Room and pillar mining

Room and pillar (variant of breast stoping), also called pillar and stall,[1] is a mining system in which the mined material is extracted across a horizontal plane, creating horizontal arrays of rooms and pillars. The ore is extracted in two phases. In the first, "pillars" of untouched material are left to support the roof overburden, and open areas or "rooms" are extracted underground; the pillars are then partially extracted in the same manner as in the "Bord & Pillar method". The technique is usually used for relatively flat-lying deposits, such as those that follow a particular stratum.

The room and pillar system is used in mining coal, iron and base metals ores, particularly when found as manto or blanket deposits, stone and aggregates, talc, soda ash and potash.

[2]

The key to successful room and pillar mining is in the selection of the optimum pillar size. In general practice, the size of both room and pillars are kept almost equal, while in Bord & Pillar, pillar size is much larger than bord (gallery). If the pillars are too small the mine will collapse, but if they are too large, significant quantities of valuable material will be left behind, reducing the profitability of the mine.[2] The percentage of material mined varies depending on many factors, including the material mined, height of the pillar, and roof conditions; typical values are: stone and aggregates 75 percent, coal 60 percent, and potash 50 percent.[2]

Contents

1 History

2 Mine layout

3 Retreat mining

4 See also

5 References

History

A Maryland coal mine from 1850

Room and pillar mining is one of the oldest mining methods. Early room and pillar mines were developed more or less at random, with pillar sizes determined empirically and headings driven in whichever direction was convenient.[3]

Random mine layout makes ventilation planning difficult, and if the pillars are too small, there is the risk of pillar failure. In coal mines, pillar failures are known as squeezes because the roof squeezes down, crushing the pillars. Once one pillar fails, the weight on the adjacent pillars increases, and the result is a chain reaction of pillar failures. Once started, such chain reactions can be extremely difficult to stop, even if they spread slowly.[4]

Mine layout

Room and pillar mines are developed on a grid basis except where geological features such as faults require the regular pattern to be modified. The size of the pillars is determined by calculation. The load-bearing capacity of the material above and below the material being mined and the capacity of the mined material will determine the pillar size.[2]

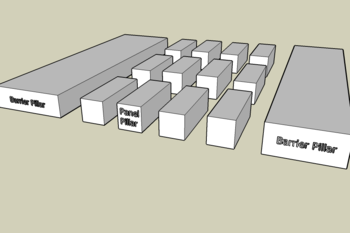

If one pillar fails and surrounding pillars are unable to support the area previously supported by the failed pillar, they may in turn fail. This could lead to the collapse of the whole mine. To prevent this from happening, the mine is divided up into areas or panels.[2] Pillars known as barrier pillars separate the panels. The barrier pillars are significantly larger than the "panel" pillars and are sized to allow them to support a significant part of the panel and prevent progressive collapse of the mine in the event of failure of the panel pillars.[2]

Retreat mining

Retreat mining is often the final stage of room and pillar mining. Once a deposit has been exhausted using this method, the pillars that were left behind initially are removed, or "pulled", retreating back towards the mine's entrance. After the pillars are removed, the roof (or back) is allowed to collapse behind the mining area. Pillar removal must occur in a very precise order to reduce the risks to workers, owing to the high stresses placed on the remaining pillars by the abutment stresses of the caving ground.

Retreat mining is a particularly dangerous form of mining. According to the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), pillar recovery mining has been historically responsible for 25% of American coal mining deaths caused by failures of the roof or walls, even though it represents only 10% of the coal mining industry.[5]

See also

- Longwall mining

References

Notes

^ Mullineux (1973), p. 50.

^ abcdef Hustrulid & Bullock (2001), pp. 493–4.

^ C. M. Young, Percentage of Extraction on of Bituminous Coal with Special Reference to Illinois Conditions, Engineering Experiment Station Bulletin No. 100, University of Illinois, page 130.

^ S. O. Andros, Coal Mining in Illinois, Illinois Coal Mining Investigations, Bulletin 13, Vol II, No 1, University of Illinois, September 1915.

^ Mark, Chris (2010). "Deep Cover Pillar Recovery in the US" (PDF). Retrieved 13 July 2012..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bibliography

Hustrulid, William A.; Bullock, Richard L. (2001). Underground Mining Methods: Engineering Fundamentals and International Case Studies. Society of Mining Engineers. ISBN 978-0-87335-193-5.

Mullineux, F. (1973). "Coal Mining in Lancashire". In Smith, J. H. The Great Human Exploit. Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-0-85033-108-0.