Torque

| Torque | |

|---|---|

Relationship between force F, torque τ, linear momentum p, and angular momentum L in a system which has rotation constrained to only one plane (forces and moments due to gravity and friction not considered). | |

Common symbols | τ{displaystyle tau }  , M , M |

| SI unit | N⋅m |

Other units | pound-force-feet, lbf⋅inch, ozf⋅in |

| In SI base units | kg⋅m2⋅s−2 |

| Dimension | M L2T−2 |

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

F→=ma→{displaystyle {vec {F}}=m{vec {a}}}  Second law of motion |

|

Branches

|

Fundamentals

|

Formulations

|

Core topics

|

Rotation

|

Scientists

|

Torque, moment, or moment of force is the rotational equivalent of linear force.[1] The concept originated with the studies of Archimedes on the usage of levers. Just as a linear force is a push or a pull, a torque can be thought of as a twist to an object. The symbol for torque is typically τ{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}}

In three dimensions, the torque is a pseudovector; for point particles, it is given by the cross product of the position vector (distance vector) and the force vector. The magnitude of torque of a rigid body depends on three quantities: the force applied, the lever arm vector[2] connecting the origin to the point of force application, and the angle between the force and lever arm vectors. In symbols:

- τ=r×F{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}=mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} ,!}

- τ=‖r‖‖F‖sinθ{displaystyle tau =|mathbf {r} |,|mathbf {F} |sin theta ,!}

where

τ{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}}is the torque vector and τ{displaystyle tau }

is the magnitude of the torque,

r is the position vector (a vector from the origin of the coordinate system defined to the point where the force is applied)

F is the force vector,- × denotes the cross product, which is defined as magnitudes of the respective vectors times sinθ{displaystyle sin theta }

.

θ{displaystyle theta }is the angle between the force vector and the lever arm vector.

The SI unit for torque is N⋅m. For more on the units of torque, see Units.

Contents

1 Defining terminology

2 Definition and relation to angular momentum

2.1 Proof of the equivalence of definitions

3 Units

4 Special cases and other facts

4.1 Moment arm formula

4.2 Static equilibrium

4.3 Net force versus torque

5 Machine torque

6 Relationship between torque, power, and energy

6.1 Proof

6.2 Conversion to other units

6.3 Derivation

7 Principle of moments

8 Torque multiplier

9 See also

10 References

11 External links

Defining terminology

The term torque was introduced into English scientific literature by James Thomson, the brother of Lord Kelvin, in 1884.[3] However, torque is referred to using different vocabulary depending on geographical location and field of study. This article refers to the definition used in US physics in its usage of the word torque.[4] In the UK and in US mechanical engineering, torque is referred to as moment of force, usually shortened to moment.[5] In US physics[4] and UK physics terminology these terms are interchangeable, unlike in US mechanical engineering, where the term torque is used for the closely related "resultant moment of a couple".[5]

Torque is defined mathematically as the rate of change of angular momentum of an object. The definition of torque states that one or both of the angular velocity or the moment of inertia of an object are changing. Moment is the general term used for the tendency of one or more applied forces to rotate an object about an axis, but not necessarily to change the angular momentum of the object (the concept which is called torque in physics).[5] For example, a rotational force applied to a shaft causing acceleration, such as a drill bit accelerating from rest, results in a moment called a torque. By contrast, a lateral force on a beam produces a moment (called a bending moment), but since the angular momentum of the beam is not changing, this bending moment is not called a torque. Similarly with any force couple on an object that has no change to its angular momentum, such moment is also not called a torque.

This article follows the US physics terminology by calling all moments by the term torque, whether or not they cause the angular momentum of an object to change.

Definition and relation to angular momentum

A particle is located at position r relative to its axis of rotation. When a force F is applied to the particle, only the perpendicular component F⊥ produces a torque. This torque τ = r × F has magnitude τ = |r| |F⊥| = |r| |F| sin θ and is directed outward from the page.

A force applied at a right angle to a lever multiplied by its distance from the lever's fulcrum (the length of the lever arm) is its torque. A force of three newtons applied two metres from the fulcrum, for example, exerts the same torque as a force of one newton applied six metres from the fulcrum. The direction of the torque can be determined by using the right hand grip rule: if the fingers of the right hand are curled from the direction of the lever arm to the direction of the force, then the thumb points in the direction of the torque.[6]

More generally, the torque on a particle (which has the position r in some reference frame) can be defined as the cross product:

- τ=r×F,{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}=mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} ,}

where r is the particle's position vector relative to the fulcrum, and F is the force acting on the particle. The magnitude τ of the torque is given by

- τ=rFsinθ,{displaystyle tau =rFsin theta ,!}

where r is the distance from the axis of rotation to the particle, F is the magnitude of the force applied, and θ is the angle between the position and force vectors. Alternatively,

- τ=rF⊥,{displaystyle tau =rF_{perp },}

where F⊥ is the amount of force directed perpendicularly to the position of the particle. Any force directed parallel to the particle's position vector does not produce a torque.[7][8]

It follows from the properties of the cross product that the torque vector is perpendicular to both the position and force vectors. The torque vector points along the axis of the rotation that the force vector (starting from rest) would initiate. The resulting torque vector direction is determined by the right-hand rule.[7]

The unbalanced torque on a body along axis of rotation determines the rate of change of the body's angular momentum,

- τ=dLdt{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}={frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}}

where L is the angular momentum vector and t is time. If multiple torques are acting on the body, it is instead the net torque which determines the rate of change of the angular momentum:

- τ1+⋯+τn=τnet=dLdt.{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}_{1}+cdots +{boldsymbol {tau }}_{n}={boldsymbol {tau }}_{mathrm {net} }={frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}.}

For the motion of a point particle,

- L=Iω,{displaystyle mathbf {L} =I{boldsymbol {omega }},}

where I is the moment of inertia and ω is the angular velocity. It follows that

- τnet=dLdt=d(Iω)dt=Idωdt+dIdtω=Iα+d(mr2)dtω=Iα+2rp||ω,{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}_{mathrm {net} }={frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}={frac {mathrm {d} (I{boldsymbol {omega }})}{mathrm {d} t}}=I{frac {mathrm {d} {boldsymbol {omega }}}{mathrm {d} t}}+{frac {mathrm {d} I}{mathrm {d} t}}{boldsymbol {omega }}=I{boldsymbol {alpha }}+{frac {mathrm {d} (mr^{2})}{mathrm {d} t}}{boldsymbol {omega }}=I{boldsymbol {alpha }}+2rp_{||}{boldsymbol {omega }},}

where α is the angular acceleration of the particle, and p|| is the radial component of its linear momentum. This equation is the rotational analogue of Newton's Second Law for point particles, and is valid for any type of trajectory. Note that although force and acceleration are always parallel and directly proportional, the torque τ need not be parallel or directly proportional to the angular acceleration α. This arises from the fact that although mass is always conserved, the moment of inertia in general is not.

Proof of the equivalence of definitions

The definition of angular momentum for a single particle is:

- L=r×p{displaystyle mathbf {L} =mathbf {r} times {boldsymbol {p}}}

where "×" indicates the vector cross product, p is the particle's linear momentum, and r is the displacement vector from the origin (the origin is assumed to be a fixed location anywhere in space). The time-derivative of this is:

- dLdt=r×dpdt+drdt×p.{displaystyle {frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}=mathbf {r} times {frac {mathrm {d} {boldsymbol {p}}}{mathrm {d} t}}+{frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {r} }{mathrm {d} t}}times {boldsymbol {p}}.}

This result can easily be proven by splitting the vectors into components and applying the product rule. Now using the definition of force F=dpdt{displaystyle mathbf {F} ={frac {mathrm {d} {boldsymbol {p}}}{mathrm {d} t}}}

- dLdt=r×F+v×p.{displaystyle {frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}=mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} +mathbf {v} times {boldsymbol {p}}.}

The cross product of momentum p{displaystyle {boldsymbol {p}}}

By definition, torque τ = r × F. Therefore, torque on a particle is equal to the

first derivative of its angular momentum with respect to time.

If multiple forces are applied, Newton's second law instead reads Fnet = ma, and it follows that

- dLdt=r×Fnet=τnet.{displaystyle {frac {mathrm {d} mathbf {L} }{mathrm {d} t}}=mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} _{mathrm {net} }={boldsymbol {tau }}_{mathrm {net} }.}

This is a general proof.

Units

Torque has dimension force times distance, symbolically L2MT−2. Official SI literature suggests using the unit newton metre (N⋅m) or the unit joule per radian.[9] The unit newton metre is properly denoted N⋅m or N m.[10] This avoids ambiguity with mN, millinewtons.

The SI unit for energy or work is the joule. It is dimensionally equivalent to a force of one newton acting over a distance of one metre, but it is not used for torque. Energy and torque are entirely different concepts, so the practice of using different unit names (i.e., reserving newton metres for torque and using only joules for energy) helps avoid mistakes and misunderstandings.[9] The dimensional equivalence of these units is not simply a coincidence: a torque of 1 N⋅m applied through a full revolution will require an energy of exactly 2π joules. Mathematically,

- E=τθ {displaystyle E=tau theta }

where E is the energy, τ is magnitude of the torque, and θ is the angle moved (in radians). This equation motivates the alternate unit name joules per radian.[9]

In Imperial units, "pound-force-feet" (lbf⋅ft), "foot-pounds-force", "inch-pounds-force", "ounce-force-inches" (ozf⋅in)[citation needed] are used, and other non-SI units of torque includes "metre-kilograms-force". For all these units, the word "force" is often left out.[11] For example, abbreviating "pound-force-foot" to simply "pound-foot" (in this case, it would be implicit that the "pound" is pound-force and not pound-mass). This is an example of the confusion caused by the use of English units that may be avoided with SI units because of the careful distinction in SI between force (in newtons) and mass (in kilograms).

Torque is sometimes listed with units that do not make dimensional sense, such as the gram-centimeter. In this case, "gram" should be understood as the force given by the weight of 1 gram on the surface of the Earth (i.e. 0.00980665 N). The surface of the Earth has a standard gravitational field strength of 9.80665 N/kg.

Special cases and other facts

Moment arm formula

Moment arm diagram

A very useful special case, often given as the definition of torque in fields other than physics, is as follows:

- τ=(moment arm)(force).{displaystyle tau =({text{moment arm}})({text{force}}).}

The construction of the "moment arm" is shown in the figure to the right, along with the vectors r and F mentioned above. The problem with this definition is that it does not give the direction of the torque but only the magnitude, and hence it is difficult to use in three-dimensional cases. If the force is perpendicular to the displacement vector r, the moment arm will be equal to the distance to the centre, and torque will be a maximum for the given force. The equation for the magnitude of a torque, arising from a perpendicular force:

- τ=(distance to centre)(force).{displaystyle tau =({text{distance to centre}})({text{force}}).}

For example, if a person places a force of 10 N at the terminal end of a wrench that is 0.5 m long (or a force of 10 N exactly 0.5 m from the twist point of a wrench of any length), the torque will be 5 N⋅m – assuming that the person moves the wrench by applying force in the plane of movement and perpendicular to the wrench.

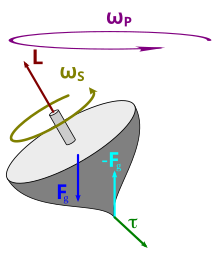

The torque caused by the two opposing forces Fg and −Fg causes a change in the angular momentum L in the direction of that torque. This causes the top to precess.

Static equilibrium

For an object to be in static equilibrium, not only must the sum of the forces be zero, but also the sum of the torques (moments) about any point. For a two-dimensional situation with horizontal and vertical forces, the sum of the forces requirement is two equations: ΣH = 0 and ΣV = 0, and the torque a third equation: Στ = 0. That is, to solve statically determinate equilibrium problems in two-dimensions, three equations are used.

Net force versus torque

When the net force on the system is zero, the torque measured from any point in space is the same. For example, the torque on a current-carrying loop in a uniform magnetic field is the same regardless of your point of reference. If the net force F{displaystyle mathbf {F} }

τ2=τ1+(r1−r2)×F{displaystyle {boldsymbol {tau }}_{2}={boldsymbol {tau }}_{1}+(mathbf {r} _{1}-mathbf {r} _{2})times mathbf {F} }

Machine torque

Torque curve of a motorcycle ("BMW K 1200 R 2005"). The horizontal axis shows the speed (in rpm) that the crankshaft is turning, and the vertical axis is the torque (in newton metres) that the engine is capable of providing at that speed.

Torque forms part of the basic specification of an engine: the power output of an engine is expressed as its torque multiplied by its rotational speed of the axis. Internal-combustion engines produce useful torque only over a limited range of rotational speeds (typically from around 1,000–6,000 rpm for a small car). One can measure the varying torque output over that range with a dynamometer, and show it as a torque curve.

