Phylum

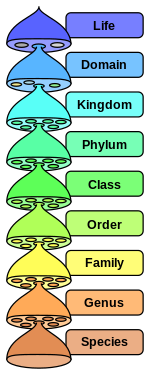

The hierarchy of biological classification's eight major taxonomic ranks. A kingdom contains one or more phyla. Intermediate minor rankings are not shown.

In biology, a phylum (/ˈfaɪləm/; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below Kingdom and above Class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants accepts the terms as equivalent.[1][2][3] Depending on definitions, the animal kingdom Animalia or Metazoa contains approximately 35 phyla, the plant kingdom Plantae contains about 14, and the fungus kingdom Fungi contains about 8 phyla. Current research in phylogenetics is uncovering the relationships between phyla, which are contained in larger clades, like Ecdysozoa and Embryophyta.[citation needed]

Contents

1 General description

1.1 Definition based on genetic relation

1.2 Definition based on body plan

2 Known phyla

2.1 Animals

2.2 Plants

2.3 Fungi

2.4 Protista

2.5 Bacteria

2.6 Archaea

3 See also

4 Notes

5 References

6 External links

General description

The term phylum was coined in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel from the Greek phylon (φῦλον, "race, stock"), related to phyle (φυλή, "tribe, clan").[4] In plant taxonomy, August W. Eichler (1883) classified plants into five groups named divisions, a term that remains in use today for groups of plants, algae and fungi.[1][5]

The definitions of zoological phyla have changed from their origins in the six Linnaean classes and the four embranchements of Georges Cuvier.[6]

Informally, phyla can be thought of as groupings of organisms based on general specialization of body plan.[7] At its most basic, a phylum can be defined in two ways: as a group of organisms with a certain degree of morphological or developmental similarity (the phenetic definition), or a group of organisms with a certain degree of evolutionary relatedness (the phylogenetic definition).[8] Attempting to define a level of the Linnean hierarchy without referring to (evolutionary) relatedness is unsatisfactory, but a phenetic definition is useful when addressing questions of a morphological nature—such as how successful different body plans were.[citation needed]

Definition based on genetic relation

The most important objective measure in the above definitions is the "certain degree" that defines how different organisms need to be to be members of different phyla. The minimal requirement is that all organisms in a phylum should be clearly more closely related to one another than to any other group.[8] Even this is problematic because the requirement depends on knowledge of organisms' relationships: as more data become available, particularly from molecular studies, we are better able to determine the relationships between groups. So phyla can be merged or split if it becomes apparent that they are related to one another or not. For example, the bearded worms were described as a new phylum (the Pogonophora) in the middle of the 20th century, but molecular work almost half a century later found them to be a group of annelids, so the phyla were merged (the bearded worms are now an annelid family).[9] On the other hand, the highly parasitic phylum Mesozoa was divided into two phyla (Orthonectida and Rhombozoa) when it was discovered the Orthonectida are probably deuterostomes and the Rhombozoa protostomes.[10]

This changeability of phyla has led some biologists to call for the concept of a phylum to be abandoned in favour of cladistics, a method in which groups are placed on a "family tree" without any formal ranking of group size.[8]

Definition based on body plan

A definition of a phylum based on body plan has been proposed by paleontologists Graham Budd and Sören Jensen (as Haeckel had done a century earlier). The definition was posited because extinct organisms are hardest to classify: they can be offshoots that diverged from a phylum's line before the characters that define the modern phylum were all acquired. By Budd and Jensen's definition, a phylum is defined by a set of characters shared by all its living representatives.

This approach brings some small problems—for instance, ancestral characters common to most members of a phylum may have been lost by some members. Also, this definition is based on an arbitrary point of time: the present. However, as it is character based, it is easy to apply to the fossil record. A greater problem is that it relies on a subjective decision about which groups of organisms should be considered as phyla.

The approach is useful because it makes it easy to classify extinct organisms as "stem groups" to the phyla with which they bear the most resemblance, based only on the taxonomically important similarities.[8] However, proving that a fossil belongs to the crown group of a phylum is difficult, as it must display a character unique to a sub-set of the crown group.[8] Furthermore, organisms in the stem group of a phylum can possess the "body plan" of the phylum without all the characteristics necessary to fall within it. This weakens the idea that each of the phyla represents a distinct body plan.[11]

A classification using this definition may be strongly affected by the chance survival of rare groups, which can make a phylum much more diverse than it would be otherwise.[12]

Known phyla

Animals

Total numbers are estimates; figures from different authors vary wildly, not least because some are based on described species,[13] some on extrapolations to numbers of undescribed species. For instance, around 25,000–27,000 species of nematodes have been described, while published estimates of the total number of nematode species include 10,000–20,000; 500,000; 10 million; and 100 million.[14]

Protostome | Bilateria | |

Deuterostome | ||

| Basal/disputed | ||

| Others | ||

| Phylum | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristic | Species described |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Acanthocephala | Thorny head | Thorny-headed worms[15]:278 | Reversible spiny proboscis that bears many rows of hooked spines | 7003110000000000000♠approx. 1,100 |

Acoelomorpha | Without gut | Acoels | No mouth or alimentary canal | N/K |

Annelida | Little ring :306 | Segmented worms | Multiple circular segment | 17,000 + extant |

Arthropoda | Jointed foot | Segmented bodies and jointed limbs, with Chitin exoskeleton | 7006125000000000000♠1,250,000+ extant;[13] 20,000+ extinct | |

Brachiopoda | Arm foot[15]:336 | Lampshells[15]:336 | Lophophore and pedicle | 7002300000000000000♠300-500 extant; 12,000+ extinct |

Bryozoa | Moss animals | Moss animals, sea mats, ectoprocts[15]:332 | Lophophore, no pedicle, ciliated tentacles, anus outside ring of cilia | 7003600000000000000♠6,000 extant[13] |

Chaetognatha | Longhair jaw | Arrow worms[15]:342 | Chitinous spines either side of head, fins | 7002100000000000000♠approx. 100 extant |

Chordata | With a cord | Chordates | Hollow dorsal nerve cord, notochord, pharyngeal slits, endostyle, post-anal tail | 7004550000000000000♠approx. 55,000+[13] |

Cnidaria | Stinging nettle | Cnidarians | Nematocysts (stinging cells) | 7004160000000000000♠approx. 16,000[13] |

Ctenophora | Comb bearer | Comb jellies[15]:256 | Eight "comb rows" of fused cilia | 7002100000000000000♠approx. 100-150 extant |

Cycliophora | Wheel carrying | Symbion | Circular mouth surrounded by small cilia, sac-like bodies | 7000300000000000000♠3+ |

Echinodermata | Spiny skin | Echinoderms[15]:348 | Fivefold radial symmetry in living forms, mesodermal calcified spines | 7003750000000000000♠approx. 7,500 extant;[13] approx. 13,000 extinct |

Entoprocta | Inside anus[15]:292 | Goblet worms | Anus inside ring of cilia | 7002150000000000000♠approx. 150 |

Gastrotricha | Hairy stomach[15]:288 | Gastrotrich worms | Two terminal adhesive tubes | 7002690000000000000♠approx. 690 |

Gnathostomulida | Jaw orifice | Jaw worms[15]:260 | 7002100000000000000♠approx. 100 | |

Hemichordata | Half cord[15]:344 | Acorn worms, hemichordates | Stomochord in collar, pharyngeal slits | 7002130000000000000♠approx. 130 extant |

Kinorhyncha | Motion snout | Mud dragons | Eleven segments, each with a dorsal plate | 7002150000000000000♠approx. 150 |

Loricifera | Corset bearer | Brush heads | Umbrella-like scales at each end | 7002122000000000000♠approx. 122 |

Micrognathozoa | Tiny jaw animals | Limnognathia | Accordion-like extensible thorax | 7000100000000000000♠1 |

Mollusca | Soft[15]:320 | Mollusks / molluscs | Muscular foot and mantle round shell | 7004850000000000000♠85,000+ extant;[13] 80,000+ extinct[16] |

Nematoda | Thread like | Round worms, thread worms[15]:274 | Round cross section, keratin cuticle | 7004250000000000000♠25,000[13] |

