Liège

Liège Luik (Dutch) Lüttich (German) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Municipality | |||

Late-September 2009 aerial view of Liège | |||

| |||

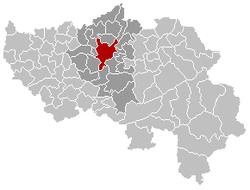

Liège Location in Belgium The municipality of Liège in the province of Liège  | |||

| Coordinates: 50°38′N 05°34′E / 50.633°N 5.567°E / 50.633; 5.567Coordinates: 50°38′N 05°34′E / 50.633°N 5.567°E / 50.633; 5.567 | |||

| Country | Belgium | ||

| Community | French Community | ||

| Region | Wallonia | ||

| Province | Liège | ||

| Arrondissement | Liège | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Willy Demeyer (PS) | ||

| • Governing party/ies | PS – cdH | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 69.39 km2 (26.79 sq mi) | ||

| Population (1 January 2017)[1] | |||

| • Total | 197,885 | ||

| • Density | 2,900/km2 (7,400/sq mi) | ||

| Postal codes | 4000–4032 | ||

| Area codes | 04 | ||

| Website | www.liege.be | ||

Liège (French: [ljɛʒ] (![]() listen) locally [li.eʃ]; Walloon: Lidje [liːtʃ]; Dutch: Luik, [lœyk] (

listen) locally [li.eʃ]; Walloon: Lidje [liːtʃ]; Dutch: Luik, [lœyk] (![]() listen); German: Lüttich) is a major Walloon city and municipality and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

listen); German: Lüttich) is a major Walloon city and municipality and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from borders with the Netherlands (Maastricht is about 33 km (20.5 mi) to the north) and with Germany (Aachen is about 53 km (32.9 mi) north-east). At Liège, the Meuse meets the River Ourthe. The city is part of the sillon industriel, the former industrial backbone of Wallonia. It still is the principal economic and cultural centre of the region.

The Liège municipality (i.e. the city proper) includes the former communes of Angleur, Bressoux, Chênée, Glain, Grivegnée, Jupille-sur-Meuse, Rocourt, and Wandre. In November 2012, Liège had 198,280 inhabitants. The metropolitan area, including the outer commuter zone, covers an area of 1,879 km2 (725 sq mi) and had a total population of 749,110 on 1 January 2008.[2][3] This includes a total of 52 municipalities, among others, Herstal and Seraing. Liège ranks as the third most populous urban area in Belgium, after Brussels and Antwerp, and the fourth municipality after Antwerp, Ghent and Charleroi.[3]

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Early Middle Ages

2.2 Late Medieval and Early Modern Period

2.3 18th century to World War I

2.4 World War II to the present

3 Climate

4 Demographics

5 Main sights

6 Folklore

7 Culture

7.1 Sports

8 Economy

8.1 1812 mine accident

9 Transport

9.1 Air

9.2 Maritime

9.3 Rail

9.4 Road

10 Famous inhabitants

11 International relations

11.1 Twin towns – Sister cities

12 See also

13 References

14 Bibliography

15 External links

Etymology

The name is Germanic in origin and is reconstructible as *liudik-, from the Germanic word *liudiz "people", which is found in for example Dutch lui(den), lieden, German Leute, Old English lēod (English lede) and Icelandic lýður ("people"). It is found in Lithuanian as liaudis ("people"), in Russian as liudi ("people"), in Latin as Leodicum or Leodium, in Middle Dutch as ludic or ludeke.[4]

Until 17 September 1946, the city's name was written Liége, with the acute accent instead of a grave accent.[5][6][7]

In French, Liège is associated with the epithet la cité ardente ("the fervent city"). This term, which emerged around 1905, originally referred to the city's history of rebellions against Burgundian rule, but was appropriated to refer to its economic dynamism during the Industrial Revolution.[8]

History

Early Middle Ages

Although settlements already existed in Roman times, the first references to Liège are from 558, when it was known as Vicus Leudicus. Around 705, Saint Lambert of Maastricht is credited with completing the Christianization of the region, indicating that up to the early 8th century the religious practices of antiquity had survived in some form. Christian conversion may still not have been quite universal, since Lambert was murdered in Liège and thereafter regarded as a martyr for his faith. To enshrine St. Lambert's relics, his successor, Hubertus (later to become St. Hubert), built a basilica near the bishop's residence which became the true nucleus of the city. A few centuries later, the city became the capital of a prince-bishopric, which lasted from 985 till 1794. The first prince-bishop, Notger, transformed the city into a major intellectual and ecclesiastical centre, which maintained its cultural importance during the Middle Ages. Pope Clement VI recruited several musicians from Liège to perform in the Papal court at Avignon, thereby sanctioning the practice of polyphony in the religious realm. The city was renowned for its many churches, the oldest of which, St Martin's, dates from 682. Although nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, in practice it possessed a large degree of independence.

Late Medieval and Early Modern Period

Liège in 1650

The strategic position of Liège has made it a frequent target of armies and insurgencies over the centuries. It was fortified early on with a castle on the steep hill that overlooks the city's western side. During this medieval period, three women from the Liège region made significant contributions to Christian spirituality: Elizabeth Spaakbeek, Christina the Astonishing, and Marie of Oignies.[9]

In 1345, the citizens of Liège rebelled against Prince-Bishop Engelbert III de la Marck, their ruler at the time, and defeated him in battle near the city. Shortly after, a unique political system formed in Liège, whereby the city's 32 guilds shared sole political control of the municipal government. Each person on the register of each guild was eligible to participate, and each guild's voice was equal, making it the most democratic system that the Low Countries had ever known. The system spread to Utrecht, and left a democratic spirit in Liège that survived the Middle Ages.[10]

At the end of the Liège Wars, a rebellion against rule from Burgundy that figured prominently in the plot of Sir Walter Scott's 1823 novel Quentin Durward, Duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy, witnessed by King Louis XI of France, captured and largely destroyed the city in 1468, after a bitter siege which was ended with a successful surprise attack.

The Prince-Bishopric of Liège was technically part of the Holy Roman Empire which, after 1477, came under the rule of the Habsburgs. The reign of prince-bishop Erard de la Marck (1506–1538) coincides with the dawn of the Renaissance.

During the Counter-Reformation, the diocese of Liège was split and progressively lost its role as a regional power. In the 17th century, many prince-bishops came from the royal house of Wittelsbach. They ruled over Cologne and other bishoprics in the northwest of the Holy Roman Empire as well.

In 1636, during the Thirty Years' War, the city was besieged by Imperial forces under Johann von Werth from April to July. The army, mainly consisting of mercenaries, extensively and viciously plundered the surrounding bishopric during the siege.[11]

18th century to World War I

Liège in 1627

The Duke of Marlborough captured the city from the Bavarian prince-bishop and his French allies in 1704 during the War of the Spanish Succession.

In the middle of the eighteenth century the ideas of the French Encyclopédistes began to gain popularity in the region. Bishop de Velbruck (1772–84), encouraged their propagation, thus prepared the way for the Liège Revolution which started in the episcopal city on 18 August 1789 and led to the creation of the Republic of Liège before it was invaded by counter-revolutionary forces of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1791.

In the course of the 1794 campaigns of the French Revolution, the French army took the city and imposed strongly anticlerical regime, destroying St. Lambert's Cathedral. The overthrow of the prince-bishopric was confirmed in 1801 by the Concordat co-signed by Napoléon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII. France lost the city in 1815 when the Congress of Vienna awarded it to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Dutch rule lasted only until 1830, when the Belgian Revolution led to the establishment of an independent, Catholic and neutral Belgium which incorporated Liège. After this, Liège developed rapidly into a major industrial city which became one of continental Europe's first large-scale steel making centres. The Walloon Jacquerie of 1886 saw a large-scale working class revolt.[12] No less than 6,000 regular troops were called into the city to quell the unrest,[13] while strike spread through the whole sillon industriel.

