hamilton, Adams, Jefferson: The Politics of Enlightenment and the American Founding, New York: Hill and Wang, ISBN 0-8090-7784-1

Varon, Elizabeth R. (2008), Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-8078-3232-5

Wilentz, Sean (Fall 2004), "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited", The Journal of the Historical Society, IV (3)

Wilentz, Sean (2016), The Politicians & the Egalitarians: The Hidden History of American Politics, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-28502-4

Further reading

Brown, Richard Holbrook (1964), The Missouri compromise: political statesmanship or unwise evasion?, Heath, p. 85

Dixon, Mrs. Archibald (1899). The true history of the Missouri compromise and its repeal. The Robert Clarke Company. p. 623.

Forbes, Robert Pierce (2007). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America. University of North Carolina Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780807831052.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Howe, Daniel Walker (Summer 2010), "Missouri, Slave Or Free?", American Heritage, 60 (2): 21–23

Humphrey, D. D., Rev. Heman (1854). THE MISSOURI COMPROMISE. Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Reed, Hull & Peirson. p. 32.

Moore, Glover (1967), The Missouri controversy, 1819–1821, University of Kentucky Press (Original from Indiana University), p. 383

Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind. University of Virginia Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8139-1851-0.

Wilentz, Sean (2004), "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited", Journal of the Historical Society, 4 (3): 375–401

White, Deborah Gray (2013), Freedom On My Mind: A History of African Americans, Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 215–216

Woodburn, James Albert (1894), The historical significance of the Missouri compromise, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, p. 297

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Missouri Compromise |

- Library of Congress – Missouri Compromise and Related Resources

- EDSITEment's lesson plan Early Threat of Session Missouri Compromise 1820

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory