Proton decay

The pattern of weak isospins, weak hypercharges, and color charges for particles in the Georgi–Glashow model. Here, a proton, consisting of two up quarks and a down, decays into a pion, consisting of an up and anti-up, and a positron, via an X boson with electric charge −4/3.

In particle physics, proton decay is a hypothetical form of particle decay in which the proton decays into lighter subatomic particles, such as a neutral pion and a positron.[1] The proton decay hypothesis was first formulated by Andrei Sakharov in 1967. Despite significant experimental effort, proton decay has never been observed. If it does decay via a positron, the proton's half-life is constrained to be at least 7034166999999999999♠1.67×1034 years.[2]

According to the Standard Model, protons, a type of baryon, are stable because baryon number (quark number) is conserved (under normal circumstances; see chiral anomaly for exception). Therefore, protons will not decay into other particles on their own, because they are the lightest (and therefore least energetic) baryon. Positron emission – a form of radioactive decay which sees a proton become a neutron – is not proton decay, since the proton interacts with other particles within the atom.

Some beyond-the-Standard Model grand unified theories (GUTs) explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, allowing protons to decay via the Higgs particle, magnetic monopoles, or new X bosons with a half-life of 1031 to 1036 years. To date, all attempts to observe new phenomena predicted by GUTs (like proton decay or the existence of magnetic monopoles) have failed.

Quantum gravity (via virtual black holes and Hawking radiation) may also provide a venue of proton decay at magnitudes or lifetimes well beyond the GUT scale decay range above, as well as extra dimensions in supersymmetry.

There are theoretical methods of baryon violation other than proton decay including interactions with changes of baryon and/or lepton number other than 1 (as required in proton decay). These included B and/or L violations of 2, 3, or other numbers, or B − L violation. Such examples include neutron oscillations and the electroweak sphaleron anomaly at high energies and temperatures that can result between the collision of protons into antileptons[3] or vice versa (a key factor in leptogenesis and non-GUT baryogenesis).

Contents

1 Baryogenesis

2 Experimental evidence

3 Theoretical motivation

4 Projected proton lifetimes

5 Decay operators

5.1 Dimension-6 proton decay operators

5.2 Dimension-5 proton decay operators

5.3 Dimension-4 proton decay operators

6 Proton decay in media

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Baryogenesis

Unsolved problem in physics: Do protons decay? If so, then what is the half-life? Can nuclear binding energy affect this? (more unsolved problems in physics) |

One of the outstanding problems in modern physics is the predominance of matter over antimatter in the universe. The universe, as a whole, seems to have a nonzero positive baryon number density – that is, matter exists. Since it is assumed in cosmology that the particles we see were created using the same physics we measure today, it would normally be expected that the overall baryon number should be zero, as matter and antimatter should have been created in equal amounts. This has led to a number of proposed mechanisms for symmetry breaking that favour the creation of normal matter (as opposed to antimatter) under certain conditions. This imbalance would have been exceptionally small, on the order of 1 in every 7010100000000000000♠10000000000 (1010) particles a small fraction of a second after the Big Bang, but after most of the matter and antimatter annihilated, what was left over was all the baryonic matter in the current universe, along with a much greater number of bosons. Experiments reported in 2010 at Fermilab, however, seem to show that this imbalance is much greater than previously assumed. In an experiment involving a series of particle collisions, the amount of generated matter was approximately 1% larger than the amount of generated antimatter. The reason for this discrepancy is yet unknown.[4]

Most grand unified theories explicitly break the baryon number symmetry, which would account for this discrepancy, typically invoking reactions mediated by very massive X bosons (

X

) or massive Higgs bosons (

H0

). The rate at which these events occur is governed largely by the mass of the intermediate

X

or

H0

particles, so by assuming these reactions are responsible for the majority of the baryon number seen today, a maximum mass can be calculated above which the rate would be too slow to explain the presence of matter today. These estimates predict that a large volume of material will occasionally exhibit a spontaneous proton decay.

