Szombathely

Szombathely | ||

|---|---|---|

City with county rights | ||

| Szombathely Megyei Jogú Város | ||

| ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Queen of the West | ||

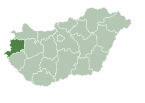

Szombathely Location of Szombathely | ||

| Coordinates: 47°14′06″N 16°37′19″E / 47.23512°N 16.62191°E / 47.23512; 16.62191Coordinates: 47°14′06″N 16°37′19″E / 47.23512°N 16.62191°E / 47.23512; 16.62191 | ||

| Country | ||

| Region | Western Transdanubia | |

| County | Vas | |

| District | Szombathely | |

| Established | 43 century AD (Savaria) | |

| City status | 1407 | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Tivadar Puskás (Fidesz-KDNP) | |

| • Deputy Mayor | Tibor Koczka (Fidesz-KDNP) Károly Illés (Fidesz-KDNP) Miklós Molnár (Pro Savaria) | |

| • Town Notary | Dr Ákos Károlyi | |

| Area | ||

| • City with county rights | 97.52 km2 (37.65 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 209 m (686 ft) | |

| Population (2017) | ||

| • City with county rights | 78,025[1] | |

| • Rank | 10th | |

| • Density | 800.09/km2 (2,072.2/sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 147,920 (10th)[2] | |

| Demonym(s) | szombathelyi | |

Population by ethnicity [3] | ||

| • Hungarians | 83.0% | |

| • Germans | 2.0% | |

| • Gypsies | 0.8% | |

| • Croats | 0.6% | |

| • Slovenes | 0.2% | |

| • Slovaks | 0.1% | |

| • Romanians | 0.1% | |

| • Bulgarians | 0.1% | |

| • Others | 0.7% | |

Population by religion [4] | ||

| • Roman Catholic | 52.2% | |

| • Greek Catholic | 0.2% | |

| • Lutherans | 2.7% | |

| • Calvinists | 2.0% | |

| • Other | 1.1% | |

| • Non-religious | 9.8% | |

| • Unknown | 32.0% | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Postal code | 9700 | |

| Area code | (+36) 94 | |

| Patron Saint | Martin of Tours | |

| Motorways | M86, M87 (planned), M9 (planned) | |

| Distance from Budapest | 221 km (137 mi) West | |

| Airport | Szombathely | |

| NUTS 3 code | HU222 | |

| MP | Csaba Hende (Fidesz) | |

| Website | www.szombathely.hu | |

Szombathely (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈsombɒthɛj]; see also other alternative names) is the 10th largest city in Hungary. It is the administrative centre of Vas county in the west of the country, located near the border with Austria. Szombathely lies by the streams Perint and Gyöngyös (literally "pearly"), where the Alpokalja (Lower Alps) mountains meet the Little Hungarian Plain. The oldest city in Hungary, it is known as the birthplace of Saint Martin of Tours.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Savaria, the Roman city

2.2 Savaria/Szombathely in the Middle Ages

2.3 Szombathely in the 16th to 19th century

2.4 Szombathely in the 20th and 21st centuries

2.5 History of Szombathely's Jewish communities

2.6 Population

3 Representation in other media

4 Climate

5 Media

5.1 Mediumwave broadcasting station

6 International relations

6.1 Twin towns and sister cities

7 Notable people associated with Szombathely

8 Gallery

9 References

10 External links

Etymology

The name Szombathely is from Hungarian szombat, "Saturday" and hely, "place", referring to its status as a market town, and the medieval markets held on Saturday every week.

The Latin name Savaria or Sabaria comes from Sibaris, the Latin name of the river Gyöngyös (German Güns). The root of the word is the Proto-Indo-European word *seu, meaning "wet". The Austrian overflowing of the Gyöngyös/Güns is called Zöbern, most probably a derivation of its Latin name. The city is known in Croatian as Sambotel, in Slovene as Sombotel and in Yiddish as Sambathali.

The German name, Steinamanger, means "stone on the green" (Stein am Anger). The name was coined by German settlers who encountered the ruins of the Roman city of Savaria.[citation needed]

History

Savaria, the Roman city

Temple of Isis, reconstruction

Szombathely is the oldest recorded city in Hungary. It was founded by the Romans[5] in 45 AD under the name of Colonia Claudia Savariensum (Claudius' Colony of Savarians), and it was the capital of the Pannonia Superior province of the Roman Empire. It lay close to the important "Amber Road" trade route. The city had an imperial residence, a public bath and an amphitheatre. In 2008, remains of a mithraeum were discovered.