St. Lambert's Cathedral and the palace of the Prince-Bishops in 1770

Quai de la Goffe

Liège's fortifications were redesigned by Henri Alexis Brialmont in the 1880s and a chain of twelve forts was constructed around the city to provide defence in depth. This presented a major obstacle to Germany's army in 1914, whose Schlieffen Plan relied on being able to quickly pass through the Meuse valley and the Ardennes en route to France. The German invasion on 5 August 1914 soon reached Liège, which was defended by 30,000 troops under General Gérard Leman (see Battle of Liège). The forts initially held off an attacking force of about 100,000 men but were pulverised into submission by a five-day bombardment by heavy artillery, including thirty-two 21 cm mortars and two German 42 cm Big Bertha howitzers. Due to faulty planning of the protection of the underground defense tunnels beneath the main citadel, one direct artillery hit caused a huge explosion, which eventually led to the surrender of the Belgian forces. The Belgian resistance was shorter than had been intended, but the twelve days of delay caused by the siege nonetheless contributed to the eventual failure of the German invasion of France. The city was subsequently occupied by the Germans until the end of the war. Liège received the Légion d'Honneur for its resistance in 1914.

World War II to the present

Inauguration of the statue of Charlemagne, 26 July 1868

The Germans returned in 1940, this time taking the forts in only three days. Most Jews were saved, with the help of the sympathetic population, as many Jewish children and refugees were hidden in the numerous monasteries. Liege was liberated by the British military in September of 1944.[14]

After the war ended, the Royal Question came to the fore, since many saw King Leopold III as collaborating with the Germans during the war. In July 1950, André Renard, leader of the Liégeois FGTB launched the General strike against Leopold III of Belgium and "seized control over the city of Liège".[15] The strike ultimately led to Leopold's abdication.

Liège began to suffer from a relative decline of its industry, particularly the coal industry, and later the steel industry, producing high levels of unemployment and stoking social tension. During the 1960-1961 Winter General Strike, disgruntled workers went on a rampage and severely damaged the central railway station Guillemins. The unrest was so intense that "army troops had to wade through caltrops, trees, concrete blocks, car and crane wrecks to advance. Streets were dug up. Liège saw the worst fighting on 6 January 1961. In all, 75 people were injured during seven hours of street battles."[16]

On 6 December 1985, the city's courthouse was heavily damaged and one person was killed in a bomb attack by a lawyer.

Liège is also known as a traditionally socialist city. In 1991, powerful Socialist André Cools, a former Deputy Prime Minister, was gunned down in front of his girlfriend's apartment. Many suspected that the assassination was related to a corruption scandal which swept the Socialist Party, and the national government in general, after Cools' death. Two men were sentenced to twenty years in jail in 2004, for involvement in Cools' murder.

Liège has shown some signs of economic recovery in recent years with the opening up of borders within the European Union, surging steel prices, and improved administration. Several new shopping centres have been built, and numerous repairs carried out.

On 13 December 2011, there was a grenade and gun attack at Place Saint-Lambert. An attacker, later identified as Nordine Amrani, aged 33, armed with grenades and an assault rifle, attacked people waiting at a bus stop. There were six fatalities, including the attacker (who shot himself), and 123 people were injured.[17]

On 29 May 2018, two female police officers and one civilian—a 22-year-old man—were shot dead by a gunman near a café on Boulevard d'Avroy in central Liège. The attacker then began firing at the officers in an attempt to escape, injuring a number of them "around their legs", before he was shot dead. Belgian broadcaster RTBF said the gunman was temporarily released from prison on 28 May where he had been serving time on drug offences. The incident is currently being treated as terrorism.[18]

Climate

In spite of its inland position Liège has a maritime climate influenced by the mildening sea winds originating from the Gulf Stream, travelling over Belgium's interior. As a result, Liège has very mild winters for its latitude and inland position, especially compared to areas in the Russian Far East and fellow Francophone province Quebec. Summers are also moderated by the maritime air, with average temperatures being similar to areas as far north as in Scandinavia. Being inland though, Liège has a relatively low seasonal lag compared to some other maritime climates.

| Climate data for Liège (1981–2010 normals, sunshine 1984–2013) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) | 6.2 (43.2) | 10.0 (50) | 13.8 (56.8) | 18.1 (64.6) | 20.7 (69.3) | 23.2 (73.8) | 22.9 (73.2) | 19.0 (66.2) | 14.6 (58.3) | 9.2 (48.6) | 5.8 (42.4) | 14.0 (57.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) | 2.9 (37.2) | 6.0 (42.8) | 8.9 (48) | 13.1 (55.6) | 15.8 (60.4) | 18.2 (64.8) | 17.7 (63.9) | 14.4 (57.9) | 10.7 (51.3) | 6.2 (43.2) | 3.3 (37.9) | 10 (50) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) | −0.3 (31.5) | 2.2 (36) | 4.1 (39.4) | 8.1 (46.6) | 10.9 (51.6) | 13.0 (55.4) | 12.5 (54.5) | 9.9 (49.8) | 6.9 (44.4) | 3.5 (38.3) | 0.8 (33.4) | 6 (42.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.4 (2.93) | 64.8 (2.55) | 71.2 (2.8) | 61.3 (2.41) | 73.1 (2.88) | 83.1 (3.27) | 78.7 (3.1) | 80.2 (3.16) | 71.6 (2.82) | 72.0 (2.83) | 70.1 (2.76) | 81.5 (3.21) | 882.0 (34.72) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.2 | 11.6 | 13.3 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 11.6 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 14.0 | 142.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56 | 77 | 118 | 165 | 193 | 188 | 201 | 191 | 139 | 114 | 61 | 43 | 1,545 |

| Source: Royal Meteorological Institute [19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

On 1 January 2013, the municipality of Liège had a total population of 197,013. The metropolitan area has about 750,000 inhabitants. Its inhabitants are predominantly French-speaking, with German and Dutch-speaking minorities. Like the rest of Belgium, the population of minorities has grown significantly since the 1990s. The city has become the home to large numbers of Moroccan, Algerian and Turkish immigrants.

The city is a major educational hub in Belgium. There are 42,000 pupils attending more than 24 schools. The University of Liège, founded in 1817, has 20,000 students.

Main sights

Panorama of the city of Liège. Photo taken from the heights of the Citadel (left bank of the River Meuse).

The stairway of the Montagne de Bueren.

The vast palace of the Prince-Bishops of Liège is built on the Place St Lambert, where the old St. Lambert's Cathedral used to stand before the French Revolution. The oldest rooms date from the 16th century. An archeological display, the Archéoforum, can be visited under the Place St Lambert.- The perron on the nearby Place du Marché was once the symbol of justice in the Prince-Bishopric and is now the symbol of the city. It stands in front of the 17th century city hall.

- The present Liège Cathedral, dedicated to Saint Paul, contains a treasury and Saint Lambert’s tomb. It is one of the original seven collegiate churches, which include the German-Romanesque St Bartholomew's Church (Saint Barthélémy) and the church of St Martin.

- The church of Saint-James (Saint-Jacques) is probably the most beautiful medieval church in Liège. It is built in the so-called Flamboyant-Gothic style, while the porch is early Renaissance. The statues are by Liège sculptor Jean Del Cour. Saint-Jacques also contains 29 spectacular 14th century misericords.

- The main museums in Liège are: MAMAC (Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art), Museum of Walloon Life, and Museum of Walloon Art & Religious Art (Mosan art). The Grand Curtius Museum is an elegantly furnished mansion from the 17th century along the Meuse River, housing collections of Egyptology, weaponry, archaeology, fine arts, religious art and Mosan art.

- Other sites of interest include the historical city centre (the Carré), the Hors-Château area, the Outremeuse area, the parks and boulevards along the River Meuse, the Citadel, the 374[20] steps stairway "Montagne de Bueren", leading from Hors-Château to the Citadel, 'Médiacité' shopping mall designed by Ron Arad Architects and the Liège-Guillemins railway station designed by Santiago Calatrava.

- Liège's pedestrian zone is the biggest pedestrian zone of the Walloon Region and the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion;[21] it is also the oldest in Belgium. The pedestrian zone progressively has grown since 1965 to contain the majority of the hypercentre of Liège. It continues to grow today with the addition of the Rue de la Casquette on 12 December 2014.[22]

Folklore

Traditional Liégeois puppets

The "Le Quinze Août" celebration takes place annually on 15 August in Outremeuse and celebrates the Virgin Mary. It is one of the biggest folkloric displays in the city, with a religious procession, a flea market, dances, concerts, and a series of popular games. Nowadays these celebrations start a few days earlier and last until the 16th. Some citizens open their doors to party goers, and serve "peket", the traditional local alcohol. This tradition is linked to the important folkloric character Tchantchès (Walloon for François), a hard-headed but resourceful Walloon boy who lived during Charlemagne's times. Tchantchès is remembered with a statue, a museum, and a number of puppets found all over the city.

Liège hosts one of the oldest and biggest Christmas Markets in Belgium.

Culture

Liège, the Sunday "Batte" market

The city is well known for its very crowded folk festivals. The 15 August festival ("Le 15 août") is maybe the best known. The population gathers in a quarter named Outre-Meuse with plenty of tiny pedestrian streets and old yards. Many people come to see the procession but also to drink alcohol (mostly peket) and beer, eat cooked pears, boûkètes or sausages or simply enjoy the atmosphere until the early hours.[23] The Saint Nicholas festival around 6 December is organized by and for the students of the University; for a few days before the event, students (wearing very dirty lab-coats) beg for money, mostly for drinking.[24][25][26]

Liège is renowned for its significant nightlife.[27] Within the pedestrian zone behind the Opera House, there is a square city block known locally as Le Carré (the Square) with many lively pubs which are reputed to remain open until the last customer leaves (typically around 6 am). Another active area is the Place du Marché.

The "Batte" market is where most locals visit on Sundays.[citation needed] The outdoor market goes along the Meuse River and also attracts many visitors to Liège. The market typically runs from early morning to 2 o'clock in the afternoon every Sunday year long. Produce, clothing, and snack vendors are the main concentration of the market.

Liège is home to the Opéra Royal de Wallonie (English: Royal Opera of Wallonia) and the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège (OPRL) (English: Liège Royal Philharmonic Orchestra).

The city annually hosts a significant electro-rock festival Les Ardentes and jazz festival Jazz à Liège.

Liège has active alternative cinemas, Le Churchill, Le Parc and Le Sauvenière. There are also 2 mainstream cinemas, the Kinepolis multiplexes.

Liège also has a particular Walloon dialect, sometimes said to be one of Belgium's most distinctive. There is a large Italian community, and Italian can be heard in many places.

Sports

Stade Maurice Dufrasne, home to football club Standard Liège.

The city has a number of football teams, most notably Standard Liège, who have won several championships and which was previously owned by Roland Duchâtelet, and R.F.C. de Liège, one of the oldest football clubs in Belgium. It is also known for being the club who refused to release Jean-Marc Bosman, a case which led to the Bosman ruling.

In spring, Liège hosts the start and finish of the annual Liège–Bastogne–Liège cycling race, one of the spring classics and the oldest of the five monuments of cycling. The race starts in the centre of Liège, before heading south to Bastogne and returning north to finish in the industrial suburb of Ans. Traveling through the hilly Ardennes, it is one of the longest and most arduous races of the season.[28]

Liège is the only city that has hosted stages of all three cycling Grand Tours. It staged the start of the 1973 and 2006 Giro d'Italia; as well as the Grand Départ of the 2004 and 2012 Tour de France,[29][30][31] making it the first city outside France to host the Grand Départ twice.[32] In 2009, the Vuelta a España visited Liège after four stages in the Netherlands, making Liège the first city that has hosted stages of all three cycling Grand Tours.[33] It will also host the finish of stage 2 of the 2017 Tour de France.[34]

Liège is also home to boxer Ermano Fegatilli, the current European Boxing Union Super Featherweight champion.[35]

Economy

Pont de Fragnée

Liège at night, photography taken from the ISS on December 2012[36]

Liège is the most important city of the Wallon region from an economic perspective. In the past, Liège was one of the most important industrial centres in Europe, particularly in steel-making. Starting in 1817, John Cockerill extensively developed the iron and steel industry. The industrial complex of Seraing was the largest in the world. It once boasted numerous blast furnaces and mills. Liège has also been an important centre for gunsmithing since the Middle ages and the arms industry is still strong today, with the headquarters of FN Herstal and CMI Defence being located in Liège. Although from 1960 on the secondary sector is going down and now is a mere shadow of its former self, the manufacture of steel goods remain important.

The economy of the region is now diversified; the most important centres are: Mechanical industries (Aircraft engine and Spacecraft propulsion), space technology, information technology, biotechnology and the production of water, beer or chocolate. Liège has an important group of headquarters dedicated to high-technology, such as Techspace Aero, which manufactures pieces for the Airbus A380 or the rocket Ariane 5. Other stand-out sectors include Amós which manufactures optical components for telescopes and Drytec, fabric of compressed air dryers. Liège also has many other electronic companies such as SAP, EVS, Gillam, AnB, Balteau, IP Trade. Other prominent businesses are the global leader in light armament FN Herstal, the beer company Jupiler, the chocolate company Galler, and the water and soda companies Spa and Chaudfontaine. A science park south east of the city, near the University of Liège campus, houses spin-offs and high technology businesses.

1812 mine accident

In 1812 there were three coal pits (Bure) in close proximity just outside the city gates: Bure Triquenotte, Bure de Beaujone and Bure Mamonster. The first two shafts were joined underground, but the last one was a separate colliery. The shafts were 120 fathoms (720 ft; 220 m) deep. Water was led to a sump (serrement) from which it could be pumped to the surface. At 11:00 on 28 February 1812 the sump in the Beaujone mine failed and flooded the entire colliery. Of the 127 men down the mine at the time 35 escaped by the main shaft, but 74 were trapped. [These numbers are taken from the report, the 18 miner discrepancy is unexplained.] The trapped men attempted to dig a passageway into Mamonster. After 23 feet (7.0 m) there was a firedamp explosion and they realised that they had penetrated some old workings belonging to an abandoned mine, Martin Wery. The overseer, Monsieur Goffin, led the men to the point in Martin Wery which he judged closest to Mamonster and they commence to dig. By the second day they had run out of candles and dug the remainder of a 36 feet (11 m) gallery in darkness.

On the surface the only possible rescue was held to be via Mamonster. A heading was driven towards Beaujone with all possible speed, including blasting. The trapped miners heard the rescuers and vice versa. Five days after the accident communication was possible and the rescuers worked in darkness to avoid the risk of a firedamp explosion. By 7pm that evening an opening was made, 511 feet (156 m) of tunnel had been dug by hand in five days. All of the 74 miners in Goffin's part survived and were brought to the surface.[37]

Transport

Air

Liège is served by Liège Airport, located in Bierset, a few kilometres west of the city. It is the principal axis for the delivery of freight and in 2011 was the world's 33rd busiest cargo airport.[38]

Maritime

The Port of Liège, located on the River Meuse, is the 3rd largest river port in Europe. Liège also has direct links to Antwerp and Rotterdam via its canals.

Rail

Liège is served by many direct rail links with the rest of Western Europe. Its three principal stations are Liège-Guillemins railway station, Liège-Carré, and Liège-Saint-Lambert. The InterCity Express and Thalys call at Liège-Guillemins, providing direct connections to Cologne and Frankfurt and Paris-Nord respectively.

Liège was once home to a network of trams. However, they were removed by 1967 in favour of the construction of a new metro system. A prototype of the metro was built and a tunnel was dug underneath the city, but the metro was never built. The construction of a new modern tramway has been ordered and is currently scheduled to be open by 2017.

Road

Liège sits at the crossroads of a number of highways including the European route E25, the European Route E42, the European Route E40 and the European Route E313.

Famous inhabitants

Statue of Charlemagne in the centre of Liège

Alger of Liège (11th century), learned priest

Nicolas Ancion (born 1971), writer

Jacques Arcadelt (16th century), composer

Nacer Chadli (born 1989), football player

Charlemagne (birth in Liège uncertain, 8th century), King of the Franks, then crowned emperor

Johannes Ciconia (14th century), composer, Master of the Ars Nova

Jean d'Outremeuse (14th century), writer and historian

Theodor de Bry (1528–1598), engraver

Louis De Geer (1587–1652), introducer of Walloon blast furnaces in Sweden

Gérard de Lairesse (1640–1711), painter

Jean-Maurice Dehousse, politician, Walloon movement activists, first Minister-President of the Walloon Region

Serge Delaive (born 1965), writer

Marie Delcourt (1891–1979), professor at the University, expert of the ancient Greek religion, Walloon movement activist

Louis Dewis (1872–1946), pseudonym for the Post-Impressionist painter born Louis Dewachter, leading retailer who managed the first chain department stores