Experimental evidence

Proton decay is one of the key predictions of the various grand unified theories (GUTs) proposed in the 1970s, another major one being the existence of magnetic monopoles. Both concepts have been the focus of major experimental physics efforts since the early 1980s. To date, all attempts to observe these events have failed; however, these experiments have been able to establish lower bounds on the half-life of the proton. Currently the most precise results come from the Super-Kamiokande water Cherenkov radiation detector in Japan: a 2015 analysis placed a lower bound on the proton's half-life of 7034166999999999999♠1.67×1034 years via positron decay,[2] and similarly, a 2012 analysis gave a lower bound to the proton's half-life of 7034107999999999999♠1.08×1034 years via antimuon decay,[5] close to a supersymmetry (SUSY) prediction of 1034–1036 years.[6] An upgraded version, Hyper-Kamiokande, probably will have sensitivity 5–10 times better than Super-Kamiokande.[2]

Theoretical motivation

Despite the lack of observational evidence for proton decay, some grand unification theories, such as the SU(5) Georgi–Glashow model and SO(10), along with their supersymmetric variants, require it. According to such theories, the proton has a half-life of about 1031 to 1036 years and decays into a positron and a neutral pion that itself immediately decays into 2 gamma ray photons:

p+ | → | e+ | + | π0 |

π0 | → | 2 γ |

Since a positron is an antilepton this decay preserves B − L number, which is conserved in most GUTs.

Additional decay modes are available (e.g.:

p+

→

μ+

+

π0

),[5] both directly and when catalyzed via interaction with GUT-predicted magnetic monopoles.[7] Though this process has not been observed experimentally, it is within the realm of experimental testability for future planned very large-scale detectors on the megaton scale. Such detectors include the Hyper-Kamiokande.

Early grand unification theories (GUTs) such as the Georgi–Glashow model, which were the first consistent theories to suggest proton decay, postulated that the proton's half-life would be at least 1031 years. As further experiments and calculations were performed in the 1990s, it became clear that the proton half-life could not lie below 1032 years. Many books from that period refer to this figure for the possible decay time for baryonic matter. More recent findings have pushed the minimum proton half-life to at least 1034-1035 years, ruling out the simpler GUTs (including minimal SU(5)/Georgi–Glashow) and most non-SUSY models. The maximum upper limit on proton lifetime (if unstable), is calculated at 6 × 1039 years, a bound applicable to SUSY models,[8] with a maximum for (minimal) non-SUSY GUTs at 1.4 × 1036 years.[9]

Although the phenomenon is referred to as "proton decay", the effect would also be seen in neutrons bound inside atomic nuclei. Free neutrons—those not inside an atomic nucleus—are already known to decay into protons (and an electron and an antineutrino) in a process called beta decay. Free neutrons have a half-life of about 10 minutes (7002610200000000000♠610.2±0.8 s)[10] due to the weak interaction. Neutrons bound inside a nucleus have an immensely longer half-life—apparently as great as that of the proton.

Projected proton lifetimes

| Theory class | Proton lifetime (years)[11] |

|---|---|

| Minimal SU(5) (Georgi–Glashow) | 1030–1031 |

| Minimal SUSY SU(5) | 1028–1032 |

SUGRA SU(5) | 1032–1034 |

| SUSY SU(5)(MSSM) | ~1034 |

| Minimal (Basic) SO(10) – Non-SUSY | < ~1035 (maximum range) |

| SUSY SO(10) | 1032–1035 |

| SUSY SO(10) MSSM G(224) | 2·1034 |

Flipped SU(5) (MSSM) | 1035–1036 |

| SUSY SU(5) – 5 dimensions | 1034–1035 |

Decay operators

Dimension-6 proton decay operators

The dimension-6 proton decay operators are qqqlΛ2{displaystyle {frac {qqql}{Lambda ^{2}}}}

In GUT models, the exchange of an X or Y boson with the mass ΛGUT can lead to the last two operators suppressed by 1ΛGUT2{displaystyle {frac {1}{Lambda _{GUT}^{2}}}}

- Proton decay. These graphics refer to the X bosons and Higgs bosons.

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the

X boson (3,2)

−5⁄6 in SU(5) GUT

Dimension 6 proton decay mediated by the

X boson (3,2)

1⁄6 in flipped SU(5) GUT

Dimension-6 proton decay mediated by the

triplet Higgs T (3,1)

−1⁄3 and the

anti-triplet Higgs T (3,1)

1⁄3 in SU(5) GUT

Dimension-5 proton decay operators

In supersymmetric extensions (such as the MSSM), we can also have dimension-5 operators involving two fermions and two sfermions caused by the exchange of a tripletino of mass M. The sfermions will then exchange a gaugino or Higgsino or gravitino leaving two fermions. The overall Feynman diagram has a loop (and other complications due to strong interaction physics). This decay rate is suppressed by 1MMSUSY{displaystyle {frac {1}{MM_{SUSY}}}}

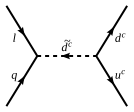

Dimension-4 proton decay operators

In the absence of matter parity, supersymmetric extensions of the Standard Model can give rise to the last operator suppressed by the inverse square of sdown quark mass. This is due to the dimension-4 operators

q

ℓ

d͂

c and

u

c

d

c

d͂

c.