Emperor Constantine the Great visited Savaria several times. He ended the persecution of Christians, which previously claimed the lives of many people in the area, including Bishop St. Quirinus and St. Rutilus. The emperor reorganised the colonies and made Savaria the capital of the province Pannonia Prima. This era was the height of prosperity for Savaria: its population grew, and new buildings were erected, among them theatres and churches. St. Martin of Tours was born here.[6] After the death of Emperor Valentinian III, the Huns invaded Pannonia. Attila's armies occupied Savaria between 441 and 445. The city was destroyed by an earthquake in 456.

Óperint Street - Memorial plaque to Bishop St. Quirinus, remembering the anniversary of his death in 1700

Savaria/Szombathely in the Middle Ages

Interior of the Cathedral

The city remained inhabited throughout the Middle Ages. Its city walls were restored, and new buildings were constructed using the stones from the remains of Roman buildings. Much of the Latin population moved away, mostly to Italy, while new settlers, mostly Goths and Longobards, arrived.

In the 6th–8th centuries, the city was inhabited by Pannonian Avars and Slavic tribes. In 795, the Franks defeated these peoples and occupied the city. Charlemagne visited the city where St. Martin was born.

King Arnulf of the Franks gave the city to the archbishop of Salzburg in 875. It is likely that the castle was built around this time, using the stones from the Roman baths. Around 900, they were succeeded by Hungarians, who became the dominant population.

In 1009, Stephen I gave the city to the newly founded Diocese of Győr. The city suffered during the war between King Sámuel Aba and Holy Roman Emperor Henry III, between 1042 and 1044.

Szombathely was destroyed during the Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1241–1242 but was rebuilt shortly after. It was granted Free royal town status in 1407. In 1578, it became the capital of Vas comitatus.[7] The city prospered. In 1605 it was occupied by the armies of István Bocskai.

Szombathely in the 16th to 19th century

Szombathely Franciscan Church

During the Ottoman occupation of Hungary, the Ottomans invaded the area twice, first in 1664, when they were defeated at the nearby town of Szentgotthárd. Nearly twenty years later, they invaded again in 1683, during the Battle of Vienna. The city walls protected Szombathely both times.

A peaceful period followed the retreat of the Turks until Prince Rákóczi's rebellion against the Habsburgs in the early 18th century. During the rebellion, the city residents supported the prince. The city was occupied by Habsburg armies in 1704, freed in November 1705, then occupied alternately by the two armies over the next years. In June 1710, more than 2,000 people lost their lives in a plague, and on May 3, 1716, the city was destroyed by a fire.

After such losses throughout the region, the Habsburg Crown recruited Germans to resettle the depopulated areas, particularly along the Danube River. They were valued for their farming abilities. The Crown allowed them to keep their language and religion. As a result, the city had a German majority for a long time. With increased population, the city began to prosper again. With the support of Ferenc Zichy, Bishop of Győr, a high school was built in 1772. The Diocese of Szombathely was founded in 1777 by Maria Theresa. The new bishop of Szombathely, János Szily, did much for the city: he had the ruins of the castle demolished and had new buildings constructed, including a cathedral, the episcopal palace complex, and a school (opened in 1793).

In 1809, Napoleon's armies occupied the city and held it for 110 days, following a short battle on the main square. In 1817, two-thirds of the city was destroyed by fire. In 1813, a cholera epidemic claimed many lives.

During the revolution in 1848-49, Szombathely supported the revolution. There were no battles in the immediate area because the city remained under Habsburg rule. The years after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 brought prosperity. A railway line reached the city in 1865, and in the 1870s Szombathely became a major railway junction. In 1885 the city annexed the nearby villages Ó-Perint and Szentmárton and increased its area.

In the 1890s, when Gyula Éhen was the mayor, the city underwent significant infrastructure development: roads were paved, a sewage system built, and the tram line was built to connect the rail station, the downtown, and the Calvary Church. Private and public interests built the City Casino, the Grand Hotel (Kovács Szálló, later Hotel Savaria), and the area's first orphanage. In forty years, the population became four times larger.