Emile Digneffe (1858–1937), lawyer and politician

José Dupuis (1833–1900), creator of many roles in Offenbach's opéras-bouffes

Ermano Fegatilli (born 1984), boxer

César Franck (1822–1890), composer

Hubert Joseph Walther Frère-Orban (1812–1896), statesman

Marie Gillain (born 1975), international actress

Anton Gosswin (16th century), composer

Zénobe Gramme (1826–1901), inventor

André Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741–1813), composer

Groupe µ, team of scientists

Gary Hartstein, M.D. (born 1955), Formula 1 delegate- Richard Heintz (1871–1929), Post-Impressionist painter

Justine Henin (born 1982), top ranked female tennis player

Axel Hervelle (born 1983), basketball player

Georges Ista (1874–1939), writer

Joseph Jongen (1873–1953), organist, composer, and educator

Sandra Kim (born 1972), winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 1986 for Belgium

Caroline Lamarche (born 1955), French-speaking writer

Philippe Léonard (born 1974), football player

Linus of Liège (1595–1675), Counter-reformation critic of Isaac Newton

Lambert Lombard (1505–1566), painter

Charles Magnette (1863–1937), lawyer and politician

Georges Malempré (1944), retired UNESCO official

Georges Nagelmackers (1845–1905), founder of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits

Hubert Naich (16th century), composer

Jacques Ochs (1883–1971), artist and Olympic fencing champion

Pippin the Younger (in French: Pépin le Bref; born in Jupille, 8th century), King of the Franks

Henri Pousseur (1929–2009), composer

Jean Rey (1902–1983), Old Minister, Walloon movement activist second President of the European Commission

Gustave Serrurier-Bovy (1858–1910), architect and furniture designer

Georges Simenon (1903–1989), novelist

Stanislas-André Steeman (1908–1970), writer

Violetta Villas (1938–2011), Polish singer and actress

William of St-Thierry (11th century), theologian and mystic

Axel Witsel (born 1989), football player

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858–1931), composer and violinist

Haroun Tazieff (1914–1998), volcanologist and geologist

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Liège is twinned with:

Aachen, Germany[39]

Aachen, Germany[39]

Baton Rouge, United States[40]

Baton Rouge, United States[40]

Cologne, Germany

Cologne, Germany

Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

Lille, France[41]

Lille, France[41]

Kraków, Poland

Kraków, Poland

Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Maastricht, the Netherlands

Maastricht, the Netherlands

Nancy, France

Nancy, France

Plzeň, Czech Republic

Plzeň, Czech Republic

Porto, Portugal[42]

Porto, Portugal[42]

Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Saint-Louis, Senegal

Saint-Louis, Senegal

Szeged, Hungary

Szeged, Hungary

Tangier, Morocco

Tangier, Morocco

Turin, Italy[43]

Turin, Italy[43]

Volgograd, Russia

Volgograd, Russia

See also

- University of Liège

- Liège Science Park

- Bishop of Liège

- Liège–Bastogne–Liège

- Ratherius

Liège Island, Antarctica, named after the city

References

- Notes

^ Population per municipality as of 1 January 2017 (XLS; 397 KB)

^ Statistics Belgium; Population de droit par commune au 1 janvier 2008 (excel-file) Archived 26 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Population of all municipalities in Belgium on 1 January 2008. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

^ ab Statistics Belgium; De Belgische Stadsgewesten 2001 (pdf-file) Archived 29 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Definitions of metropolitan areas in Belgium. The metropolitan area of Liège is divided into three levels. First, the central agglomeration (agglomeratie) with 480,513 inhabitants (2008-01-01). Adding the closest surroundings (banlieue) gives a total of 641,591. And, including the outer commuter zone (forensenwoonzone) the population is 810,983. Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

^ "Ludike – Vroegmiddelnederlands woordenboek" (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 July 2012..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ The Book Collector. Vol. 8 (1959), p. 10.

^ Room, Adrian. 2006. Placenames of the World. 2nd ed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., p. 219.

^ "Liège". 1991. Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Vol. 7. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, p. 344.

^ "D'où vient " Cité Ardente ", le surnom de la ville de Liège". La France en Belgique (in French). Embassy of France. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

^ Brown, Jennifer N. Three women of Liège : a critical edition of and commentary on the Middle English lives of Elizabeth of Spalbeek, Christina Mirabilis and Marie d'Oignies. Turnhout: Brepols, 2008.

