Pantodonta

| Pantodonta Temporal range: Paleocene - Eocene, 63–34 Ma PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

| |

Barylambda | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Eutheria |

| Order: | †Cimolesta |

| Suborder: | †Pantodonta Cope 1873 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Pantodonta is an extinct suborder (or, according to some, an order) of eutherian mammals. These herbivorous mammals were one of the first groups of large mammals to evolve after the end of the Cretaceous.

Pantodonta include some of the largest mammals of their time, but were a diversified group, with some primitive members weighing less than 10 kg (22 lb) and the largest more than 500 kg (1,100 lb).[1]

The earliest and most primitive pantodonts, Bemalambda (with a 20 cm (7.9 in) skull probably the size of a dog) and Hypsilolambda, appear in the early Paleocene Shanghuan Formation in China. All more derived families are collectively classified as Eupantodonta. The pantodonts appear in North America in the middle Paleocene, where Coryphodon survived into the middle Eocene. Pantodont teeth have been found in South America (Alcidedorbignya) and Antarctica,[2] and footprints in a coal mine on Svalbard.[3]

Contents

1 Description

1.1 Dentition

1.2 Postcranial skeleton

2 Classification

3 Timeline of genera

4 References

5 Footnotes

6 External links

Description

Undescribed specimen

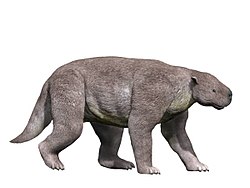

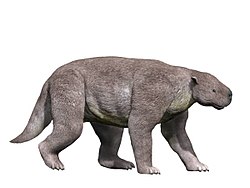

The pantodonts varied considerably in size: the small Archaeolambda, of which there is a complete skeleton from the Late Palaeocene of China, was probably arboreal, while the North American, ground sloth-like Barylambda was massive, slow-moving ("graviportal") and probably browsed on high vegetation.[2]

Dentition

The pantodonts have a primitive dental formula (3.1.4.33.1.4.3) with little or no diastemata. Their most important synapomorphy are the zalambdodont (V-shaped ectoloph opening towards lip) P3–4 and (except in the most primitive families) dilambdodont (W-shaped ectoloph) upper molars. Most pantodonts lacked a hypocone (fourth cusp) and had small conules (additional small cusps). The incisors are small but the canines large, occasionally sabertooth-like. On P3-M3 there is normally an ectoflexus (indentation on the outer side). Asian families can typically be distinguished from the American because their paracone and metacone (bottom of W on side of tongue) tend to be closer together.[1]

The cheek teeth in the lower jaw are also dilambdodont, with broad, high metalophids (posterior crest) and tall metaconid (posterior-interior cusp) with much lower paracristids and small paraconids.[1]

Postcranial skeleton

Pantodonts have plesiomorphic (unaltered) and robust postcranial skeletons. Their five-toed feet are often hoofed with the tarsals similar to those of ungulates, which feature had led to previously suggested ties to arctocyonid "condylarths", but this similarity is now considered primitive.[1]

Classification

The pantodonts were previously grouped with the ungulates as amblypods, paenungulates, or arctocyonids, but since McKenna & Bell 1997 they have been allied with the tillodonts and considered to be derived from the cimolestids. The interrelationship within Pantodonta is controversial,[2] but, following McKenna & Bell 1997, contain about two dozen genera in ten families. Most of the families are known from the Paleocene of either Asia or North America. The pantolambdodontids and coryphodontids survived into the Eocene and the latter are known from across the northern hemisphere.[1] Some dental features can possibly link the most primitve pantodonts to the palaeoryctids, a group of small and insectivorous mammals that evolved during the Cretaceous.[2] Recently a close relationship with Periptychidae has been suggested.[4] This would make pantodonts crown-group ungulate placentals and not related to cimolestids at all.

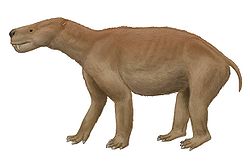

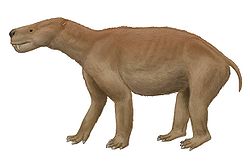

Genera from North America tended to be large and robust, starting with Pantolambda and Caenolambda in the Middle Paleocene epoch, and later in the epoch started to get larger, with Barylambda as the largest Paleocene form of pantodont. However, Asian forms, such as Archaeolambda, tended to be thinner and less robust, around the size of a medium-sized dog. Only later in the Eocene, with Hypercoryphodon, did Asian pantodonts get large and robust.

Life reconstruction of Barylambda faberi

Life reconstruction of Pantolambda bathmodon

Restoration of Titanoides primaevus

Timeline of genera

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Cope, Edward Drinker (1873). "On the short footed Ungulata of the Eocene of Wyoming". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 13: 38–74. Retrieved 1 July 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Kemp, Tom S. (2005). The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198507611. OCLC 56652579.

McKenna, Malcolm C.; Bell, Susan K. (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231110136. OCLC 37345734.

Rose, Kenneth David (2006). The beginning of the age of mammals. Baltimore: JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801884726.

"†PANTODONTA - pantodonts". After McKenna & Bell (1997), and Alroy (2002). Retrieved 3 November 2013.

Footnotes

^ abcde Rose 2006, p. 114

^ abcd Kemp 2005, pp. 238–40

^ "Fossil Arctic animal tracks point to climate risks". Reuters. April 25, 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

^ Halliday, Thomas J.D.; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (February 2017). "Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals". Biological Reviews. 92 (1): 521–55–. doi:10.1111/brv.12242. PMID 28075073.

External links

- Paleocene-Mammals