During the mayoralty of Tóbiás Brenner, this prosperity continued. A museum, public bath, monasteries, and several new downtown mansions were built. A school of music and orchestra were founded.

Szombathely in the 20th and 21st centuries

The County Hall

Main square

New M86 motorway in Szombathely

After the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost many of its western territories to Austria. Only 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the new state border, Szombathely ceased to be the centre of Western Hungary. Trying to regain the throne of Hungary, Charles IV visited the city, where he was greeted with enthusiasm, but he failed to regain power.

Between the world wars, Szombathely prospered. Many schools were founded, and between 1926 and 1929, the most modern hospital of the Transdanubian region was built.

During World War II, as with many other towns in the region, Szombathely was strategic due to the railway, junction, marshalling yards, local aerodrome, and barracks. The town formed part of the logistical military infrastructure supporting Axis forces. In 1944 and 1945, the town and locality were bombed by day on several occasions by aircraft of the US 15th Air Force; at night, bombing runs were made by aircraft from the Royal Air Force 205 Group. These aircraft operated from bases in Italy.

On 28 March 1945, the 6th SS Panzer and 6th Armies were pushed back by an assault from the east across the Raba River by the 46th and 26th Armies of the USSR and the 3rd Ukrainian Front. Soviet forces took control of Szombathely on 29 March 1945.

After the war the city grew, absorbing many nearby villages (Gyöngyöshermán, Gyöngyösszőlős, Herény, Kámon, Olad, Szentkirály, Zanat and Zarkaháza). The government of Hungary was dominated by the Soviet Union. During the revolution in 1956, the city was occupied by the Soviet army.

In the 1970s, the city was industrialized, and many factories were built. In the 1980s, the city prospered, and several new public buildings were built. These included the County Library, public indoor swimming pools, and a gallery.

In 2006, the refurbishing of the city centre's main square was completed, with financial assistance from European Union funds.

28 June 2014 from the highway is also available in the city, having opened the M86 motorway.[8]

History of Szombathely's Jewish communities

In 1567, Emperor Maximilian II granted the town the privilege of allowing none but Catholics to dwell within its walls. By the 17th and 18th centuries, although the municipal authorities rented shops to Jews, the latter were permitted to remain in the town only during the day, and then only without their families. They lived outside in their own community, known as a shtetl. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, only three or four Jewish families lived in the city.[citation needed]

The residents of the shtetl Stein-am-Anger, dwelt in the outlying districts (now united into one municipality). They separated in 1830 from the community of Rechnitz (Rohonc), of which they had previously formed a part, and were henceforth known as the community of Szombathely. When the Jews of Hungary were emancipated by the law of 1840, the city allowed them to live there. In the unrest of the revolution of 1848, many Jews were attacked and their places looted[citation needed]; they were threatened with expulsion. The authorities intervened and restored peace. The community quickly developed in the city.

The first Jewish elementary school was founded in 1846, and was organized as a normal school in 1905, with four grades and about 230 pupils. The first synagogue was built by the former lord of the town, Duke Batthyányi, who sold it to the Jews. In 1880 the community supported building a large temple, one of the most beautiful in Hungary. Designed by Ludwig Schöne, it combined Oriental and Romantic elements.[citation needed]

The founder of the community and its first rabbi was Ludwig Königsberger (d. 1861); he was succeeded in turn by Leopold Rockenstein, Joseph Stier([1]), and Béla Bernstein (called in 1892; [2]). A small Orthodox congregation, numbering about 60 or 70 members, separated from the main body in 1870. From 1896 to 1898 Pál Jungreis was rabbi of the Orthodox community but his convictions were not tolerated so Márk Benedikt was appointed rabbi. [3]

According to the 1910 census, 10.1% of the city's population, or 3125 people, were Jewish by religion. By then they were merchants and professionals, an integral part of the city's culture.

In World War II, during the occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany, 4228 Jews were deported (July 4–6, 1944) from Szombathely to Auschwitz. The community was essentially destroyed. Since 1975, the former Jewish temple has been adapted for use as a concert hall. A memorial outside commemorates the Jews deported in World War II.

