Mughal gardens

The Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan, is among the most famous of all Mughal-era gardens

| Mughal gardens | |

|---|---|

| Type | Public parks |

| Created | 1526 (1526) |

| Status | Open year round |

Mughal gardens are a group of gardens built by the Mughals in the Persian style of architecture. This style was heavily influenced by the Persian gardens particularly the Charbagh structure.[1] Significant use of rectilinear layouts are made within the walled enclosures. Some of the typical features include pools, fountains and canals inside the gardens.

Contents

1 History

2 Design and symbolism

3 Sites

3.1 Afghanistan

3.2 India

3.3 Pakistan

3.4 Bangladesh

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

7 External links

History

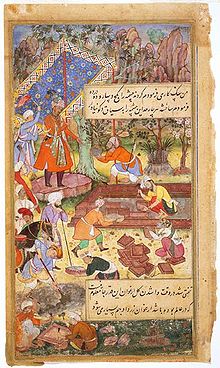

Mughal Emperor Babur supervising the creation of a garden

The founder of the Mughal empire, Babur, described his favourite type of garden as a charbagh. They use the term bāgh, baug, bageecha or bagicha for garden. This word developed a new meaning in India, as Babur explains; India lacked the fast-flowing streams required for the Central Asian charbagh. The Aram Bagh of Agra is thought to have been the first charbagh in South Asia. India, Bangladesh and Pakistan have a number of Mughal gardens which differ from their Central Asian predecessors with respect to "the highly disciplined geometry". An early textual references about Mughal gardens are found in the memoirs and biographies of the Mughal emperors, including those of Babur, Humayun and Akbar. Later references are found from "the accounts of India" written by various European travellers (Bernier for example). The first serious historical study of Mughal gardens was written by Constance Villiers-Stuart, with the title Gardens of the Great Mughals (1913).[2] Her husband was a Colonel in Britain's Indian army. This gave her a good network of contacts and an opportunity to travel. During their residence at Pinjore Gardens, Mrs. Villiers-Stuart also had an opportunity to direct the maintenance of an important Mughal garden. Her book makes reference to the forthcoming design of a garden in the Government House at New Delhi (now known as Rashtrapati Bhavan).[2] She was consulted by Edwin Lutyens, and this may have influenced his choice of Mughal style for this project. Recent scholarly work on the history of Mughal gardens has been carried out under the auspicious guidance of Dumbarton Oaks (including Mughal Gardens: Sources, Places, Representations, and Prospects edited by James L. Wescoat, Jr. and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn) and the Smithsonian Institution. Some examples of Mughal gardens are Shalimar Gardens (Lahore), Lalbagh Fort at Dhaka, and Shalimar Bagh (Srinagar).

Mughal gardens at the Taj Mahal

From the beginnings of the Mughal Empire, the construction of gardens was a beloved imperial pastime.[3] Babur, the first Mughal conqueror-king, had gardens built in Lahore and Dholpur. Humayun, his son, does not seem to have had much time for building—he was busy reclaiming and increasing the realm—but he is known to have spent a great deal of time at his father’s gardens.[4] Akbar built several gardens first in Delhi,[5] then in Agra, Akbar’s new capital.[6] These tended to be riverfront gardens rather than the fortress gardens that his predecessors built. Building riverfront rather than fortress gardens influenced later Mughal garden architecture considerably.

Akbar’s son, Jahangir, did not build as much, but he helped to lay out the famous Shalimar garden and was known for his great love for flowers.[7] Indeed, his trips to Kashmir are believed to have begun a fashion for naturalistic and abundant floral design.[8]

Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan, marks the apex of Mughal garden architecture and floral design. He is famous for the construction of the Taj Mahal, a sprawling funereal paradise in memory of his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal.[9] He is also responsible for the Red Fort at Delhi which contains the Mahtab Bagh, a night garden that was filled with night-blooming jasmine and other pale flowers.[10] The pavilions within are faced with white marble to glow in the moonlight. This and the marble of the Taj Mahal are inlaid with semiprecious stone depicting scrolling naturalistic floral motifs, the most important being the tulip, which Shah Jahan adopted as a personal symbol.[11]

Design and symbolism

Shalimar Bagh, Srinagar, Kashmir

Mughal gardens design derives primarily from the medieval Islamic garden, although there are nomadic influences that come from the Mughals’ Turkish-Mongolian ancestry. Julie Scott Meisami describes the medieval Islamic garden as “a hortus conclusus, walled off and protected from the outside world; within, its design was rigidly formal, and its inner space was filled with those elements that man finds most pleasing in nature. Its essential features included running water (perhaps the most important element) and a pool to reflect the beauties of sky and garden; trees of various sorts, some to provide shade merely, and others to produce fruits; flowers, colorful and sweet-smelling; grass, usually growing wild under the trees; birds to fill the garden with song; the whole is cooled by a pleasant breeze. The garden might include a raised hillock at the center, reminiscent of the mountain at the center of the universe in cosmological descriptions, and often surmounted by a pavilion or palace.”[12] The Turkish-Mongolian elements of the Mughal garden are primarily related to the inclusion of tents, carpets and canopies reflecting nomadic roots. Tents indicated status in these societies, so wealth and power were displayed through the richness of the fabrics as well as by size and number.[13]