^ Henri Pirenne, Belgian Democracy, Its Early History, Translated by J.V. Saunders, The University press, Hull 1915, pp. 140–141. Available online:

Belgian Democracy, Its Early History pp. 72–73.

^ Helfferich, Tryntje, The Thirty Years War: A Documentary History (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 292.

^ "The New York Times, Published 25 March 1886" (PDF). nytimes.com. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

^ See The New York Times, published 23 March 1886

^ Merriam, Ray (2017-03-06). World War 2 in Review: A Primer. ISBN 9781365797620.

^ Erik Jones, Economic Adjustment and Political Transformation in Small States,Oxford Press, 2008, p. 121 978-0-19-920833-3

^ Political History of Belgium: From 1830 Onwards, Academic and Scientific Publishers, Brussels, 2009, p. 278.

ISBN 978-90-5487-517-8

^ "Belgian grenade attack leaves 4 dead, 123 injured". CBC News. 14 December 2011.

^ "Liege shooting: Two police officers and civilian dead in Belgium". BBC News. 29 May 2018.

^ "Klimaatstatistieken van de Belgische gemeenten" (PDF) (in Dutch). Royal Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

^ "Montagne de Bueren".

^ "La ville autour du Piéton".

^ "RTBF Liège: le piétonnier de la rue de la Casquette sera inauguré vendredi".

^ Libre.be, La. "15 août: Outremeuse, où le cœur bat" (in French). Retrieved 2017-07-17.

^ "Photographies - Folklore étudiant". www.ulg.ac.be. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

^ lameuse.be. "Saint-Nicolas: un étudiant qui collecte gagne 15€ par heure". lameuse (in French). Retrieved 2017-03-31.

^ Delandshere, Ludovic Evrard (MyPixhell.com), Pascal Duc+ (Ditc.be), Frank. "Today in Liege - La collecte de Saint-Nicolas des étudiants en médecine ira à la Croix-Rouge". www.todayinliege.be. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

^ Paull, Jennifer (2004-01-01). Fodor's Belgium. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 232. ISBN 9781400013333.

^ "Spring Classics: How to win cycling's hardest one-day races". BBC Sport. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

^ Wynn, Nigel (29 October 2010). "2012 Tour to start in Liege". Cycling Weekly. Time Inc. UK. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

^ Liggett, Phil; Raia, James; Lewis, Sammarye (2005). Tour de France for Dummies. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7645-8449-7.

^ "Details of 2012 Tour de France start official". Cyclingnews.com. Immediate Media Company. 18 November 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

^ MacMichael, Simon (20 November 2010). "Details of 2012 Tour de France Grand Depart announced". road.cc. Farrelly Atkinson. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

^ "Web Oficial de la Vuelta a Espańa 2009 – Official Web Site Vuelta a Espańa 2009". Lavuelta.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

^ "Sunday, July 2nd - Stage 2 - 206km". letour.fr. ASO. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

^ Fightnews (2011-2-26) Fegatilli takes Foster's Euro belt Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Fightnews.com. Retrieved 2011-3-31

^ NASA – A Nighttime View of Liège, Belgium. Nasa.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

^ Thomson, Thomas (April 1816), "Account of an Accident which happened in a Coal-Mine at Liège in 1812", Annals of Philosophy, London: Robert Baldwin, VII (XL), pp 260 – 263, retrieved 28 December 2014

^ McCurry, John. "The world's top 50 airports". Air Cargo News. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013.

^ "Aachen [Germany]". liege.be. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

^ Angie Francalancia (23 September 1985). "CODOFIL welcomes Prince Philippe". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. B, p. 1).

^ "Lille Facts & Figures". Mairie-Lille.fr. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

^ "International Relations of the City of Porto" (PDF). 2006–2009 Municipal Directorate of the Presidency Services International Relations Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

^ Pessotto, Lorenzo. "International Affairs – Twinnings and Agreements". International Affairs Service in cooperation with Servizio Telematico Pubblico. City of Torino. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liège. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Liège. |

- Official website of the city of Liège

- Liège congres

- Leodium: the touristic and cultural network

- Coat of arms of Liège