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1784 | 2,472 | — |

| 1850 | 8,338 | +237.3% |

| 1870 | 12,934 | +55.1% |

| 1880 | 17,055 | +31.9% |

| 1890 | 20,405 | +19.6% |

| 1900 | 29,959 | +46.8% |

| 1910 | 37,289 | +24.5% |

| 1920 | 42,275 | +13.4% |

| 1930 | 46,379 | +9.7% |

| 1941 | 50,935 | +9.8% |

| 1949 | 47,589 | −6.6% |

| 1960 | 54,758 | +15.1% |

| 1970 | 65,297 | +19.2% |

| 1980 | 82,851 | +26.9% |

| 1990 | 85,617 | +3.3% |

| 2001 | 81,920 | −4.3% |

| 2011 | 78,884 | −3.7% |

| 2018 | 77,984 | −1.1% |

| 2021! | 79,000 | +1.3% |

| 2031! | 81,000 | +2.5% |

| 2041! | 83,000 | +2.5% |

Representation in other media

James Joyce wrote that the character Virág Rudolf, the father of Leopold Bloom, his Jewish Irish protagonist in Ulysses, was from Szombathely.- Savaria appears in Total War: Attila as a Roman settlement in Pannonia

Climate

| Climate data for Szombathely, Hungary (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) | 4.5 (40.1) | 9.9 (49.8) | 15.4 (59.7) | 20.2 (68.4) | 23.2 (73.8) | 25.5 (77.9) | 24.9 (76.8) | 21.1 (70.0) | 15.4 (59.7) | 8.0 (46.4) | 3.1 (37.6) | 14.4 (57.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) | −2.8 (27.0) | 0.0 (32.0) | 4.2 (39.6) | 8.5 (47.3) | 11.9 (53.4) | 13.3 (55.9) | 13.0 (55.4) | 9.8 (49.6) | 4.9 (40.8) | 0.8 (33.4) | −2.9 (26.8) | 4.7 (40.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29 (1.1) | 26 (1.0) | 34 (1.3) | 40 (1.6) | 72 (2.8) | 77 (3.0) | 78 (3.1) | 72 (2.8) | 52 (2.0) | 48 (1.9) | 52 (2.0) | 31 (1.2) | 611 (23.8) |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[9] | |||||||||||||

Media

Mediumwave broadcasting station

Near Szombathely, there is since 1955 at 47°12′02″N 16°39′43″E / 47.20056°N 16.66194°E / 47.20056; 16.66194 (Szombathely Mediumwave Transmitter) a mediumwave broadcasting station operated on 1251 kHz with 25 kW, which uses as antenna two 60 metres tall free-standing radio towers insulated against ground. It is the only mediumwave broadcasting station in Hungary using free-standing self radiating towers.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Szombathely is twinned with:

|

|

Notable people associated with Szombathely

|

|

Gallery

County Hall of Vas County in the

Berzsenyi Dániel Square

Episcopal Palace in the

Berzsenyi Dániel Square

Holy Trinity column

in the Main Square

Dominican church in

the St Martin's Street

Dwelling house, Main Square 25.

House, Main Square 7.

House, Main Square 8.

House, Main Square 9.

Former savings bank building

Baroque style school building

in Szily János Street

Dwelling house in

the Szily János Street

House, Kossuth Lajos Street 21.

House, Kossuth Lajos Street 7.

House, Aréna Street 8.

Evangelic church in

the Körmendi Street

Owl Castle

References

^ KSH - Szombathely, 2011

^ Eurostat, 2016

^ KSH - Szombathely, 2011

^ KSH - Szombathely, 2011

^ Pliny the Elder, III, 146

^ Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum, I, 36

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2008-10-29.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link) .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ opened M86 Motorways Szombathely-Vát Archived 2014-06-28 at Archive.today

^

"Climatological Information for Szombathely, Hungary", Hong Kong Observatory, 2003, web:

HKO-Szombathely, Hungary.

^ "Twin cities". Retrieved 29 April 2014.

^ "Ramat Gan Sister Cities". Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. by Isidore Singer & Bela Bernstein

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. by Isidore Singer & Bela Bernstein

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Szombathely. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Steinamanger. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Szombathely. |

Official site of Szombathely[permanent dead link] - More historical and touristic information (in English)

Official site of the Savaria Historical Festival (in Hungarian)

Szombathely at funiq.hu (in English)