Nematomorpha | Thread form[15]:276 | Horsehair worms, Gordian worms[15]:276 | 7002320000000000000♠approx. 320 | |

Nemertea | A sea nymph[15]:270 | Ribbon worms, Rhynchocoela[15]:270 | 7003120000000000000♠approx. 1,200 | |

Onychophora | Claw bearer | Velvet worms[15]:328 | Legs tipped by chitinous claws | 7002200000000000000♠approx. 200 extant |

Orthonectida | Straight swimming[15]:268 | Orthonectids[15]:268 | Single layer of ciliated cells surrounding a mass of sex cells | 7001260000000000000♠approx. 26 |

Phoronida | Zeus's mistress | Horseshoe worms | U-shaped gut | 7001110000000000000♠11 |

Placozoa | Plate animals | Trichoplaxes[15]:242 | Differentiated top and bottom surfaces, two ciliated cell layers, amoeboid fiber cells in between | 7000100000000000000♠1 |

Platyhelminthes | Flat worm[15]:262 | Flatworms[15]:262 | 7004295000000000000♠approx. 29,500[13] | |

Porifera [a] | Pore bearer | Sponges[15]:246 | Perforated interior wall | 7004108000000000000♠10,800 extant[13] |

Priapulida | Little Priapus | Penis worms | 7001200000000000000♠approx. 20 | |

Rhombozoa | Lozenge animal | Rhombozoans[15]:264 | Single anteroposterior axial cell surrounded by ciliated cells | 7002100000000000000♠100+ |

Rotifera | Wheel bearer | Rotifers[15]:282 | Anterior crown of cilia | 7003200000000000000♠approx. 2,000[13] |

Sipuncula | Small tube | Peanut worms | Mouth surrounded by invertible tentacles | 144-320 |

Tardigrada | Slow step | Water bears | Four segmented body and head | 1,000 |

Xenacoelomorpha | Strange form without gut | — | Ciliated deuterostome | 7002400000000000000♠400+ |

Total: 35 | 1,525,000[13] |

Plants

The kingdom Plantae is defined in various ways by different biologists (see Current definitions of Plantae). All definitions include the living embryophytes (land plants), to which may be added the two green algae divisions, Chlorophyta and Charophyta, to form the clade Viridiplantae. The table below follows the influential (though contentious) Cavalier-Smith system in equating "Plantae" with Archaeplastida,[17] a group containing Viridiplantae and the algal Rhodophyta and Glaucophyta divisions.

The definition and classification of plants at the division level also varies from source to source, and has changed progressively in recent years. Thus some sources place horsetails in division Arthrophyta and ferns in division Pteridophyta,[18] while others place them both in Pteridophyta, as shown below. The division Pinophyta may be used for all gymnosperms (i.e. including cycads, ginkgos and gnetophytes),[19] or for conifers alone as below.

Since the first publication of the APG system in 1998, which proposed a classification of angiosperms up to the level of orders, many sources have preferred to treat ranks higher than orders as informal clades. Where formal ranks have been provided, the traditional divisions listed below have been reduced to a very much lower level, e.g. subclasses.[20]

Land plants | Viridiplantae | |

Green algae | ||

| Other algae (Biliphyta)[17] | ||

| Division | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics | Species described |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Anthocerotophyta[21] | Anthoceros-like plant | Hornworts | Horn-shaped sporophytes, no vascular system | 7002100000000000000♠100-300+ |

Bryophyta[22] | Bryum-like plant, moss plant | Mosses | Persistent unbranched sporophytes, no vascular system | 7004120000000000000♠approx. 12,000 |

Charophyta | Chara-like plant | Charophytes | 7003100000000000000♠approx. 1,000 | |

Chlorophyta | Yellow-green plant[15]:200 | Chlorophytes | 7003700000000000000♠approx. 7,000 | |

Cycadophyta[23] | Cycas-like plant, palm-like plant | Cycads | Seeds, crown of compound leaves | 7002100000000000000♠approx. 100-200 |

Ginkgophyta[24] | Ginkgo-like plant | Ginkgo, maidenhair tree | Seeds not protected by fruit (single living species) | 7000100000000000000♠only 1 extant; 50+ extinct |