Steam engines and electric motors tend to produce maximum torque close to zero rpm, with the torque diminishing as rotational speed rises (due to increasing friction and other constraints). Reciprocating steam-engines and electric motors can start heavy loads from zero rpm without a clutch.

Relationship between torque, power, and energy

If a force is allowed to act through a distance, it is doing mechanical work. Similarly, if torque is allowed to act through a rotational distance, it is doing work. Mathematically, for rotation about a fixed axis through the center of mass,

- W=∫θ1θ2τ dθ,{displaystyle W=int _{theta _{1}}^{theta _{2}}tau mathrm {d} theta ,}

where W is work, τ is torque, and θ1 and θ2 represent (respectively) the initial and final angular positions of the body.[12]

Proof

The work done by a variable force acting over a finite linear displacement s{displaystyle s}

- W=∫s1s2F→⋅ds→{displaystyle W=int _{s_{1}}^{s_{2}}{vec {F}}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {s}}}

However, the infinitesimal linear displacement ds→{displaystyle mathrm {d} {vec {s}}}

- ds→=dθ→×r→{displaystyle mathrm {d} {vec {s}}=mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}times {vec {r}}}

Substitution in the above expression for work gives

- W=∫s1s2F→⋅dθ→×r→{displaystyle W=int _{s_{1}}^{s_{2}}{vec {F}}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}times {vec {r}}}

The expression F→⋅dθ→×r→{displaystyle {vec {F}}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}times {vec {r}}}

![{displaystyle left[{vec {F}},mathrm {d} {vec {theta }},{vec {r}}right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/72ea8287e337fb698bb2ddfb0924b4a3412bc2ee)

- [F→dθ→r→]=r→×F→⋅dθ→{displaystyle left[{vec {F}},mathrm {d} {vec {theta }},{vec {r}}right]={vec {r}}times {vec {F}}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}}

But as per the definition of torque,

- τ→=r→×F→{displaystyle {vec {tau }}={vec {r}}times {vec {F}}}

Corresponding substitution in the expression of work gives,

- W=∫s1s2τ→⋅dθ→{displaystyle W=int _{s_{1}}^{s_{2}}{vec {tau }}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}}

Since the parameter of integration has been changed from linear displacement to angular displacement, the limits of the integration also change correspondingly, giving

- W=∫θ1θ2τ→⋅dθ→{displaystyle W=int _{theta _{1}}^{theta _{2}}{vec {tau }}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}}

If the torque and the angular displacement are in the same direction, then the scalar product reduces to a product of magnitudes; i.e., τ→⋅dθ→=|τ→||dθ→|cos0=τdθ{displaystyle {vec {tau }}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}=left|{vec {tau }}right|left|,mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}right|cos 0=tau ,mathrm {d} theta }

- W=∫θ1θ2τdθ{displaystyle W=int _{theta _{1}}^{theta _{2}}tau ,mathrm {d} theta }

It follows from the work-energy theorem that W also represents the change in the rotational kinetic energy Er of the body, given by

- Er=12Iω2,{displaystyle E_{mathrm {r} }={tfrac {1}{2}}Iomega ^{2},}

where I is the moment of inertia of the body and ω is its angular speed.[12]

Power is the work per unit time, given by

- P=τ⋅ω,{displaystyle P={boldsymbol {tau }}cdot {boldsymbol {omega }},}

where P is power, τ is torque, ω is the angular velocity, and ⋅ represents the scalar product.

Algebraically, the equation may be rearranged to compute torque for a given angular speed and power output. Note that the power injected by the torque depends only on the instantaneous angular speed – not on whether the angular speed increases, decreases, or remains constant while the torque is being applied (this is equivalent to the linear case where the power injected by a force depends only on the instantaneous speed – not on the resulting acceleration, if any).

In practice, this relationship can be observed in bicycles: Bicycles are typically composed of two road wheels, front and rear gears (referred to as sprockets) meshing with a circular chain, and a derailleur mechanism if the bicycle's transmission system allows multiple gear ratios to be used (i.e. multi-speed bicycle), all of which attached to the frame. A cyclist, the person who rides the bicycle, provides the input power by turning pedals, thereby cranking the front sprocket (commonly referred to as chainring). The input power provided by the cyclist is equal to the product of cadence (i.e. the number of pedal revolutions per minute) and the torque on spindle of the bicycle's crankset. The bicycle's drivetrain transmits the input power to the road wheel, which in turn conveys the received power to the road as the output power of the bicycle. Depending on the gear ratio of the bicycle, a (torque, rpm)input pair is converted to a (torque, rpm)output pair. By using a larger rear gear, or by switching to a lower gear in multi-speed bicycles, angular speed of the road wheels is decreased while the torque is increased, product of which (i.e. power) does not change.

Consistent units must be used. For metric SI units, power is watts, torque is newton metres and angular speed is radians per second (not rpm and not revolutions per second).

Also, the unit newton metre is dimensionally equivalent to the joule, which is the unit of energy. However, in the case of torque, the unit is assigned to a vector, whereas for energy, it is assigned to a scalar.

Conversion to other units

A conversion factor may be necessary when using different units of power or torque. For example, if rotational speed (revolutions per time) is used in place of angular speed (radians per time), we multiply by a factor of 2π radians per revolution. In the following formulas, P is power, τ is torque, and ν (Greek letter nu) is rotational speed.

- P=τ⋅2π⋅ν{displaystyle P=tau cdot 2pi cdot nu }

Showing units:

- P(W)=τ(N⋅m)⋅2π(rad/rev)⋅ν(rev/sec){displaystyle P({rm {W}})=tau {rm {(Ncdot m)}}cdot 2pi {rm {(rad/rev)}}cdot nu {rm {(rev/sec)}}}

Dividing by 60 seconds per minute gives us the following.

- P(W)=τ(N⋅m)⋅2π(rad/rev)⋅ν(rpm)60{displaystyle P({rm {W}})={frac {tau {rm {(Ncdot m)}}cdot 2pi {rm {(rad/rev)}}cdot nu {rm {(rpm)}}}{60}}}

where rotational speed is in revolutions per minute (rpm).

Some people (e.g., American automotive engineers) use horsepower (imperial mechanical) for power, foot-pounds (lbf⋅ft) for torque and rpm for rotational speed. This results in the formula changing to:

- P(hp)=τ(lbf⋅ft)⋅2π(rad/rev)⋅ν(rpm)33,000.{displaystyle P({rm {hp}})={frac {tau {rm {(lbfcdot ft)}}cdot 2pi {rm {(rad/rev)}}cdot nu ({rm {rpm}})}{33,000}}.}

The constant below (in foot pounds per minute) changes with the definition of the horsepower; for example, using metric horsepower, it becomes approximately 32,550.

Use of other units (e.g., BTU per hour for power) would require a different custom conversion factor.

Derivation

For a rotating object, the linear distance covered at the circumference of rotation is the product of the radius with the angle covered. That is: linear distance = radius × angular distance. And by definition, linear distance = linear speed × time = radius × angular speed × time.

By the definition of torque: torque = radius × force. We can rearrange this to determine force = torque ÷ radius. These two values can be substituted into the definition of power:

- power=force⋅linear distancetime=(torquer)⋅(r⋅angular speed⋅t)t=torque⋅angular speed.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{text{power}}&={frac {{text{force}}cdot {text{linear distance}}}{text{time}}}\[6pt]&={frac {left({dfrac {text{torque}}{r}}right)cdot (rcdot {text{angular speed}}cdot t)}{t}}\[6pt]&={text{torque}}cdot {text{angular speed}}.end{aligned}}}

The radius r and time t have dropped out of the equation. However, angular speed must be in radians, by the assumed direct relationship between linear speed and angular speed at the beginning of the derivation. If the rotational speed is measured in revolutions per unit of time, the linear speed and distance are increased proportionately by 2π in the above derivation to give:

- power=torque⋅2π⋅rotational speed.{displaystyle {text{power}}={text{torque}}cdot 2pi cdot {text{rotational speed}}.,}

If torque is in newton metres and rotational speed in revolutions per second, the above equation gives power in newton metres per second or watts. If Imperial units are used, and if torque is in pounds-force feet and rotational speed in revolutions per minute, the above equation gives power in foot pounds-force per minute. The horsepower form of the equation is then derived by applying the conversion factor 33,000 ft⋅lbf/min per horsepower:

- power=torque⋅2π⋅rotational speed⋅ft⋅lbfmin⋅horsepower33,000⋅ft⋅lbfmin≈torque⋅RPM5,252{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{text{power}}&={text{torque}}cdot 2pi cdot {text{rotational speed}}cdot {frac {{text{ft}}cdot {text{lbf}}}{text{min}}}cdot {frac {text{horsepower}}{33,000cdot {frac {{text{ft}}cdot {text{lbf}}}{text{min}}}}}\[6pt]&approx {frac {{text{torque}}cdot {text{RPM}}}{5,252}}end{aligned}}}

because 5252.113122≈33,0002π.{displaystyle 5252.113122approx {frac {33,000}{2pi }}.,}

Principle of moments

The Principle of Moments, also known as Varignon's theorem (not to be confused with the geometrical theorem of the same name) states that the sum of torques due to several forces applied to a single point is equal to the torque due to the sum (resultant) of the forces. Mathematically, this follows from:

- (r×F1)+(r×F2)+⋯=r×(F1+F2+⋯).{displaystyle (mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} _{1})+(mathbf {r} times mathbf {F} _{2})+cdots =mathbf {r} times (mathbf {F} _{1}+mathbf {F} _{2}+cdots ).}

Torque multiplier

Torque can be multiplied via three methods: by locating the fulcrum such that the length of a lever is increased; by using a longer lever; or by the use of a speed reducing gearset or gear box. Such a mechanism multiplies torque, as rotation rate is reduced.

See also

- Moment

- Conversion of units

- Friction torque

- Mechanical equilibrium

- Rigid body dynamics

- Statics

- Torque converter

- Torque limiter

- Torque screwdriver

- Torque tester

- Torque wrench

- Torsion (mechanics)

References

^ Serway, R. A. and Jewett, Jr. J.W. (2003). Physics for Scientists and Engineers. 6th Ed. Brooks Cole. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

^ Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0809-4.

^ Thomson, James; Larmor, Joseph (1912). Collected Papers in Physics and Engineering. University Press. p. civ., at Google books

^ ab Physics for Engineering by Hendricks, Subramony, and Van Blerk, Chinappi page 148, Web link

^ abc Kane, T.R. Kane and D.A. Levinson (1985). Dynamics, Theory and Applications pp. 90–99: Free download

^ "Right Hand Rule for Torque". Retrieved 2007-09-08.

^ ab Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert (1970). Fundamentals of Physics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 184–85.

^ Knight, Randall; Jones, Brian; Field, Stuart (2016). College Physics: A Strategic Approach. Jones, Brian, 1960-, Field, Stuart, 1958- (Third edition, technology update ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 199. ISBN 9780134143323. OCLC 922464227.

^ abc From the official SI website: "...For example, the quantity torque may be thought of as the cross product of force and distance, suggesting the unit newton metre, or it may be thought of as energy per angle, suggesting the unit joule per radian."

^ "SI brochure Ed. 8, Section 5.1". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 2014. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

^ See, for example: "CNC Cookbook: Dictionary: N-Code to PWM". Retrieved 2008-12-17.

^ ab Kleppner, Daniel; Kolenkow, Robert (1973). An Introduction to Mechanics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 267–68.

External links

| Look up torque in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Torque. |

"Horsepower and Torque" An article showing how power, torque, and gearing affect a vehicle's performance.

"Torque vs. Horsepower: Yet Another Argument" An automotive perspective

Torque and Angular Momentum in Circular Motion on Project PHYSNET.- An interactive simulation of torque

- Torque Unit Converter

A feel for torque An order-of-magnitude interactive.

![{displaystyle left[{vec {F}},mathrm {d} {vec {theta }},{vec {r}}right]={vec {r}}times {vec {F}}cdot mathrm {d} {vec {theta }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cba9665fa7924628717ae3ee0d34658b239529b6)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{text{power}}&={frac {{text{force}}cdot {text{linear distance}}}{text{time}}}\[6pt]&={frac {left({dfrac {text{torque}}{r}}right)cdot (rcdot {text{angular speed}}cdot t)}{t}}\[6pt]&={text{torque}}cdot {text{angular speed}}.end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4382d186e4085de735546ad46847d852af843fcb)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{text{power}}&={text{torque}}cdot 2pi cdot {text{rotational speed}}cdot {frac {{text{ft}}cdot {text{lbf}}}{text{min}}}cdot {frac {text{horsepower}}{33,000cdot {frac {{text{ft}}cdot {text{lbf}}}{text{min}}}}}\[6pt]&approx {frac {{text{torque}}cdot {text{RPM}}}{5,252}}end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5de129cd918c8164ddc724a5ce9efb6d86fc7208)