The proton decay rate is only suppressed by 1MSUSY2{displaystyle {frac {1}{M_{SUSY}^{2}}}}

Proton decay in media

When Woody Allen in his 1980 film Stardust Memories launches a depressive soliloquy with the quote, "Did anybody read on the front page of The Times that matter is decaying?", this was almost certainly a reference to the GUTs models of the 1970s, given the film's period, their importance at the time and the many contemporary layperson articles in general media about some of the model's most striking consequences, particularly its mechanism for proton decay.

In the Law & Order episode "Big Bang", a scientist's pursuit of evidence that proton decay exists leads to the murder central to the episode.

In the Big Bang Theory episode "The Anxiety Optimization", Sheldon has a problem in his dark matter proton decay research.

In the Jerry Spinelli novel Smiles to Go, the notion of proton decay is a key source of anxiety for the book's protagonist.

See also

- Virtual black hole

- Weak hypercharge

- B − L

- X and Y bosons

- Age of the universe

References

^ Radioactive decays by Protons. Myth or reality?, Ishfaq Ahmad, The Nucleus, 1969. pp 69–70

^ abc Bajc, Borut; Hisano, Junji; Kuwahara, Takumi; Omura, Yuji (2016). "Threshold corrections to dimension-six proton decay operators in non-minimal SUSY SU(5) GUTs". Nuclear Physics B. 910: 1. arXiv:1603.03568. Bibcode:2016NuPhB.910....1B. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2016.06.017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Bloch Wave Function for the Periodic Sphaleron Potential and Unsuppressed Baryon and Lepton Number Violating Processes", S.H. Henry Tyne & Sam S.C. Wong. (2015). Phys. Rev. D, 92(4), 045005 (2015-08-05). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.92.045005

^

V.M. Abazov; et al. (2010). "Evidence for an anomalous like-sign dimuon charge asymmetry". Physical Review D. 82 (3): 032001. arXiv:1005.2757. Bibcode:2010PhRvD..82c2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.82.032001.

^ ab

H. Nishino; Super-K Collaboration (2012). "Search for Proton Decay via

p+

→

e+

π0

and

p+

→

μ+

π0

in a Large Water Cherenkov Detector". Physical Review Letters. 102 (14): 141801. arXiv:0903.0676. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102n1801N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.141801. PMID 19392425.

^ "Proton lifetime is longer than 1034 years". www-sk.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp. 25 November 2009.

^

B. V. Sreekantan (1984). "Searches for Proton Decay and Superheavy Magnetic Monopoles" (PDF). Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy. 5 (3): 251–271. Bibcode:1984JApA....5..251S. doi:10.1007/BF02714542.

^ Nath, Pran; Fileviez Pérez, Pavel (2007). "Proton stability in grand unified theories, in strings and in branes". Physics Reports. 441 (5–6): 191–317. arXiv:hep-ph/0601023. Bibcode:2007PhR...441..191N. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.010.

^ Nath and Perez, 2007, part 5.6

^

K.A. Olive; et al. (2014). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 38 (9): 090001. arXiv:astro-ph/0601168. Bibcode:2006JPhG...33....1Y. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/38/9/090001.

^ "Grand Unified Theories and Proton Decay", Ed Kearns, Boston University, 2009, page 15. http://physics.bu.edu/NEPPSR/TALKS-2009/Kearns_GUTs_ProtonDecay.pdf

Further reading

C. Amsler; Particle Data Group (2008). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Physics Letters B. 667 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:2008PhLB..667....1A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

K. Hagiwara; Particle Data Group (2002). "Review of Particle Physics – N Baryons" (PDF). Physical Review D. 66 (1): 010001. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..66a0001H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.66.010001.

F. Adams; G. Laughlin (2000-06-19). The Five Ages of the Universe : Inside the Physics of Eternity. ISBN 978-0-684-86576-8.

L.M. Krauss (2001). Atom : An Odyssey from the Big Bang to Life on Earth. ISBN 978-0-316-49946-0.

D.-D. Wu; T.-Z. Li (1985). "Proton decay, annihilation or fusion?". Zeitschrift für Physik C. 27 (2): 321–323. Bibcode:1985ZPhyC..27..321W. doi:10.1007/BF01556623.

P. Nath; P. Fileviez Perez (2007). "Proton stability in grand unified theories, in strings and in branes". Physics Reports. 441 (5–6): 191–317. arXiv:hep-ph/0601023. Bibcode:2007PhR...441..191N. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.010.

External links

- Proton decay at Super-Kamiokande

- Pictorial history of the IMB experiment

Luciano Maiani (8 February 2006). The problem of proton decay (PDF). Third NO-VE International Workshop on Neutrino Oscillations in Venice. Venice.