Glaucophyta | Blue-green plant | Glaucophytes | 7001130000000000000♠13 | |

Gnetophyta[25] | Gnetum-like plant | Gnetophytes | Seeds and woody vascular system with vessels | 7001700000000000000♠approx. 70 |

Lycopodiophyta,[19] Lycophyta[26] | Lycopodium-like plant Wolf plant | Clubmosses & spikemosses | Microphyll leaves, vascular system | 7003129000000000000♠1,290 extant |

Magnoliophyta | Magnolia-like plant | Flowering plants, angiosperms | Flowers and fruit, vascular system with vessels | 7005300000000000000♠300,000 |

Marchantiophyta,[27] Hepatophyta[22] | Marchantia-like plant Liver plant | Liverworts | Ephemeral unbranched sporophytes, no vascular system | 7003900000000000000♠approx. 9,000 |

Pinophyta,[19] Coniferophyta[28] | Pinus-like plant Cone-bearing plant | Conifers | Cones containing seeds and wood composed of tracheids | 7002629000000000000♠629 extant |

Pteridophyta[citation needed] | Pteris-like plant, fern plant | Ferns & horsetails | Prothallus gametophytes, vascular system | 7003900000000000000♠approx. 9,000 (not including lycophytes) |

Rhodophyta | Rose plant | Red algae | 7003700000000000000♠approx. 7,000 | |

Total: 14 |

Fungi

| Division | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

Ascomycota | Bladder fungus[15]:396 | Ascomycetes,[15]:396 sac fungi | |

Basidiomycota | Small base fungus[15]:402 | Basidiomycetes[15]:402 | |

Blastocladiomycota | Offshoot branch fungus[29] | Blastoclads | |

Chytridiomycota | Little cooking pot fungus[30] | Chytrids | |

Glomeromycota | Ball of yarn fungus[15]:394 | Glomeromycetes, AM fungi[15]:394 | |

Microsporidia | Small seeds[31] | Microsporans[15]:390 | |

Neocallimastigomycota | New beautiful whip fungus[32] | Neocallimastigomycetes | |

Zygomycota | Pair fungus[15]:392 | Zygomycetes[15]:392 | |

Total: 8 |

Phylum Microsporidia is generally included in kingdom Fungi, though its exact relations remain uncertain,[33] and it is considered a protozoan by the International Society of Protistologists[34] (see Protista, below). Molecular analysis of Zygomycota has found it to be polyphyletic (its members do not share an immediate ancestor),[35] which is considered undesirable by many biologists. Accordingly, there is a proposal to abolish the Zygomycota phylum. Its members would be divided between phylum Glomeromycota and four new subphyla incertae sedis (of uncertain placement): Entomophthoromycotina, Kickxellomycotina, Mucoromycotina, and Zoopagomycotina.[33]

Protista

Kingdom Protista (or Protoctista) is included in the traditional five- or six-kingdom model, where it can be defined as containing all eukaryotes that are not plants, animals, or fungi.[15]:120 Protista is a polyphyletic taxon[36] (it includes groups not directly related to one another), which is less acceptable to present-day biologists than in the past. Proposals have been made to divide it among several new kingdoms, such as Protozoa and Chromista in the Cavalier-Smith system.[37]

Protist taxonomy has long been unstable,[38] with different approaches and definitions resulting in many competing classification schemes. The phyla listed here are used for Chromista and Protozoa by the Catalogue of Life,[39] adapted from the system used by the International Society of Protistologists.[34]

Chromista | |

Protozoa |

| Phylum/Division | Meaning | Common name | Distinguishing characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Amoebozoa | Amorphous animal | Amoebas | Amoeba | |

Bigyra | Two ring | |||

Cercozoa | ||||

Choanozoa | Funnel animal | |||

Ciliophora | Cilia bearer | Ciliates | Paramecium | |

Cryptista | ||||

Euglenozoa | True eye animal | Euglena | ||

Foraminifera | Hole bearers | Forams | Complex shells with one or more chambers | Forams |

Haptophyta | ||||

Loukozoa | Groove animal | |||

Metamonada | Giardia | |||

Microsporidia | Small spore | |||

Myzozoa | Suckling animal | |||

Mycetozoa | Slime molds | |||

Ochrophyta | Yellow plant | Diatoms | Diatoms | |

Oomycota | Egg fungus[15]:184 | Oomycetes | ||

Percolozoa | ||||

Radiozoa | Ray animal | Radiolarians | ||

Sarcomastigophora | ||||

Sulcozoa | ||||

Total: 20 |

The Catalogue of Life includes Rhodophyta and Glaucophyta in kingdom Plantae,[39] but other systems consider these phyla part of Protista.[40]

Bacteria

Currently there are 29 phyla accepted by List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[41]

Acidobacteria, phenotipically diverse and mostly uncultured

Actinobacteria, High-G+C Gram positive species

Aquificae, only 14 thermophilic genera, deep branching- Armatimonadetes

- Bacteroidetes

Caldiserica, formerly candidate division OP5, Caldisericum exile is the sole representative

Chlamydiae, only 6 genera

Chlorobi, only 7 genera, green sulphur bacteria

Chloroflexi, green non-sulphur bacteria

Chrysiogenetes, only 3 genera (Chrysiogenes arsenatis, Desulfurispira natronophila, Desulfurispirillum alkaliphilum)

Cyanobacteria, also known as the blue-green algae- Deferribacteres

Deinococcus-Thermus, Deinococcus radiodurans and Thermus aquaticus are "commonly known" species of this phyla- Dictyoglomi

Elusimicrobia, formerly candidate division Thermite Group 1- Fibrobacteres

Firmicutes, Low-G+C Gram positive species, such as the spore-formers Bacilli (aerobic) and Clostridia (anaerobic)- Fusobacteria

- Gemmatimonadetes

Lentisphaerae, formerly clade VadinBE97- Nitrospira

- Planctomycetes

Proteobacteria, the most known phyla, containing species such as Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Spirochaetes, species include Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease- Synergistetes

Tenericutes, alternatively class Mollicutes in phylum Firmicutes (notable genus: Mycoplasma)- Thermodesulfobacteria

Thermotogae, deep branching- Verrucomicrobia

Archaea

Currently there are 5 phyla accepted by List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN).[41]

Crenarchaeota, second most common archaeal phylum

Euryarchaeota, most common archaeal phylum- Korarchaeota

Nanoarchaeota, ultra-small symbiotes, single known species- Thaumarchaeota

See also

- Cladistics

- Phylogenetics

- Systematics

- Taxonomy

Notes

^ Paraphyletic

References

^ ab McNeill, J.; et al., eds. (2012). International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code), Adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011 (electronic ed.). International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Retrieved 2017-05-14..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Life sciences". The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy (third ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-04.Phyla in the plant kingdom are frequently called divisions.

^ Berg, Linda R. (2 March 2007). Introductory Botany: Plants, People, and the Environment (2 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 15. ISBN 9780534466695. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

^ Valentine 2004, p. 8.

^ Naik, V.N. (1984). Taxonomy of Angiosperms. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 27. ISBN 9780074517888.

^ Collins AG, Valentine JW (2001). "Defining phyla: evolutionary pathways to metazoan body plans." Evol. Dev. 3: 432-442.

^ Valentine, James W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.Classifications of organisms in hierarchical systems were in use by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Usually organisms were grouped according to their morphological similarities as perceived by those early workers, and those groups were then grouped according to their similarities, and so on, to form a hierarchy.

^ abcde Budd, G.E.; Jensen, S. (May 2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews. 75 (2): 253–295. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x. PMID 10881389. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

^ Rouse G.W. (2001). "A cladistic analysis of Siboglinidae Caullery, 1914 (Polychaeta, Annelida): formerly the phyla Pogonophora and Vestimentifera". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 132 (1): 55–80. doi:10.1006/zjls.2000.0263.

^ Pawlowski J, Montoya-Burgos JI, Fahrni JF, Wüest J, Zaninetti L (October 1996). "Origin of the Mesozoa inferred from 18S rRNA gene sequences". Mol. Biol. Evol. 13 (8): 1128–32. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025675. PMID 8865666.

^ Budd, G. E. (September 1998). "Arthropod body-plan evolution in the Cambrian with an example from anomalocaridid muscle". Lethaia. 31 (3): 197–210. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1998.tb00508.x.

^ Briggs, D. E. G.; Fortey, R. A. (2005). "Wonderful strife: systematics, stem groups, and the phylogenetic signal of the Cambrian radiation". Paleobiology. 31 (2 (Suppl)): 94–112. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0094:WSSSGA]2.0.CO;2.

^ abcdefghijkl Zhang, Zhi-Qiang (2013-08-30). "Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013)". Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 5. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3.

^ Felder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. (2009). Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity. Texas A&M University Press. p. 1111. ISBN 978-1-60344-269-5.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakal Margulis, Lynn; Chapman, Michael J. (2009). Kingdoms and Domains (4th corrected ed.). London: Academic Press. ISBN 9780123736215.

^ Feldkamp, S. (2002) Modern Biology. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, USA. (pp. 725)

^ ab Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (22 June 2004). "Only Six Kingdoms of Life". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 271 (1545): 1251–1262. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705. PMC 1691724. PMID 15306349.

^ Mauseth 2012, pp. 514, 517.

^ abc Cronquist, A.; A. Takhtajan; W. Zimmermann (April 1966). "On the higher taxa of Embryobionta". Taxon. 15 (4): 129–134. doi:10.2307/1217531. JSTOR 1217531.

^ Chase, Mark W. & Reveal, James L. (October 2009), "A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161 (2): 122–127, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x

^ Mauseth, James D. (2012). Botany : An Introduction to Plant Biology (5th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-6580-7. p. 489

^ ab Mauseth 2012, p. 489.

^ Mauseth 2012, p. 540.

^ Mauseth 2012, p. 542.

^ Mauseth 2012, p. 543.

^ Mauseth 2012, p. 509.

^ Crandall-Stotler, Barbara; Stotler, Raymond E. (2000). "Morphology and classification of the Marchantiophyta". In A. Jonathan Shaw & Bernard Goffinet (Eds.). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-66097-6.CS1 maint: Uses editors parameter (link)

^ Mauseth 2012, p. 535.

^ Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (1 October 2016). "Blastocladiomycota". Diversity of Life. Susquehanna University. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

^ Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (9 January 2014). "Chytridiomycota". Diversity of Life. Susquehanna University. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

^ Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (12 March 2013). "Microsporidia". Diversity of Life. Susquehanna University. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

^ Holt, Jack R.; Iudica, Carlos A. (23 April 2013). "Neocallimastigomycota". Diversity of Life. Susquehanna University. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

^ ab Hibbett DS, Binder M, Bischoff JF, Blackwell M, Cannon PF, Eriksson OE, et al. (May 2007). "A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi" (PDF). Mycological Research. 111 (Pt 5): 509–47. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.626.9582. doi:10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004. PMID 17572334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

^ ab Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; et al. (29 April 2015). "A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms". PLOS One. 10 (6): e0119248. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

^ White, Merlin M.; James, Timothy Y.; O'Donnell, Kerry; et al. (Nov–Dec 2006). "Phylogeny of the Zygomycota Based on Nuclear Ribosomal Sequence Data". Mycologia. 98 (6): 872–884. doi:10.1080/15572536.2006.11832617.

^ Hagen, Joel B. (January 2012). "Five Kingdoms, More or Less: Robert Whittaker and the Broad Classification of Organisms". BioScience. 62 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.11.

^ Blackwell, Will H.; Powell, Martha J. (June 1999). "Reconciling Kingdoms with Codes of Nomenclature: Is It Necessary?". Systematic Biology. 48 (2): 406–412. doi:10.1080/106351599260382.

^ Davis, R. A. (19 March 2012). "Kingdom PROTISTA". College of Mount St. Joseph. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

^ ab "Taxonomic tree". Catalogue of Life. 23 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

^ Corliss, John O. (1984). "The Kingdom Protista and its 45 Phyla". BioSystems. 17 (2): 87–176. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(84)90003-0.

^ ab J.P. Euzéby. "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature: Phyla". Retrieved 2016-12-28.

External links

| Look up Phylum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Are phyla "real"? Is there really a well-defined "number of animal phyla" extant and in the fossil record?

- Major Phyla Of Animals