Fountainry and running water was a key feature of Mughal garden design. Water-lifting devices like geared Persian wheels (saqiya) were used for irrigation and to feed the water-courses at Humayun's Tomb in Delhi, Akbar's Gardens in Sikandra and Fatehpur Sikhri, the Lotus Garden of Babur at Dholpur and the Shalimar Bagh in Lahore. Royal canals were built from rivers to channel water to Delhi, Fatehpur Sikhri and Lahore. The fountains and water-chutes of Mughal gardens represented the resurrection and regrowth of life, as well as to represent the cool, mountainous streams of Central Asia and Afghanistan that Babur was famously fond of. Adequate pressure on the fountains was applied through hydraulic pressure created by the movement of Persian wheels or water-chutes (chaadar) through terra-cotta pipes, or natural gravitational flow on terraces. It was recorded that the Shalimar Bagh in Lahore had 450 fountains, and the pressure was so high that water could be thrown 12 feet into the air, falling back down to create a rippling floral effect on the surface of the water.[14]

The Mughals were obsessed with symbol and incorporated it into their gardens in many ways. The standard Quranic references to paradise were in the architecture, layout, and in the choice of plant life; but more secular references, including numerological and zodiacal significances connected to family history or other cultural significance, were often juxtaposed. The numbers eight and nine were considered auspicious by the Mughals and can be found in the number of terraces or in garden architecture such as octagonal pools.[15]

Sites

Pinjore Gardens in Haryana

Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi, India

Afghanistan

Bagh-e Babur (Kabul)

India

Humayun's Tomb, Nizamuddin East, Delhi

Taj Mahal, Agra

Mehtab Bagh, Agra

- Safdarjung's Tomb

Shalimar Bagh (Srinagar), Jammu and Kashmir

Nishat Gardens, Jammu and Kashmir

Yadavindra Gardens, Pinjore

Khusro Bagh, Allahabad

- Roshanara Bagh

Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi (1911-1931)- Vernag

- Chashma Shahi

- Pari Mahal

- Achabal Gardens

- Qudsia Bagh

- Pune-Okayama Friendship Garden-Phase_II

Pakistan

- Chauburji

- Lahore Fort

- Shahdara Bagh

- Shalimar Gardens (Lahore)

Tomb of Jahangir, Lahore

- Hazuri Bagh

Hiran Minar (Sheikhupura)- Mughal Garden Wah

Bangladesh

- Lalbagh Fort

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mughal gardens. |

- Charbagh gardens

- Lal Bagh

- Indo-Persian culture

References

^ Penelope Hobhouse; Erica Hunningher; Jerry Harpur (2004). Gardens of Persia. Kales Press. pp. 7–13. ISBN 9780967007663..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Villiers-Stuart, Constance Mary (1913). Gardens of the great Mughals. A. & C. Black.

^ Jellicoe, Susan. "The Development of the Mughal Garden", MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p109

^ Hussain, Mahmood; Rehman, Abdul; Wescoat, James L. Jr. The Mughal Garden: Interpretation, Conservation and Implications, Ferozsons Ltd., Lahore (1996). p 207

^ Neeru Misra and Tanay Misra, Garden Tomb of Humayun: An Abode in Paradise, Aryan Books International, Delhi, 2003

^ Koch, Ebba. “The Char Bagh Conquers the Citadel: an Outline of the Development if the Mughal Palace Garden,” Hussain, Mahmood; Rehman, Abdul; Wescoat, James L. Jr. The Mughal Garden: Interpretation, Conservation and Implications, Ferozsons Ltd., Lahore (1996). p. 55

^ With his son Shah Jahan. Jellicoe, Susan “The Development of the Mughal Garden” MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p 115

^ Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982)p 121-123.

^ Villiers-Stuart, C. M. (1913). The Gardens of the Great Mughals. Adam and Charles Black, London. p. 53.

^ Jellicoe, Susan “The Development of the Mughal Garden” MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p 121

^ Tulips are metaphorically considered to be "branded by love" in Persian poetry. Meisami, Julie Scott. "Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (May, 1985), p. 242

^ Meisami, Julie Scott. “Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (May, 1985), p. 231; The Old Persian word pairideaza (transliterated to English as paradise) means “walled garden”. Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982), p. 1.

^ Allsen, Thomas T. Commodity and Exchange n the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles, Cambridge University Press (1997). p 12-26

^ Fatima, Sadaf (2012). "Waterworks in Mughal Gardens". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 1268–1278. JSTOR 44156328.

^ Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982). p100

Further reading

Crowe, Sylvia (2006). The gardens of Mughul India: a history and a guide. Jay Kay Book Shop. ISBN 978-8-187-22109-8.

- Lehrman, Jonas Benzion (1980). Earthly paradise: garden and courtyard in Islam. University of California Press.

ISBN 0-520-04363-4.

Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press.

ISBN 0-8122-4025-1.

Wescoat, James L.; Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (1996). Mughal gardens: sources, places, representations, and prospects. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-884-02235-0.

External links

- Gardens of the Mughal Empire, Smithsonian Institution

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum